Training a Deep-Q Network in Rust To Play Blackjack!

Introduction

Almost everyone knows the game Blackjack (If you don’t, you can read the rules here). It’s a simple, mostly luck-based game, yet there exists a certain amount of strategy to it. For example, if your hand has a sum of 20, you don’t want to hit, since any card other than an ace will make you bust and lose (unless you already have an ace). In this post, we train an agent to learn a good blackjack strategy using a Reinforcement Learning (RL) method known as Deep-Q Learning. After we train the agent, we’ll do some cool experiments with it! All of the code is written from scratch in Rust. We’re going to use a Neural Net library I used to train a Generative Adverserial Network (GAN) to generate digits, so if you haven’t read that one, I suggest you read it first :)

Reinforcement Learning

Modern ML methods are generally split into three groups: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. The former two concern an agent learning from a dataset, whether labeled (supervised learning), or unlabeled (unsupervised learning). Reinforcement Learning, on the other hand, involves an agent acting within an interactive environment.

The best example for an interactive enviornment is a game. Consider, for example, the fighting game Tekken. The state of the game is characteized by the frames currently seen on the screen, which are NxMx3 tensors (we add the 3 since the game uses RGB), where N and M are the dimensions of the screen.

At each timestep, the player (called the agent in RL), has to pick an action: move left, right, kick, punch, etc. These actions transition the game from the previous state to a new state. Players don’t just pick actions randomly: they aim to maximize some reward. For example, the reward can be defined as the score in the game, or the negative of the oppontent’s health (maximizing the negative of the opponent’s health is equivalent to minimizing their health).

This reward r(t) is defined for each timestep t. The function the agent seeks to maximize is the total discounted reward: \

The higher the discount factor gamma is, the more the agent cares about short-term rewards rather than long-term rewards (since gamma will decay slower).

Tekken is complex, but Blackjack is much simpler. The environment is only characterized by three things: \

- The agent’s current hand

- The face-up card of the dealer

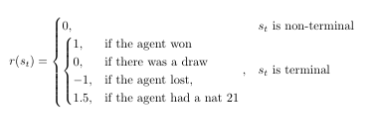

- Whether the agent has an Ace in their hand (aces are special, since they can be counted both as 1s and as 11s) The only possible actions are Hit and Stand (in real Blackjack there’s also double down and split, but I didn’t implement them). Defining the reward function is also easy, and can be summarized as “win good, lose bad”. In more formal terms, we define, at each timestamp:

If the state is non-terminal (i.e. the game hasn’t ended yet), we don’t know the game result yet, so there’s nothing to reward the agent for (in other problems we can reward the agent at each timestep; for example in Tekken the game score changes nearly every timestep).

If the state is terminal (i.e. the game had reached its end), we give the agent +1 if they won, +0 if a draw occurred, and -1 if they lost. We also give the agent +1.5 if they won with a nat 21 (the player’s first two cards are an Ace and a card with value 10, so their hand is 11+10=21). Since the agent’s goal is to maximize its reward, it learns that winning is good, and losing is bad, much like human players.

Let’s write some blackjack code! Note that we need our code to be easy to train an agent on later. We start by defining the state of the game in a struct fittingly named State:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

// The current state of the game. This is what the agent sees

pub struct State {

hand: usize, // The sum of the agent's hand (i.e. if agent has J 5 3, then hand=18)

face_up: usize, // The value of the dealer's face up card

has_ace: bool, // Whether the agent has an ace in their hand. Aces are important since they can be both 11 and 1

}

Note that we don’t actually care what cards the hand is composed of; we only care about the sum (although it would be interesting to implement an agent that knows what cards are in their hand, and see if it learns to do card-counting).

We define the possible actions in an enum:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#[derive(Clone)]

// Possible actions to play. Real blackjack has more actions, such as split and double down

// but we only do hit and stand

pub enum Action {

Hit,

Stand,

}

Then, we define the environment itself:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

// The game environment

pub struct Blackjack {

// The card pack

pack: CardPack,

// Current game state (from the viewpoint of the agent)

state: State,

// Whether the game is over

over: bool,

// Game reward:

// +1 If agent wins

// +0 If draw

// -1 If agent loses

// +1.5 If natural blackjack (i.e. A 10, A J, etc.)

// As long as the game is not finished, this is 0

reward: f32,

// The dealer's hand

dealer_hand: usize,

// Whether we've already "used" the agent's ace

used_ace: bool,

}

The first memeber of the struct is the deck of cards, which is defined in a struct called CardPack. This struct is used to draw from a deck of cards with correct probabilities (i.e. if we drew three sevens, the probability of drawing a seven decreases). It isn’t very interesting, so I didn’t include its code in the post.

The environment also contains the state of the game, a boolean indicating whether the game is over, the reward in the current timestep as we defined earlier, and some other members related to the game itself.

There’s not much to say about the initialization of the game: we simply draw two cards for the agent and two cards for the dealer, and initialize the state accordngly. To execute an action in the game, we use a function method named step, which takes in a mutable reference to the game, and an Action:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

impl Blackjack {

// Perform an action in the game

pub fn step(&mut self, action: &Action) {

match action {

Action::Hit => self.hit(),

Action::Stand => self.stand(),

}

}

}

The hit and stand methods do what they sound like. For example, here’s the implementation of hit:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

impl Blackjack {

...

fn hit(&mut self) {

// Draw a card from the pack

let new_card = self.pack.take_card().unwrap();

let agent_hand = self.state.hand;

// If the agent busts, the game is over and they lose

if agent_hand + new_card > 21 {

// If they player has an ace, go back to treating it as a 1

if self.state.has_ace && !self.used_ace {

self.state.hand += new_card;

self.state.hand -= 10;

// We've already "used the ace"

self.used_ace = true;

return;

}

self.over = true;

self.reward = -1f32;

return;

}

// Otherwise, the card is added to their hand

self.state.hand += new_card;

// If the card is an ace, mark it

if new_card == 1 {

self.state.has_ace = true;

}

}

...

}

We also define a function reset that resets the state of the environment. This function will come in handy later when training the agent:

1

2

3

4

5

6

impl Blackjack {

// Reset the game

pub fn reset(&mut self) {

*self = Blackjack::new();

}

}

That’s it for the implementation of Blackjack! Let’s do a test run and write a short interactive blackjack program:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

use std::io::stdin;

use rustdqn::blackjack;

fn main() {

println!("Alrighty, let's play some blackjack!");

let mut game = blackjack::Blackjack::new();

while !game.is_over() {

println!("Game state: {:?}");

let mut buf = String::new();

println!("Pick an action: ");

println!("1 - Hit\n2 - Stand");

print!("> ");

stdin().read_line(&mut buf).unwrap();

let choice = buf.chars().nth(0).unwrap();

match choice {

'1' => game.step(&blackjack::Action::Hit),

'2' => game.step(&blackjack::Action::Stand),

_ => println!("Unknown action!"),

}

}

println!("Game is over, your reward is: {}", game.reward());

}

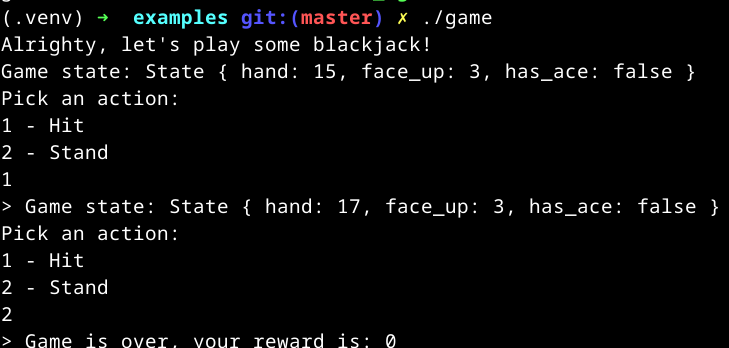

A test run:

In this example, I started with a hand of 15, then hit and drew a 2. I then stood, and got a draw (reward 0). Now that we have a functional implementation, in the next section we’ll see how to train an agent on it!

Deep-Q Learning

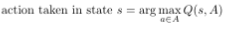

There are many methods to train RL agents, but the one we use in this post, which is also one of the most popular ones, is called Q-Learning, which revolves around a function called the “Q function”. Suppose you had a function, Q, that takes in a state s and an action a, and tells you the expected reward you can get if your execute action a in state s. Given this function Q, deriving an optimal policy is trivial: if the agent is currently in state s, it applies the action a such that Q(s, a) is maximal, i.e. the action that maximizes the expected reward. In other words:

where A is the set of possible actions. The only problem is how to find this Q function. Going back to the Tekken example, directly calculating Q would entail going through each possible state-action pair, and calculating the expected reward, which is infeasible for sufficiently large environments. Instead, we resort to approximating Q. When this is done using Deep Neural Networks, this is called Deep-Q Learning (DQL). The network that is used to approximate Q is called a Deep-Q Network (DQN).

Note that instead of having our network take in the state and a certain action, and predict the Q value for that action, we’ll have the network take in only a state, and predict the Q-values for all possible actions.

So how do we train a DQN? Usually, when approximating an unkown function, we use the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function, and to do that we need two things:

- The predictions of our network on some inputs x_1, …, x_N

- The output of the unknown function on x_1, …, x_N To get 1, at each training step, we let our agent play a game of blackjack (a full game is called an episode), and store all transitions (transitions are 4-tuples composed of the current state s_t, an action a, the next state s_{t + 1} after executing action a at state s_t, and the reward the agent got for doing so) that occur in a replay buffer, which is a data structure whose job is to record past transitions.

Given this data structure, we can then sample a random batch of transitions from it and run the DQN on their states. Remember that the DQN outputs Q-values for all actions, so we need to select the one corresponding to the action actually taken in the transition. The replay buffer is a data structure (for example a deque) whose job is to record all transitions that occur. To implement this, we define aReplayMemorystructure that holds a deque of transitions:

1

2

3

4

// The replay buffer of the DQN

pub struct ReplayMemory {

memory: VecDeque<Transition>,

}

Each transition is defined as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// A transition from state s_1 with action a to state s_2 and reward r

pub struct Transition {

state: State,

action: Action,

next_state: Option<State>,

reward: f32,

}

Then, to store a transition in the replay buffer we simply push it to the back of the deque:

1

2

3

4

// Store a transition in the ReplayMemory

pub fn store(&mut self, transition: Transition) {

self.memory.push_back(transition);

}

And to sample a batch of transitions, we use

1

2

3

4

5

6

// Sample a batch of transitions from the memory

pub fn sample(&self, batch_size: usize) -> Vec<&Transition> {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

self.memory.iter().choose_multiple(&mut rng, batch_size)

}

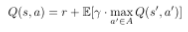

Getting 2 is more complicated, since we don’t have access to the Q function! Instead, we use the fact that the Q function obeys an important identity, known as the Bellman equation (named after Richard E. Bellman):

This equation is saying that the expected reward for executing action a in state s, is equal to the reward gained at the current timestamp (i.e. after executing action a), plus the discounted expected reward we get for playing optimally from then on (s’ is the state we transition to after executing action a).

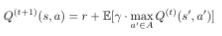

The Bellman equation can be used as an iterative update to approximate Q: Let Q^{(t)} be our current approximation. Then at each iteration, we change our approximation as follows:

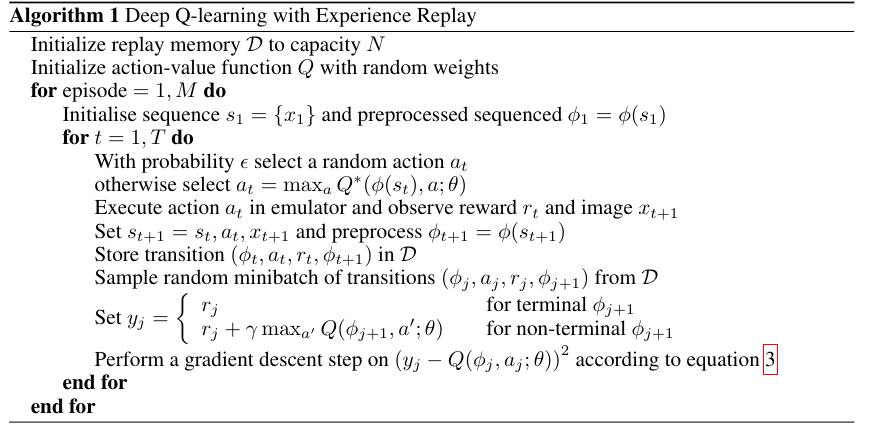

we apply this update on the current approximation of Q, which yields an approximation of Q one step better than the current one. This is the core of the DQN algorithm, as shown in the original paper showing DQL, “Playing Atari with Reinforcement Learning” from 2013 by Mnih et al.:\

The more episodes the agent trains for, the better it gets (and the longer training takes). The agent plays using an epsilon-greedy policy: with probability epsilon it picks a random action, and with probability 1-epsilon it runs the DQN on the current state, and picks the action that got the highest Q-value (i.e. highest expected reward). Typically, we have epsilon start at a high value so that the agent explores new possiblities, and decay it with each step so that the agent exploits its available knowledge more and more.

After carrying out the action, the agent stores the corresponding transition in the replay memory. It then samples a random batch of transitions from the replay memory (sampling a random batch is better than sampling sequential transitions, since sequential transitions are more correleated).

The agent then computes the MSE targets, called y_j in the algorithm, using the Bellman equation. Note that if the state is terminal, there’s no next state, so the target is just the reward for the terminal state. Finally, the algorithm applies a GD step on the MSE between the targets and the outputs of the DQN. \

Putting It All Together

To summarize:

- The agent plays the game for a certain number of episodes

- The agent maintains a replay buffer containing a record of past transitions

- To train the DQN, the agent samples a random batch of transitions from the replay buffer, and performes GD on an MSE loss function

- To get the values predicted by the network, we run the DQN on each state in the sampled batch, and get the Q-value corresponding to the action actually taken in the transition (since the DQN outputs the Q-values for all actions)

- To get the targets, we apply the Bellman equation to the current Q-values, which is an equation that lets us do iterative updates on the Q-function, to get a slightly better approximation of the Q-function than the current approximation To train the DQN, we create a

DeepQNetworkstruct that contains the net itself, the replay buffer, and the environment:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

use rustgan::layers::*;

use rustgan::neural_net;

use rustgan::neural_net::NeuralNet;

pub struct DeepQNetwork {

memory: ReplayMemory,

model: NeuralNet,

env: Blackjack,

}

This structure is initialized as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

const REPLAY_BUF_SIZE: usize = 10000;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

// The number of values in each observation, i.e. number of things the agent sees

const STATE_SIZE: usize = 3;

// The number of actions: there's only Hit and Stand

const NUM_ACTIONS: usize = 2;

impl DeepQNetwork {

pub fn new() -> DeepQNetwork {

let memory = ReplayMemory::new(REPLAY_BUF_SIZE);

let mut model = NeuralNet::new(50, BATCH_SIZE, 0.003, neural_net::Loss::Mse);

model.add_layer(Box::new(Linear::new(STATE_SIZE, 128)));

model.add_layer(Box::new(ReLU::new()));

model.add_layer(Box::new(Linear::new(128, 128)));

model.add_layer(Box::new(ReLU::new()));

model.add_layer(Box::new(Linear::new(128, NUM_ACTIONS)));

let env = Blackjack::new();

DeepQNetwork { memory, model, env }

}

...

}

The main training loop looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

const EPS_START: f32 = 0.9;

const EPS_END: f32 = 0.05;

const EPS_DECAY: f32 = 1000f32;

impl DeepQNetwork {

...

// Train the network to play blackjack!

pub fn fit(&mut self) {

let mut num_steps = 0f32;

for num_ep in 0..NUM_EPISODES {

// Keep playing until the game is over

while !self.env.is_over() {

let state = self.env.state();

// Epsilon-greedy policy: With probability epsilon select a random action a_t

// otherwise select a_t = max_a Q^{*} (\phi(s_t), a; \theta)

let eps_threshold =

EPS_END + (EPS_START - EPS_END) * (-1f32 * num_steps / EPS_DECAY).exp();

let action = self.eps_greedy_policy(state.clone(), eps_threshold);

// Execute action a_t in game and observe reward r_t and next game state s_{t + 1}

self.env.step(&action);

let next_state = self.env.state();

let reward = self.env.reward();

let transition = Transition::new(

state,

action,

if !self.env.is_over() {

Some(next_state)

} else {

None

},

reward,

);

// Store transition in replay buffer

self.memory.store(transition);

// Perform training step

self.training_step();

num_steps += 1f32;

}

self.env.reset();

}

println!("Num steps: {}", num_steps);

}

...

}

In each episode, the agent plays blackjack until completion, selects an action using the epsilon-greedy policy (as mentioned earlier, epsilon is decayed exponentially each time), which is defined in a function called eps_greedy_policy, which takes in the state, and the current value of epsilon:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

impl DeepQNetwork {

fn eps_greedy_policy(&mut self, state: State, eps_threshold: f32) -> Action {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let x = rng.gen_range(0f32..=1f32);

// Select a random action with probability epsilon

if x <= eps_threshold {

if rng.gen_bool(0.5) {

Action::Hit

} else {

Action::Stand

}

} else {

let results = self.model.forward(&Array2::from(state).view(), false);

match results

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, b), (_, d)| b.total_cmp(d))

.unwrap()

.0

{

0 => Action::Hit,

1 => Action::Stand,

_ => {

println!("Shouldn't happen");

Action::Hit

}

}

}

}

...

}

The function samples a random number from 0 to 1 uniformly. If x is smaller than epsilon (this happens with probability epsilon), it selects a random action. Otherwise, it runs the model on the state, which outputs a vector of 2 scores, one for each action, and selects the maximal index. If the index is 0, the Hit action got the highest score, and if the index is 1, the Stand action got the highest score.

After selecting the action, the agent executes it, and records the transition in the replay buffer. It then calls the function training_step, which does most of the heavy lifting:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

// Discount rate

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99;

impl DeepQNetwork {

fn training_step(&mut self) {

// We can't sample a batch if we have less transitions than the batch size

if self.memory.len() < BATCH_SIZE {

return;

}

// Sample a batch

let transition_batch = self.memory.sample(BATCH_SIZE);

// Compute y_j, which is r_j for terminal next_state, and

// r_j + GAMMA * max_{a'} Q(phi_{j + 1}, a' ; Theta) for non-terminal next_state

// These are the MSE targets

let targets: Vec<f64> = (0..BATCH_SIZE)

.map(|i| {

let transition = transition_batch[i];

// Non-terminal next_state

if let Some(next_state) = transition.next_state() {

// \max_{a'} Q(\phi_{j + 1}, a' ; \Theta)

let next_state_mat = Array2::from(next_state);

let max_next_action = self

.model

.forward(&next_state_mat.view(), false)

.into_iter()

.max_by(|a, b| a.total_cmp(b))

.unwrap();

// Add r_j and multiply by gamma

transition.reward() as f64 + GAMMA * max_next_action

} else {

// Terminal next_state

transition.reward() as f64

}

})

.collect();

// The predictions of the net on each transition

let mut states_mat = Array2::zeros((0, STATE_SIZE));

for transition in &transition_batch {

let state_vec = Array1::from(transition.state());

states_mat.push_row(state_vec.view()).unwrap();

}

// This is a BATCH_SIZExNUM_ACTIONS matrix containing the Q-value for each state-action pair

// The output of the network

let q_values_mat = self.model.forward(&states_mat.view(), true);

let y_hat: Vec<f64> = (0..BATCH_SIZE).map(|i| {

let transition = transition_batch[i];

// The corresponding row in the Q-Values matrix

let q_values = q_values_mat.row(i);

*match transition.action() {

Action::Hit => q_values.get(0).unwrap(),

Action::Stand => q_values.get(1).unwrap(),

}

}).collect();

let targets_mat = Array2::from_shape_vec((1, BATCH_SIZE), targets).unwrap();

let batch_actions: Vec<Action> = transition_batch.iter().map(|transition| transition.action()).collect();

let dy = DeepQNetwork::upstream_loss(q_values_mat, targets_mat, batch_actions);

let mut gradients = self.model.backward(dy).0;

gradients.reverse();

// Perform GD step

for i in 0..self.model.layers.len() {

// The current gradient

let grad = &gradients[i];

// Proceed only if there are parameter gradients

// layers such as ReLU don't have any parameters, so we don't need to update anything

if let (Some(dw), Some(db)) = grad {

self.model.layers[i].update_params(&dw, &db, LEARNING_RATE);

}

}

}

}

If the buffer contains less transitions than the batch size, the functions returns without doing anything, since it can’t sample a batch of sufficient size. Otherwise, it samples a batch, and computes the targets using the Bellman equation. It then creates a matrix whose rows are the states in the random batch, and runs the DQN on the matrix (in training mode) to get the Q-values for all actions, and then selects only the Q-values corresponding to the actions actually taken in the transition.

It then performs a GD step (see the previous post about GANs for how I implemented and used GD). The upstream gradient (i.e. the gradient of the loss WRT the output of the network) is computed using the upstream_loss function. Before seeing this function, let’s see how to derive the upstream gradient.

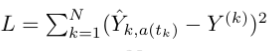

Suppose the output of the network is given to us in an BATCH_SIZExNUM_ACTIONS matrix Y hat, and suppose that the targets are given in an BATCH_SIZE-dimensional vector Y. Recall that the loss is defined as follows:

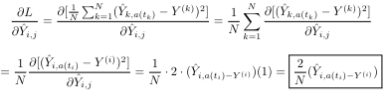

Where N is the batch size, and a(t_k) is the action taken at transition k (so Y hat_{k, a(t_k)} is the Q-value of the action taken at transition k). We want to compute

There are two cases. If j != a(t_i) (i.e. j is not the action taken at transition t_i), then the value of Y hat_{i, j} does not change the loss at all, since it does not even appear in the loss. If so, the gradient WRT Y hat_{i, j} is zero.

If j is equal to a(t_i), then this is just the regular derivation of the gradient of the MSE:

To implement the upstream loss, we simply apply the formula we derived:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

impl DeepQNetwork {

...

// Compute the gradient of the loss WRT the Q-values predicted by the net

// Predictions is an BATCH_SIZExNUM_ACTIONS matrix

// Tragets is an 1xBATCH_SIZE

fn upstream_loss(

predictions: Array2<f64>,

targets: Array2<f64>,

batch_actions: Vec<Action>

) -> Array2<f64> {

let mut gradient = Array2::<f64>::zeros((0, NUM_ACTIONS));

for i in 0..BATCH_SIZE {

let action = &batch_actions[i];

// Compute current row of the gradient matrix

let mut curr_row = vec![0f64, 0f64];

// The nonzero entry in the current row (one of the actions doesn't affect the loss)

let nonzero_idx = match action {

Action::Hit => 0,

Action::Stand => 1,

};

// The Q-value corresponding to the nonzero entry

let nonzero_q_value = predictions.get((i, nonzero_idx)).unwrap();

let target_i = targets.get((0, i)).unwrap();

curr_row[nonzero_idx] = (2.0 / BATCH_SIZE as f64) * (nonzero_q_value - target_i);

gradient.push_row(Array1::from_vec(curr_row).view()).unwrap();

}

gradient

}

...

}

And that’s it! We have a fully-functional DQN that learns how to play blackjack! To make predictions, we use the predict function, which simply runs a forward pass:

1

2

3

4

5

impl DeepQNetwork {

pub fn predict(&mut self, state: State) -> Array2<f64> {

self.model.forward(&Array2::from(state).view(), false)

}

}

Now for the fun part: the experiments!

Experiments

The first thing we’ll do is play a game of blackjack using the agent, and see what it reccomends we do. To do this, we use the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

use std::io::stdin;

use rand::thread_rng;

use rand::distributions::Uniform;

use rand::distributions::Distribution;

use rustdqn::{blackjack::{Blackjack, Action}, dqn::DeepQNetwork};

fn main() {

let mut dqn = DeepQNetwork::new();

dqn.fit();

println!("Alrighty, let's play some blackjack!");

for _ in 0..10 {

let mut game = Blackjack::new();

while !game.is_over() {

let state = game.state();

println!("Game state: {:?}", state);

println!("Agent says: {:?}", dqn.predict(state));

let mut buf = String::new();

println!("Pick an action: ");

println!("1 - Hit\n2 - Stand");

print!("> ");

stdin().read_line(&mut buf).unwrap();

let choice = buf.chars().nth(0).unwrap();

match choice {

'1' => game.step(&rustdqn::blackjack::Action::Hit),

'2' => game.step(&rustdqn::blackjack::Action::Stand),

_ => println!("Unknown action!"),

}

}

println!("Game is over, your reward is: {}", game.reward());

}

}

As written in the code, let’s play some blackjack! We train the agent for 10000 episodes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Alrighty, let's play some blackjack!

Game state: State { hand: 14, face_up: 9, has_ace: false }

Agent says: [[-0.3519276332524875, -0.5128862533341793]], shape=[1, 2], strides=[2, 1], layout=CFcf (0xf), const ndim=2

Pick an action:

1 - Hit

2 - Stand

1

> Game state: State { hand: 19, face_up: 9, has_ace: false }

Agent says: [[-0.645015025857145, 0.5098650621118395]], shape=[1, 2], strides=[2, 1], layout=CFcf (0xf), const ndim=2

Pick an action:

1 - Hit

2 - Stand

2

> Game is over, your reward is: 1

And would you look at that! Remember that the first score in the predictions vector is for Hit, and the second one is for Stand. We start with a hand of 14, and the dealer has a face-up card of 9., and we don’t have an ace. The agent gives a higher score to hitting than standing, so we hit. Then, we draw a 5, so our hand is now 19, and the agent reccomends that we stand. We do that, and win! The second experiment I did was to let the trained agent play 10000 blackjack games, and compare the results (i.e. win/draw/loss amount) with the stats of two other agents:

- An agent that always picks a random action

- An agent that plays the “dealer-strategy” - hits until it gets to a number between 17 and 21 Here’s the code for the random agent:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

use rand::{self, distributions::Uniform, prelude::Distribution, thread_rng};

use rustdqn::blackjack::{self, Blackjack};

// This code tests an agent that acts randomly: it hits/stands with an equal probability

fn main() {

let mut env = Blackjack::new();

let mut victories = 0;

let mut losses = 1;

let mut draws = 0;

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let dist = Uniform::new(0, 2);

for _ in 0..100000 {

while !env.is_over() {

let action = if dist.sample(&mut rng) == 0 {

blackjack::Action::Hit

} else {

blackjack::Action::Stand

};

env.step(&action);

}

if env.reward() > 0f32 {

victories += 1;

} else if env.reward() == 0f32 {

draws += 1;

} else {

losses += 1;

}

env.reset();

}

println!("----RANDOM AGENT STATS----");

println!("Victories: {}", victories);

println!("Draws: {}", draws);

println!("Losses: {}", losses);

}

Here’s the code for the “dealer” agent:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

use rustdqn::blackjack::{self, Blackjack};

// This code tests an agent that acts randomly: it hits/stands with an equal probability

fn main() {

let mut env = Blackjack::new();

let mut victories = 0;

let mut losses = 1;

let mut draws = 0;

for _ in 0..100000 {

while !env.is_over() {

let action = if env.state().hand() < 17 {

blackjack::Action::Hit

} else {

blackjack::Action::Stand

};

env.step(&action);

}

if env.reward() > 0f32 {

victories += 1;

} else if env.reward() == 0f32 {

draws += 1;

} else {

losses += 1;

}

env.reset();

}

println!("----DEALER AGENT STATS----");

println!("Victories: {}", victories);

println!("Draws: {}", draws);

println!("Losses: {}", losses);

}

And here’s the code that tests the trained agent:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

use std::io::stdin;

use rand::thread_rng;

use rand::distributions::Uniform;

use rand::distributions::Distribution;

use rustdqn::{blackjack::{Blackjack, Action}, dqn::DeepQNetwork};

fn main() {

let mut dqn = DeepQNetwork::new();

dqn.fit();

let mut env = Blackjack::new();

let mut victories = 0;

let mut losses = 1;

let mut draws = 0;

for _ in 0..100000 {

while !env.is_over() {

let state = env.state();

let agent_pred = dqn.predict(state);

let action = if agent_pred.get((0, 0)) > agent_pred.get((0, 1)) {

Action::Hit

} else {

Action::Stand

};

env.step(&action);

}

if env.reward() > 0f32 {

victories += 1;

} else if env.reward() == 0f32 {

draws += 1;

} else {

losses += 1;

}

env.reset();

}

println!("----DQN AGENT STATS----");

println!("Victories: {}", victories);

println!("Draws: {}", draws);

println!("Losses: {}", losses);

}

Okay, let’s run them and watch the results:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

----DQN AGENT STATS----

Victories: 44474

Draws: 6730

Losses: 48797

----RANDOM AGENT STATS----

Victories: 30735

Draws: 3986

Losses: 65280

----DEALER AGENT STATS----

Victories: 43723

Draws: 9829

Losses: 46449

Seems like the DQN agent performed best in terms of victories, and the dealer agent performed best in terms of having the least losses. We managed to get a 44.65% increase over the random agent, which is amazing! Training the model for 20000 episodes (instead of 10000) and adding an extra 128-neuron layer (so that the network architecture is now 3x128x128x2) changed the stats to look as follows:

1

2

3

4

----DQN AGENT STATS----

Victories: 44907

Draws: 7577

Losses: 47517

So not much of a change. On more complex problems, I assume that the difference will be more noticable. Another interesting test is whether, given a high hand, the agent has learned that it should stand and not hit. Let’s try giving the agent all possible states where the hand value is > 16, and check on how many states it decides to hit, and on how many states it decides to stand:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

use rustdqn::blackjack::{Blackjack, State};

use rustdqn::dqn::DeepQNetwork;

fn main() {

let mut dqn = DeepQNetwork::new();

let mut stand_ctr = 0;

let mut hit_ctr = 0;

dqn.fit();

println!("Alrighty, let's play some blackjack!");

for hand in 16..=21 {

for face_up in 1..10 {

for has_ace in [true, false] {

let state = State::new(hand, face_up, has_ace);

let dqn_res = dqn.predict(state);

if dqn_res.get((0, 1)) > dqn_res.get((0, 0)) {

stand_ctr += 1;

} else {

hit_ctr += 1;

}

}

}

}

println!("---HIGH HAND RESULTS---");

println!("{} Stands\n{} Hits", stand_ctr, hit_ctr);

}

And here are the results:

1

2

3

---HIGH HAND RESULTS---

107 Stands

1 Hits

Wow! out of 108 total states, it stood for 107 of them. The one state it did hit on, is State { hand: 16, face_up: 9, has_ace: true }. It’s interesting how the agent learned that if it is dealt a high hand, it should only hit if it has an ace, which is a safer play, since an ace can also be counted as a 1.

Summary

In this post, we trained an agent to find a good blackjack strategy using Deep-Q Learning. The training algorithm is very interesting, and I find it amazing that something like this can be accomplished :) Comparing the agent with other strategies (namely an agent that plays randomly, and an agent that plays according to the dealer’s strategy), the agent guided by the DQN perfoms best (in terms of victories)! It has also learned some good strategies: for example, when it is dealt a high hand, in the vast majority of cases, it prefers to stand.

I also think it’s cool that when writing the DQN, I didn’t have to change any code in the library from the previous post :) The complete code for this post is available here. Thanks for reading!

Yoray