Fun With HyperLogLog and SIMD

Introduction

Perhaps the most fundamental property of a set is its cardinality - the number of distinct elements. Computing this measure for an arbitrary list of items seems awfully simple: you read each item (not much wiggle room there), keep track of every distinct item you’ve seen, and at the end return the number of distinct items. You can even use something like a hash table to make lookups of items you’ve already seen faster. Problem solved!

The only problem is that the memory requirements of this algorithm scale linearly with the cardinality, and so eventually we’ll reach a point where we can no longer process our datasets with our available memory amount. To quote the economist Thomas Sowell:

There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.

We’ll either have to invest in more memory, or sacrifice something else. Our existing algorithm doesn’t do much compute, and the vast majority of its resources are spent on reading the input, so there’s not much to do there. Instead of time, then, we’ll agree to introduce a small error to our cardinality estimation, in exchange for using much less memory.

The algorithm we’ll use, which goes by the catchy name HyperLogLog (HLL), uses a very small constant amount of memory, negligible by today’s standards (about 64KB in the highest accuracy setting), and can produce estimations very close to the true cardinality, with an expected error of 0.4%!

In this post, we’ll first derive HLL from first principles, seeing how you could’ve come up with the algorithm yourself, and then implement an initial version in Rust. We’ll then optimize our implementation, using low-level optimizations, from rewriting it using SIMD instructions, to using an efficient memory layout. Finally, we’ll benchmark our implementation against other HLL implementations on multiple datasets, and see where we stand. No prior knowledge of either HLL or SIMD is required.

The code for this post is available here.

HyperLogLog From First Principles

Suppose we have some magic deterministic function f, that, on input x, outputs a uniform random number between 0 and 1. We go through our dataset, running f on every input, and keep track of the minimum output we got. For example, in the below example, the minimum output is 0.1.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

3, f(3) = 0.1

5, f(5) = 0.7

3, f(3) = 0.1

7, f(7) = 0.32

8, f(8) = 0.31

1, f(1) = 0.57

7, f(7) = 0.32

Denote with M the random variable indicating this minimum output. The PDF of M is f(x) = N * (1 - M)^{N - 1}, where N is the number of distinct items in our dataset. This random variable M follows what’s called a Beta distribution, with parameters Beta(1, N), and its mean and variance are 1 / (N + 1) and N / ((N + 1)^2 * (N + 2)), respectively.

In theory, because E[M] = 1 / (N + 1), the quantity 1 / M should give a good estimate for N (in practice the mean and variance of this estimator diverge, though this can be solved, for example by applying log on M beforehand). For example, if we ran f on our dataset, and the minimum number we got was M = 0.0001, we can expect the cardinality of our dataset to be around N = 1000.

Besides the mean and variance diverging, there are two main problems with this estimator. Firstly, it is very susceptible to outliers; just one very small sample, which is not all that uncommon when dealing with large cardinalities, and the estimate is completely ruined. Second, it exhibits the exact problem we were trying to solve; namely, maintaining such a black box requires keeping track of which elements map to which outputs of f, leading again to linear scaling in cardinality.

To solve these problems, instead of relying on such a black box f, we’ll use a strong hash function H, with the assumption that (i) the bits of H are all independent and (ii) the probability of each bit being 0/1 is 0.5. Then, instead of counting the minimum number M, we’ll track the maximum number of leading zeros in each digest. Using similar intuition, if the maximal number of leading zeros we got is 10, we can expect the cardinality of the dataset to be around 1024.

Indeed, mathematically, the PDF of this new discrete random variable M is P(M = k) = (1 - 1 / 2^{k + 1})^N - (1 - 1 / 2^{k})^N (in other words, the probability of all samples having less than k leading zeros, minus the probability of all samples having less than k - 1 leading zeros). As the number of bits in the digest tends to infinity, the expectation approaches E[M] -> log2(N).

This solves the second problem, because computing a hash function doesn’t require us to keep track of any large state, but it doesn’t solve the first problem - this approach is still very susceptible to outliers; just one unlucky digest and our estimate is ruined.

What’s the solution? Use more hash functions! The more hash functions we use, the less susceptible we are to outliers. If we have 4 hash functions for example, we could run each of them for each item in the dataset, track the maximum number of leading zeros we get for each, and then compute something like their harmonic mean, to get a more robust estimate.

In practice, instead of using multiple unrelated hash functions, we’ll just use the same hash function, and bucket their outputs by looking at the first p bits (p is called the precision parameter). More precisely, we’ll keep track of 2^p registers, each holding the maximum number of leading zeros (not including the first p bits) observed in inputs for which the first p bits in the digest are the bucket’s index, and compute the harmonic mean of these registers when we’ve finished going through the entire dataset.

If p = 4, for example, we’ll have 16 registers. Suppose the input x has digest 01000111011111011001001000010110. The first 4 bits are 0b0100 = 4, and the number of leading zeros after that is 1, so we’ll update bucket 4 with the number 1.

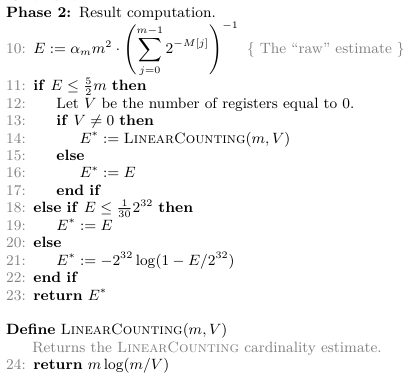

This estimator is still biased, and, for bias correction, we need to multiply it by some other terms, but this is not central to the idea, and we won’t discuss why in this post. There are also some branches for very small cardinalities, such as the LinearCounting branch, but we also won’t discuss these. The final estimate is computed as follows:

Where alpha_m is defined as follows, where m is 2^p:

Workflow

In this section, we’ll implement the algorithm in Rust. In these sorts of performance-critical implementations, it’s useful to have some sort of loss function to guide us through, both in terms of correctness and performance, to make sure we’re improving with each optimization, and not ruining our runtime. To this end, we’ll measure error rate and runtime on the following 3 datasets:

numbers.txt: a file I generated containing 10M random numbers, each with 20 digits.- shakespeare.txt, which, as the name suggests, contains the full works of William Shakespeare.

- creditcard.csv, which is a CSV file containing reports of credit card fraud.

I’ve picked each of these 3 datasets for a different reason which will become clearer later, but all in all they should form a good benchmark. In each dataset, we’ll estimate the amount of distinct lines. Note that in the Shakespeare dataset, for example, this doesn’t have a very interesting meaning, but this is useful to test our implementation regardless.

An Initial Version

When implementing these types of algorithms, it’s best to start from the simplest version and work our way from there, both to understand the algorithm better and avoid premature optimization. In our case, let’s start by reading the file line-by-line, using a BufReader:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

use std::{env, fs::File, io::{self, BufRead, BufReader}, process};

fn main() -> io::Result<()> {

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

if args.len() < 2 {

eprintln!("Usage: {} <filename>", args[0]);

process::exit(1);

}

let file = File::open(&args[1])?;

let reader = BufReader::new(file);

for line in reader.lines() {

...

}

Ok(())

}

Now, let’s think about how we want the HyperLogLog struct to look. The only thing we need to hold are the registers, each of which we’ll assume can be represented in a u8 (this assumption is grounded in reality, as the chance of seeing more than 255 consecutive zeros is negligible). Therefore, we’ll represent it as follows:

1

2

3

4

struct HyperLogLog {

/// A vector of HLL registers

registers: Vec<u8>,

}

Next, let’s implement a new method, which takes in the precision parameter p and constructs a new HyperLogLog:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum HyperLogLogError {

InvalidPrecision(u8),

}

impl HyperLogLog {

pub fn new(p: u8) -> Result<HyperLogLog, HyperLogLogError> {

match p {

4..=16 => {

let registers = vec![0u8; 1 << p];

Ok(HyperLogLog{registers,})

},

_ => Err(HyperLogLogError::InvalidPrecision(p))

}

}

}

If everything is right, we’ll return a new HyperLogLog with 2^p registers. Otherwise, if p isn’t in the range of valid values defined in the Google paper, we’ll return an InvalidPrecision error. The next step involves adding an element to our HLL. Here, we need to make an important design decision: which hash do we use?

After some thinking, I ended up going with MurmurHash3, which is a non-cryptographic hash function commonly used in applications like hash tables. I liked it because it’s easy to implement, and, as we’ll see later, parallelizes pretty well. It has several modes, mostly differing in digest sizes; we’ll go with the 32-bit mode, since it will let us support the largest SIMD batch size, at the cost of preventing us from working with cardinalities close to 2^32.

For now, we’ll use an existing library - we’ll only need to implement the algorithm ourselves when we get to the SIMD part. Back to the insertion function, it will ask for a mutable reference to the HLL, and a reference to a string, and return a result. Its first operation is computing the hash:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

const SEED: u32 = 0u32;

pub fn insert(&mut self, s: &String) -> io::Result<()> {

let hash = murmur3_32(&mut Cursor::new(s), SEED)?;

Ok(())

}

The second parameter passed to murmur3_32 is a seed; throughout the project we’ll use a constant zero seed, though, in real workloads, to get higher precision, we can run multiple runs, each with a different seed, and compare the results. Next, let’s compute the bucket this item goes to by ANDing it with a bit mask all of whose bits are 0, except for the lower p bits which are 1:

1

2

3

// Hack for computing log2 of an integer guaranteed to be a power of 2

let p = self.registers.len().trailing_zeros();

let bucket = hash & ((1 << p) - 1);

To get the leading zeros without including the list p bits, we’ll use the below code, first shifting the hash by p bytes to the right, computing the amount of leading zeros, and then subtracting p - 1, to account for the p top newly-added zero bits:

1

let leading_zeros = ((hash >> p).leading_zeros() - (p - 1 as u32)) as u8;

Finally, we’ll update the corresponding register:

1

2

3

if leading_zeros > self.registers[bucket as usize] {

self.registers[bucket as usize] = leading_zeros;

}

The next function we’ll need to write is the estimation function, which, given the current state of the HLL, estimates how many distinct elements we’ve seen. This function has some annoying branching, but is conceptually pretty simple. Recall that the pseudocode of the estimation function as follows:

Which translates pretty easily to Rust:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

impl HyperLogLog {

...

pub fn estimate(&self) -> f64 {

let m = self.registers.len();

let p = m.trailing_zeros() as usize;

// Raw estimate

let e = PRECOMPUTED_ALPHAS[p - 4]

* (m as f64).powi(2)

* (self.registers.iter().map(|x| 2f64.powf(-(*x as f64))))

.sum::<f64>()

.recip();

match e {

_ if e <= 2.5f64 * (m as f64) => {

// Number of registers equal to 0

let v = self.registers.iter().filter(|x| **x == 0u8).count();

match v {

0 => e,

_ => linear_counting(m, v),

}

}

_ if e <= (1f64 / 30f64) * (2f64.powi(32)) => e,

_ => -2f64.powi(32) * (1f64 - e / 2f64.powi(32)).ln(),

}

}

}

fn linear_counting(m: usize, v: usize) -> f64 {

m as f64 * (m as f64 / v as f64).log2()

}

The PRECOMPUTED_ALPHAS array is defined as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

// Precomputed alphas for bias correction

const PRECOMPUTED_ALPHAS: [f64; 13] = [

0.673,

0.697,

0.709,

0.7152704932638152,

0.7182725932495458,

0.7197831133217303,

0.7205407583220416,

0.7209201792610241,

0.7211100396160289,

0.7212050072994537,

0.7212525005219688,

0.7212762494789677,

0.7212881245439701,

];

And was generated using the below Python script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# Precompute bias-correction alphas

# alpha_16 = 0.673

# alpha_32 = 0.697

# alpha_64 = 0.709

alphas = [0.673, 0.697, 0.709]

# Other alphas are defined by the below formula

for p in range(7, 17):

m = 1 << p

alphas.append(0.7213 / (1 + 1.079 / m))

print(alphas)

We’re finally ready to use the code. Back to the main function, we want to create a new HyperLogLog with some precision parameter p (for starters we’ll use 14), insert each line in the file, and finally call estimate:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

fn main() -> io::Result<()> {

...

let mut hll = HyperLogLog::new(14).unwrap();

for line in reader.lines() {

let line_raw = line?;

hll.insert(&line_raw)?;

}

println!("Estimated cardinality: {}", hll.estimate());

Ok(())

}

Running the Code

Now we’re ready to run the code on our datasets (the true cardinalities are shown above each command):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

(.venv) ➜ release git:(master) ✗ cat numbers.txt | sort | uniq | wc -l

10000000

(.venv) ➜ release git:(master) ✗ ./hll_for_post numbers.txt

Estimated cardinality: 9884845.930477384

(.venv) ➜ release git:(master) ✗ cat shakespeare.txt | sort | uniq | wc -l

111385

(.venv) ➜ release git:(master) ✗ ./hll_for_post shakespeare.txt

Estimated cardinality: 109961.97785177601

(.venv) ➜ release git:(master) ✗ cat creditcard.csv | sort | uniq | wc -l

283727

(.venv) ➜ release git:(master) ✗ ./hll_for_post creditcard.csv

Estimated cardinality: 284331.927915743

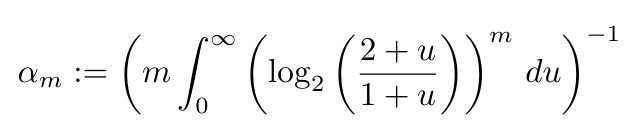

Nice! This amounts to a ~1.15% (relative) error for numbers.txt, a ~1.27% error for shakespeare.txt, and a 0.021% error for creditcard.csv. Just for the sake of it, let’s plot our relative error rates for each dataset with varying values of p:

As we can see, for larger values of p, we start seeing more and more accurate estimations, though at some point we start seeing diminishing returns. The last jump in relative error for shakespeare.txt is because p=16 is large relative to the small cardinality of the Shakespeare dataset, leading to large errors.

Benchmarking

In the last section, we’ve measured the correctness of our implementation, but, because we’ll want to optimize it later, it’s useful to get a baseline of how performant our current code is. To do this, we’ll use the criterion crate.

To use criterion, we’ll need to adjust our code to be a library. This is not all that interesting, so there’s no need to walk through how to do this. The next thing we’ll need to do is modify our Cargo.toml so that it will contain a new benchmark called hll_benchmark:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

[package]

name = "hll_simd"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

murmur3 = "0.5.2"

[dev-dependencies]

criterion = { version = "0.5", features = ["html_reports"] }

[[bench]]

name = "hll_benchmark"

harness = false

Next, in the benches directory, we’ll create a new hll_benchmark.rs file, which will contain our benchmark code. In this file, we’ll create a function which just acts as a wrapper around our implementation, similar to the previous main:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

use std::{

env,

fs::File,

io::{self, BufRead, BufReader},

process,

};

use hll_simd::hll;

fn estimate_file(path: &str) -> f64 {

let file = File::open(path).unwrap();

let reader = BufReader::new(file);

let mut hll = hll::HyperLogLog::new(14).unwrap();

for line in reader.lines() {

let line_raw = line.unwrap();

hll.insert(&line_raw).unwrap();

}

hll.estimate()

}

To define benchmarks on our 3 datasets, we’ll use the bench_function method of criterion:

1

2

3

4

5

fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

c.bench_function("numbers.txt", |b| b.iter(|| estimate_file("data/numbers.txt")));

c.bench_function("shakespeare.txt", |b| b.iter(|| estimate_file("data/shakespeare.txt")));

c.bench_function("creditcard.csv", |b| b.iter(|| estimate_file("data/creditcard.csv")));

}

Finally, we’ll use the criterion_group and criterion_main macros to run our benchmark:

1

2

3

4

5

6

criterion_group!{

name = benches;

config = Criterion::default().sample_size(100);

targets = criterion_benchmark

}

criterion_main!(benches);

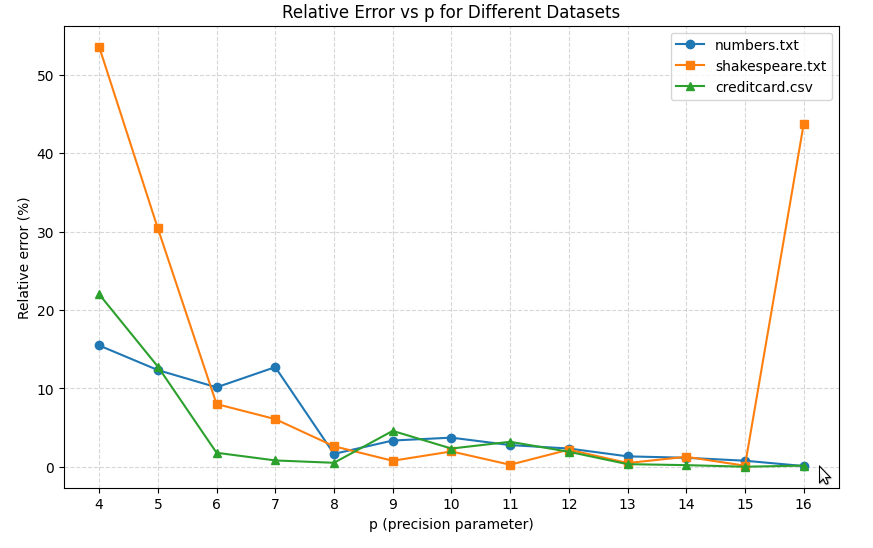

To run the benchmarks, we’ll use cargo bench, which produces a report for each benchmark. The numbers.txt report, for example, looks as follows:

As we can see, our estimated mean runtime is around 640ms, though standard deviation is quite large - about 9% of the mean. The estimated runtime for each dataset is summarized below:

| Estimated Runtime (ms) | Std. Deviation (ms) | |

|---|---|---|

| numbers.txt | 639.92 | 62.478 |

| shakespeare.txt | 14.791 | 0.0009 |

| creditcard.csv | 201.22 | 8.7939 |

Not too shabby, but we can still do better. In the next section, we’ll see how low we can go, and optimize our implementation with SIMD.

Optimization

SIMD 101

The standard (also called scalar) instructions we all know and love, such as add or xor, all operate on a single data stream - for example, running xor r8, r9 XORs r8 with r9 and stores the result in r8. In Flynn’s taxonomy of concurrent processing, we’d say that these instructions are Single Instruction, Single Data (SISD) instructions - you have one instruction that operates on one stream of data.

From here, it’s easy to see how we can think of the idea of Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions: instructions that take in multiple data streams, and operate on all of them concurrently. SIMD instructions have to be, of course, supported on the hardware, so you can’t use them on any CPU, but most modern CPUs support them.

Each SIMD-supporting processor has a different set of SIMD instructions - the i5-13420H powering my laptop, for example, supports an extension called Advanced Vector Extension 2 (AVX2), which introduces 16 new registers YMM0-YMM15, each containing 256 bits, along with new SIMD instructions that can work on these registers - instead of xor, for example, we use the pxor instruction which can work with the SIMD registers.

Case Study: Vector XOR - Scalar

Consider, for example, the following C program, which XORs two vectors:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#define N (1 << 15)

int main() {

uint32_t xs[N];

uint32_t ys[N];

uint32_t zs[N];

// Fill up the buffers

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

xs[i] = i;

ys[i] = 2 * i;

}

// XOR xs and ys

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

zs[i] = xs[i] ^ ys[i];

}

// Sum zs so the compiler will consider it used

uint32_t z_sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

z_sum += zs[i];

}

printf("z_sum = %u\n", z_sum);

return 0;

}

If we compile with -O0, the compiler will use standard scalar instructions for everything - from initializing xs and ys, to XORing them and storing the results in zs, to, finally, summing zs; below are the important instructions corresponding to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

; initializing the two vectors

0x000000000000119d <+52>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020],0x0 ; i <- 0

0x00000000000011a7 <+62>: jmp 0x11de <main+117>

0x00000000000011a9 <+64>: mov edx,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020]

0x00000000000011af <+70>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020]

0x00000000000011b5 <+76>: cdqe

0x00000000000011b7 <+78>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp+rax*4-0x60010],edx ; store i in xs[i]

0x00000000000011be <+85>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020]

0x00000000000011c4 <+91>: add eax,eax

0x00000000000011c6 <+93>: mov edx,eax ; store 2*i in edx

0x00000000000011c8 <+95>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020]

0x00000000000011ce <+101>: cdqe

0x00000000000011d0 <+103>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp+rax*4-0x40010],edx ; store 2*i in ys[i]

0x00000000000011d7 <+110>: add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020],0x1

0x00000000000011de <+117>: cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60020],0x7fff ; is i < N?

0x00000000000011e8 <+127>: jle 0x11a9 <main+64>

...

; XORing x and y and putting the result in z

0x00000000000011ea <+129>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x6001c],0x0

0x00000000000011f4 <+139>: jmp 0x122c <main+195>

0x00000000000011f6 <+141>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x6001c]

0x00000000000011fc <+147>: cdqe

0x00000000000011fe <+149>: mov edx,DWORD PTR [rbp+rax*4-0x60010] ; load xs[i] into edx

0x0000000000001205 <+156>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x6001c]

0x000000000000120b <+162>: cdqe

0x000000000000120d <+164>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp+rax*4-0x40010] ; load ys[i] into eax

0x0000000000001214 <+171>: xor edx,eax ; XOR xs[i] with ys[i] and put the result in edx

0x0000000000001216 <+173>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x6001c]

0x000000000000121c <+179>: cdqe

0x000000000000121e <+181>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp+rax*4-0x20010],edx ; store xs[i] ^ ys[i] in zs[i]

0x0000000000001225 <+188>: add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x6001c],0x1

0x000000000000122c <+195>: cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-0x6001c],0x7fff

0x0000000000001236 <+205>: jle 0x11f6 <main+141>

; Summing zs[i]

0x0000000000001238 <+207>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60018],0x0 ; set zs_sum = 0

0x0000000000001242 <+217>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60014],0x0 ; set i = 0

0x000000000000124c <+227>: jmp 0x126a <main+257>

0x000000000000124e <+229>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60014]

0x0000000000001254 <+235>: cdqe

0x0000000000001256 <+237>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp+rax*4-0x20010] ; load zs[i] into eax

0x000000000000125d <+244>: add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60018],eax ; set zs_sum += zs[i]

0x0000000000001263 <+250>: add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60014],0x1

0x000000000000126a <+257>: cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-0x60014],0x7fff

0x0000000000001274 <+267>: jle 0x124e <main+229>

When measuring 1000 iterations of the above program, with 100 warmup iterations, the average runtime comes out to around 92us with a standard deviation of about 6us.

SIMD Vector XOR

So far, so good. When we compile the code with maximal optimization (-O3), however, the runtime skyrockets into 14us with a standard deviation of 3us - around 6.5x faster! As you might’ve guessed, the reason this happens is due to SIMD. If we inspect the disassembly now, we’ll see that it’s almost unrecognizable compared to the previous code! The code that fills the two vectors now looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

0x00000000000010a1 <+33>: movdqa xmm1,XMMWORD PTR [rip+0xf67] # 0x2010

0x00000000000010a9 <+41>: movdqa xmm2,XMMWORD PTR [rip+0xf6f] # 0x2020

...

0x00000000000010c2 <+66>: xor eax,eax

0x00000000000010c4 <+68>: mov rsi,rsp

0x00000000000010c7 <+71>: lea rcx,[rsp+0x20000]

0x00000000000010cf <+79>: nop

0x00000000000010d0 <+80>: movdqa xmm0,xmm1

0x00000000000010d4 <+84>: paddd xmm1,xmm2

0x00000000000010d8 <+88>: movaps XMMWORD PTR [rsi+rax*1],xmm0

0x00000000000010dc <+92>: pslld xmm0,0x1

0x00000000000010e1 <+97>: movaps XMMWORD PTR [rcx+rax*1],xmm0

0x00000000000010e5 <+101>: add rax,0x10

0x00000000000010e9 <+105>: cmp rax,0x20000

0x00000000000010ef <+111>: jne 0x10d0 <main+80>

What’s going on here? xmm0 is the lower 128 bits of the ymm0 SIMD register mentioned above (in theory ymm0 would’ve yielded better performance, but the compiler chose not to use it, and, indeed, manually telling it to use YMM registers does not improve performance - trust the compiler!).

The first two movdqa instructions load some values from memory into the two XMM registers xmm1 and xmm2. If we inspect this value, we can see that xmm1 contains the 4 32-bit integers 0, 1, 2, 3, and xmm2 contains the integers 4, 4, 4, 4.

Inside the loop which initializes xs and ys, the next interesting instruction is movdqa xmm0, xmm1, which, like it sounds, copies the values in xmm1 to xmm0. Right after that, we add the values in xmm2 to those in xmm1, so that in the first iteration, xmm0 will contains 0, 1, 2, 3, in the second 4, 5, 6, 7, and so on.

Now it’s clear - these are exactly the values which we want to write to xs! The only difference is that now we write 4 of these values at a time, in the movaps XMMWORD PTR [rsi+rax*1],xmm0 instruction.

Next, we execute a pslld xmm0, 0x1 - a logical shift left by 1, or, in other words, a multiplication by 2. The next instruction is a movaps XMMWORD PTR [rcx+rax*1],xmm0, which writes these values to ys. After this, we add 16 to rax, and compare it to 0x20000 - the number of iterations. Note that this time, we have 4x less iterations, due to the usage of SIMD!

The next interesting part is here:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0x00005555555550f1 <+113>: xor eax,eax

0x00005555555550f3 <+115>: lea rdx,[rsp+0x40000]

0x00005555555550fb <+123>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

0x0000555555555100 <+128>: movdqa xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rsi+rax*1]

0x0000555555555105 <+133>: pxor xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rcx+rax*1]

0x000055555555510a <+138>: movaps XMMWORD PTR [rdx+rax*1],xmm0

0x000055555555510e <+142>: add rax,0x10

0x0000555555555112 <+146>: cmp rax,0x20000

0x0000555555555118 <+152>: jne 0x555555555100 <main+128>

We move 128 bits a time from xs into xmm0 (in the movdqa xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rsi+rax*1]), use pxor to XOR them with the corresponding 128 bits in ys, and then move the result to zs. Again, we have 4x less iterations!

Finally, to sum zs, we use the following code - we essentially store 4 integer sums in xmm0 (the top 32 bits store the sum of all elements of zs with i % 4 = 0, the next 32 bits store the sum of all elements of zs with i % 4 = 1 and so on), and then do some bit manipulations to get a 32 bit sum:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

0x000055555555511d <+157>: pxor xmm0,xmm0 ; zero z_sum

0x0000555555555121 <+161>: lea rdx,[rsp+0x60000] ; load the end address of zs into rdx

0x0000555555555129 <+169>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

0x0000555555555130 <+176>: paddd xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rax] ; add 4 elements of zs to the sums in xmm0

0x0000555555555134 <+180>: add rax,0x20

0x0000555555555138 <+184>: paddd xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rax-0x10] ; add 4 elements of zs to the sums in xmm0

0x000055555555513d <+189>: cmp rdx,rax ; have we finished reading zs?

0x0000555555555140 <+192>: jne 0x555555555130 <main+176>

0x0000555555555142 <+194>: movdqa xmm1,xmm0

0x0000555555555146 <+198>: xor eax,eax

0x0000555555555148 <+200>: mov edi,0x2 ; not important, related to printf

0x000055555555514d <+205>: psrldq xmm1,0x8

0x0000555555555152 <+210>: lea rsi,[rip+0xeab] # 0x555555556004 ; not important, related to printf

0x0000555555555159 <+217>: paddd xmm0,xmm1

0x000055555555515d <+221>: movdqa xmm1,xmm0

0x0000555555555161 <+225>: psrldq xmm1,0x4

0x0000555555555166 <+230>: paddd xmm0,xmm1

0x000055555555516a <+234>: movd edx,xmm0

0x000055555555516e <+238>: call 0x555555555070 <__printf_chk@plt>

Hopefully, the concept of SIMD is clearer now, and we can start using it to optimize our HLL implementation!

Using SIMD For HLL

To understand how we can use SIMD, let’s go through the general flow of our implementation once again:

- We open a file and read it, line by line.

- We insert each line separately to the HLL, entailing the following operations:

- Hashing the line.

- Performing some bit manipulation to extract the bucket index and the number of leading zeros.

- Conditionally (i.e. if the number of leading zeros is greater than the one stored in the corresponding register) writing the number of leading zeros to the register.

- Estimating the cardinality using the values stored in the registers.

We don’t have much to optimize in step 1 and step 3 (step 3 in particular only takes a negligible portion of our runtime), so we’ll optimize 2. To do this, we have 2 main optimization paths:

- Optimize the computation of a hash on a single string.

- Use SIMD to hash (and insert) multiple strings at once.

To decide which option is more viable. we’ll first need to understand how the hash we’re using, MurmurHash3, works, which we’ll do in the next section.

MurmurHash3 Internals

Throughout this section, we’ll focus only on the 32-bit mode, which is the one we’ll end up using. A nice way to understand how it works is to implement it, which is exactly what we’ll do. First, some constants:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

const C1: u32 = 0xcc9e2d51;

const C2: u32 = 0x1b873593;

const R1: u32 = 15;

const R2: u32 = 13;

const M: u32 = 5;

const N: u32 = 0xe6546b64;

const BLOCK_SIZE: usize = 4;

Our function will take in a string and a 32-bit seed, and return the 32-bit digest. The first thing we do is initialize the 32-bit state as the seed:

1

2

3

pub fn murmur3_32(s: &String, seed: u32) -> u32 {

let state = seed;

}

Next, we’ll read the string in 4-byte blocks. If the last block is smaller than 4 bytes, we don’t read it, and process it at a later stage. The exact operation done on each 4-byte block is just a couple of bit manipulations and such; there’s nothing very interesting about it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

let mut blocks = s.as_bytes().chunks_exact(BLOCK_SIZE);

// Read string in 4-byte blocks

for block in &mut blocks {

let mut k = u32::from_le_bytes(block.try_into().unwrap());

k = k.wrapping_mul(C1);

k = k.rotate_left(R1);

k = k.wrapping_mul(C2);

state ^= k;

state = state.rotate_left(R2);

state = (state.wrapping_mul(M)).wrapping_add(N);

}

Next, if there are any, we read the remainder bytes, and apply a similar operation on them, also XORing them into the state:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Handle the tail

let tail = blocks.remainder();

let mut remaining_bytes = match tail.len() {

1 => tail[0] as u32,

2 => ((tail[1] as u32) << 8) | tail[0] as u32,

3 => ((tail[2] as u32) << 16) | ((tail[1] as u32) << 8) | tail[0] as u32,

_ => 0u32,

};

remaining_bytes = remaining_bytes.wrapping_mul(C1);

remaining_bytes = remaining_bytes.rotate_left(R1);

remaining_bytes = remaining_bytes.wrapping_mul(C2);

state ^= remaining_bytes;

Finally, we apply a finalization step on the state, and return it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Finalization

state ^= s.len() as u32;

state ^= state >> 16;

state = state.wrapping_mul(0x85ebca6b);

state ^= state >> 13;

state = state.wrapping_mul(0xc2b2ae35);

state ^= state >> 16;

state

Back to the Drawing Board

As we can see, the state of MurmurHash3 is only 4 bytes long, so SIMD won’t help a lot on a single string compared to other hashes with longer states, where there’s more work to be done. If so, we are left with the second option: parallelizing across batches. To do this, we’ll need to implement two functions:

- Computing MurmurHash3 across a batch of N strings, and returning N digests.

- Given N digests, updating our register state with all of them at once.

We’ll start with the first bullet. In the next section, we’ll see how to use SIMD in Rust, and then how to implement the hash.

Paralellizing MurmurHash3

Rust has multiple ways to use SIMD, which vary in their closeness to the hardware, and, correspondingly, their hardware independence. In this post, we’ll use std::simd, which sits an the hardware-independent end of the spectrum. Unfortunately, as of the time of writing of this post, this component is only available in Rust nightly. To configure our project to use nightly, we’ll add the following file, rust-toolchain.toml:

1

2

[toolchain]

channel = "nightly"

And to use SIMD, we’ll add the following feature at the top of lib.rs:

1

#![feature(portable_simd)]

To parallelize the algorithm, instead of holding one state, we’ll just hold multiple states - one for each string in the batch. The signature of our function is as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

use std::simd::{LaneCount, Simd, SupportedLaneCount};

pub(crate) fn murmur3_32<const N_ELEMS: usize>(

batch: &[String; N_ELEMS],

seeds: Simd<u32, N_ELEMS>,

) -> Simd<u32, N_ELEMS>

where

LaneCount<N_ELEMS>: SupportedLaneCount,

{

todo!()

}

We take in a batch of N_ELEMS strings, and a Simd vector of N_ELEMS u32’s, and return a Simd vector of N_ELEMS u32’s - the digest of each string. To make the batch size flexible (so that, for example, it will work on hardware that supports AVX512 - a more recent SIMD extension to Intel processors), we template the function in N_ELEMS, and introduce the SupportedLaneCount constraint on N_ELEMS. This constraint is only satisfied for lane counts the SIMD backend knows how to handle.

As in the scalar implementation, our first operation is initializing the state with the seed. The only difference is that now our state is larger:

1

let mut states = seeds;

Next, we want to handle the body of each string concurrently. Here, we encounter our first problem - each string can have a different length! Our first solution to this problem will just be to iterate according to the number of blocks the longest string contains, zero-pad strings that aren’t as long, and introduce a “work mask” of sorts, so that we only change the state for blocks that aren’t padding.

We’ll start with computing the number of complete 4-byte blocks in each string:

1

2

3

4

// Max number of blocks in our batch, not incl. the tail

let num_blocks = batch.map(|s| s.len() / BLOCK_SIZE);

let num_blocks_simd = Simd::from_array(num_blocks);

let max_num_blocks = *num_blocks.iter().max().unwrap();

We’ll now iterate until we’ve read the last complete block in the longest string in the batch. The first thing we do is read the corresponding block in each string (or zero if it doesn’t exist) into a SIMD vector:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

...

for i in 0..max_num_blocks {

// Load the current block of each string if it exists, and 0 o/w

let ks_vec: Vec<u32> = (0..N_ELEMS)

.map(|j| {

if i < num_blocks[j] {

u32::from_le_bytes(

batch[j].as_bytes()[BLOCK_SIZE * i..BLOCK_SIZE * (i + 1)]

.try_into()

.unwrap(),

)

} else {

0

}

})

.collect();

...

let mut ks = Simd::from_slice(&ks_vec);

}

...

We then compute a work mask, which is a vector whose i-th element if true if the current block we’re reading from the i-th string is “real”, and false if it is padding:

1

2

// Which states do we actually update?

let work_mask = Simd::splat(i).simd_lt(num_blocks_simd);

In the Rust API, Simd::splat creates a SIMD vector whose elements are all the argument - so Simd::splat(i) creates a new SIMD vector of N elements all of whose elements are i. We then perform the same work we did in the scalar version on ks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

fn simd_rol<const N: usize>(a: Simd<u32, N>, ramt: u32) -> Simd<u32, N>

where

LaneCount<N>: SupportedLaneCount,

{

(a << Simd::splat(ramt)) | (a >> Simd::splat(32 - ramt))

}

ks *= Simd::splat(C1);

ks = simd_rol(ks, R1);

ks *= Simd::splat(C2);

Finally, we conditionally update the states according to the work mask:

1

2

3

4

5

states = work_mask.cast().select(states ^ ks, states);

states = work_mask.cast().select(simd_rol(states, R2), states);

states = work_mask

.cast()

.select(states * Simd::splat(M) + Simd::splat(N), states)

The select method selects, for each true element in the mask, the corresponding value in the first argument, and for each false element the corresponding value in the second argument. In our case, we use the false elements as a no-op, to keep the states as they are.

The next part handles the tails - we first read them into a SIMD vector, then perform the multiplication and rotation operations on them, and finally XOR them into the states. Note that now we don’t need to use a mask, since elements that have no tail will have a tail of 0, which won’t affect the XOR:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

// Process tails

let mut tails = Simd::from_array(batch.map(|s| {

let offset = (s.len() / BLOCK_SIZE) * BLOCK_SIZE;

let s_bytes = s.as_bytes();

match s.len() % BLOCK_SIZE {

1 => s_bytes[offset] as u32,

2 => ((s_bytes[offset + 1] as u32) << 8) | (s_bytes[offset] as u32),

3 => {

((s_bytes[offset + 2] as u32) << 16)

| ((s_bytes[offset + 1] as u32) << 8)

| (s_bytes[offset] as u32)

}

_ => 0u32,

}

}));

tails *= Simd::splat(C1);

tails = simd_rol(tails, R1);

tails *= Simd::splat(C2);

states ^= tails;

Finally, we finalize the states as in the scalar version, and return them:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Finalize state

states ^= Simd::from_array(batch.map(|s| s.len() as u32));

states ^= states >> Simd::splat(16);

states *= Simd::splat(0x85ebca6b);

states ^= states >> Simd::splat(13);

states *= Simd::splat(0xc2b2ae35);

states ^= states >> Simd::splat(16);

states

Parallelizing Insertion

Now that we have a function for hashing a batch of data concurrently, let’s write out the insertion component. We’ll create a new function insert_batch, that takes in a mutable reference to the HLL and a batch of strings, and updates the HLL with all of them. The function starts by hashing every string using the function we’ve just written:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

use crate::murmur3_simd::murmur3_32 as murmur3_32_simd;

impl HyperLogLog {

...

pub fn insert_batch<const N: usize>(&mut self, s: [&String; N])

where

LaneCount<N>: SupportedLaneCount,

{

let hashes = murmur3_32_simd(&s, Simd::splat(SEED));

}

...

}

Next, we’ll compute the bucket each string goes to using logic similar to the scalar case:

1

2

let p = self.registers.len().trailing_zeros();

let buckets = hashes & Simd::splat((1 << p) - 1);

Likewise, we’ll compute the number of leading zeros of each hash in the batch:

1

let leading_zeros = (hashes >> Simd::splat(p)).leading_zeros() - (Simd::splat(p - 1));

The write logic, however, is a bit different. Instead of a conditional write, we’ll split the update into 3 steps:

- Reading each register in the indices specified in

buckets(this is called a gather in SIMD terminology). - Computing an elementwise maximum between these values and the leading zeros vector.

- Writing the vector we get in step 2 to each of the indices specified in

buckets(called a scatter in SIMD terminology).

In Rust, this looks as below:

1

2

3

4

let to_write =

Simd::gather_or_default(&self.registers, buckets.cast()).simd_max(leading_zeros.cast());

to_write.scatter(&mut self.registers, buckets.cast());

We’re finished with the first SIMD version. To see how well we fare against the scalar version, we’ll add in the below benchmark function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

fn estimate_file_batched(path: &str) -> f64 {

const N: usize = 8;

let file = File::open(path).unwrap();

let reader = BufReader::new(file);

let mut hll = hll::HyperLogLog::new(14).unwrap();

let mut insert_batch = Vec::with_capacity(N);

for line in reader.lines() {

let line_raw = line.unwrap();

insert_batch.push(line_raw);

if insert_batch.len() == N {

hll.insert_batch::<N>(

insert_batch

.iter()

.map(|s| s)

.collect::<Vec<&String>>()

.try_into()

.unwrap(),

);

insert_batch = Vec::with_capacity(N);

}

}

hll.estimate()

}

It’s mostly identical to the last benchmark, except we read lines in batches of 8, and then add them in a batched manner. Running the benchmarks, we get the following results (shown in a table with the old ones):

| Estimated Runtime (ms) - scalar | Std. Deviation (ms) - scalar | Estimated Runtime (ms) - SIMD | Std. Deviation (ms) - SIMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers.txt | 639.92 | 62.478 | 759.99 | 21.190 |

| shakespeare.txt | 14.791 | 0.0009 | 18.419 | 0.385 |

| creditcard.csv | 201.22 | 8.7939 | 185.05 | 3.192 |

Huh?! Wasn’t SIMD supposed to improve our performance? Why are we worse on most benchmarks?

Optimizing SIMD

On the vector XOR C program we wrote earlier, SIMD resulted in a speedup of about 6.5x, so what changed here? The largest difference is that our C program was almost purely made of compute, while in the Rust program, we need to read data from disk, then load it into vectors, and only then being able to work with the SIMD registers - this obviously involves more I/O.

Another factor that’s killing our performance is memory layout. Recall that in the C program, our loads all looked like movdqa xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rsi+rax*1] - in other words, they read from sequential memory using only one instruction. Our Rust code, in contrast, both during the hashing code and the update code, reads and writes data to completely separate locations in memory, which incur more I/O overhead.

To solve the first problem, we’ll try to overlay I/O operations on top of compute using two threads, so that while we operate on one batch of data, the other thread is already fetching the second batch. We’ll solve the second problem by laying out memory in a smarter way, so that loads, at least, will all access contiguous memory.

Memory Layout

Suppose we have a batch of 8 strings, each containing 5 4-byte blocks. We’ll denote blocks belonging to the first string with [0], blocks belonging to the second string with [1], and so on. Our memory is currently laid out similar to the following pattern (note that this is not precisely correct, since we also store the metadata of String, but this is the core idea):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

[0][0][0][0][0]

[1][1][1][1][1]

[2][2][2][2][2]

[3][3][3][3][3]

[4][4][4][4][4]

[5][5][5][5][5]

[6][6][6][6][6]

[7][7][7][7][7]

The reads we dispatch, however, are column-major - we read the first block of the first string, then the first block of the second string, and so on. Each one of these reads generates a new load. To make reads faster, we’ll introduce a new preprocessing step, that transposes the above memory, making it look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

[0][1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

[0][1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

[0][1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

[0][1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

[0][1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Note that we’ll also need to handle padding correctly, adding zero bytes where necessary. This also incurs some extra overhead for actually, well, laying out the memory, but doing so typically results in noticeably better performance despite the overhead. Let’s get to business!

We’ll first create a new function, preprocess_batch, also templated in N_ELEMS, which takes in N_ELEMS Strings, and returns a vector of u32s - the transposed batch as shown above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#[inline(always)]

fn preprocess_batch<const N_ELEMS: usize>(

batch: &[&String; N_ELEMS],

) -> Vec<u32>

where

LaneCount<N_ELEMS>: SupportedLaneCount,

{

todo!()

}

In this function, we’ll first convert each of the input strings into their bytes, using as_bytes. Then, we’ll calculate the maximum number of blocks (not including the tail) inside the batch, iterate over all strings this many times, and push the corresponding word if one exists, and zero padding otherwise to the output vector:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

let batch_bytes = batch.map(|s| s.as_bytes());

// Number of blocks in each string in the batch not incl. tail

let num_blocks = batch_bytes.map(|s| s.len() / BLOCK_SIZE);

let num_blocks_max = num_blocks.iter().max().unwrap();

let mut out = Vec::with_capacity((num_blocks_max + 1) * N_ELEMS);

for i in 0..*num_blocks_max {

for (j, s) in batch_bytes.iter().enumerate() {

// If block i exists in string j

if i < num_blocks[j] {

out.push(u32::from_le_bytes(s[BLOCK_SIZE*i..BLOCK_SIZE*(i+1)].try_into().unwrap()));

} else {

// Otherwise, pad

out.push(0);

}

}

}

...

Tail handling is pretty similar to what we’ve done so far:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Handle tails

for s in batch_bytes {

let offset = (s.len() / BLOCK_SIZE) * BLOCK_SIZE;

out.push(match s.len() % BLOCK_SIZE {

1 => s[offset] as u32,

2 => ((s[offset + 1] as u32) << 8) | (s[offset] as u32),

3 => ((s[offset + 2] as u32) << 16) | ((s[offset + 1] as u32) << 8) | ((s[offset] as u32)),

_ => 0u32,

});

}

out

Now, we’ll just need to change our existing code to use this new memory layout. We’ll add in a new call to preprocess_batch at the start of the hashing function, and then change our complex existing reads:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

let ks_vec: Vec<u32> = (0..N_ELEMS)

.map(|j| {

if i < num_blocks[j] {

u32::from_le_bytes(

batch[j].as_bytes()[BLOCK_SIZE * i..BLOCK_SIZE * (i + 1)]

.try_into()

.unwrap(),

)

} else {

0

}

})

.collect();

let mut ks = Simd::from_slice(&ks_vec);

...

let mut tails = Simd::from_array(batch.map(|s| {

let offset = (s.len() / BLOCK_SIZE) * BLOCK_SIZE;

let s_bytes = s.as_bytes();

match s.len() % BLOCK_SIZE {

1 => s_bytes[offset] as u32,

2 => ((s_bytes[offset + 1] as u32) << 8) | (s_bytes[offset] as u32),

3 => {

((s_bytes[offset + 2] as u32) << 16)

| ((s_bytes[offset + 1] as u32) << 8)

| (s_bytes[offset] as u32)

}

_ => 0u32,

}

}));

…To simple contiguous reads from the preprocessed batch:

1

2

3

4

5

let preprocessed_batch = preprocess_batch(batch);

...

let mut ks = Simd::from_slice(&preprocessed_batch[i..i+N_ELEMS]);

...

let mut tails = Simd::from_slice(&preprocessed_batch[preprocessed_batch.len()-N_ELEMS..preprocessed_batch.len()]);

Benchmarking

Running our benchmarks on the new version yields the following results:

| Estimated Runtime (ms) - scalar | Std. Deviation (ms) - scalar | Estimated Runtime (ms) - SIMD | Std. Deviation (ms) - SIMD | Estimated Runtime (ms) - SIMD v2 | Std. Deviation (ms) - SIMD v2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers.txt | 639.92 | 62.478 | 759.99 | 21.190 | 720.79 | 1.18 |

| shakespeare.txt | 14.791 | 0.9 | 18.419 | 0.385 | 15.15 | 0.172 |

| creditcard.csv | 201.22 | 8.7939 | 185.05 | 3.192 | 123.92 | 0.844 |

Interesting! First of all, we can observe a significant performance improvement on all datasets. On the numbers.txt and shakespeare.txt datasets, we’re still worse than scalar, though by less than earlier, and on creditcard.csv, we’re now about 1.6x better than scalar!

Here would be a good moment to stop and try to figure out why our improvement factors on each of the datasets is so different. Performance-wise, HLL obviously doesn’t care whether the data in each file is a line from Hamlet or a 1999 credit fraud event in west Kazakhstan. If so, the main statistics which differentiate each dataset are (a) the number of lines and (b) the length of each line. We can observe these statistics in the following table:

| # Lines | Mean line length (blocks) | Line Length Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| numbers.txt | 10M | 5 | 0 |

| shakespeare.txt | 124,456 | 11.05 | 4.461 |

| creditcard.csv | 284,808 | 132.5 | 1.454 |

Let’s unpack what this means:

- For

numbers.txt, each string in a batch of N strings contains exactly 5 blocks. The reason SIMD might not really help here, and even be worse than scalar, is twofold. First, 5 blocks is small by scalar standards, so by the time you’ve laid out the data nicely for SIMD in a vector, and iterated worked over it in SIMD, scalar might’ve already finished with the batch faster. Second, random writes (scatters), namely to theregistersfield ofHyperLogLog, is an expensive operation which, as you’ll recall, scalar performs conditionally (i.e. only if the max changes). SIMD, on the other hand, scatters every time, regardless of whether there is actually a change. - On

shakespeare.txt, not only are the strings still relatively short, but the std. deviation is very high - almost half of the mean. Therefore, preprocessing the data for SIMD incurs a large overhead, and much of the compute is wasted on padding, for example, which scalar has no need for. - On

creditcard.csv, however, our line length is large enough for SIMD to start making a change, and the standard deviation is very low relative to the mean, so not much compute is wasted, and we are more efficient than scalar.

In the next section, we’ll implement one last optimization, allowing for running compute in parallel with I/O.

Multithreading

Our next optimization is more high-level than what we’ve done so far, and tackles our implementation running like so:

- Read first N lines

- Process them

- Read next N lines

- Process them

- …

In other words, while processing batch i, we make no effort to try to load batch i+1 in advance. This is especially critical on files with long lines, such as creditcard.csv which SIMD is already most effective on, and therefore we should try to squeeze every bit of performance on.

Instead of our current approach, what we can do is start two threads: a producer and a consumer. The producer’s job is to read batches of N lines from the file (the I/O work). The consumer will hold a HyperLogLog, read the batches read by the producer via a channel, and insert them into the HLL. Finally, the consumer will call estimate, and return the estimated cardinality.

In this approach, while the consumer is performing the compute-heavy part of our workload, the producer handles the I/O part, and we won’t be I/O-blocked anymore. To implement this, we’ll first create an mpsc synchronous channel that can hold two batches at a time:

1

2

3

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 8;

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::sync_channel::<Vec<String>>(2);

Next, we’ll create the consumer thread:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

let handle = thread::spawn(move || {

let mut hll = hll::HyperLogLog::new(14).unwrap();

while let Ok(batch) = rx.recv() {

if batch.len() < BATCH_SIZE { break; }

hll.insert_batch::<8>(batch.iter()

.map(|s| s)

.collect::<Vec<&String>>()

.try_into()

.unwrap(),);

}

hll.estimate()

});

Finally, in our main thread, we’ll iterate over the file’s lines, and send batches to the consumer. We’ll then signal to the consumer that it can stop by sending an empty batch, and return the estimated cardinality:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

let mut batch = Vec::with_capacity(BATCH_SIZE);

for line in reader.lines() {

batch.push(line.unwrap());

if batch.len() == BATCH_SIZE {

tx.send(batch).unwrap();

batch = Vec::with_capacity(BATCH_SIZE);

}

}

if !batch.is_empty() {

tx.send(batch).unwrap();

}

tx.send(Vec::new()).unwrap();

handle.join().unwrap()

Benchmarking

Using this approach, our new results are:

| Estimated Runtime (ms) - SIMD v2 | Std. Deviation (ms) - SIMD v2 | Estimated Runtime (ms) - Multithreading | Std. Deviation (ms) - Multithreading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers.txt | 720.79 | 1.18 | 3376 | 205.74 |

| shakespeare.txt | 15.15 | 0.172 | 36.5 | 3.2906 |

| creditcard.csv | 123.92 | 0.844 | 155.37 | 9.939 |

How can this be?! Multithreading decimated our performance.

Multithreading v2

Contrary to our expectations, not only did multithreading not improve our performance, it made it worse, even going so far as a factor of 4x slowdown on some datasets. With multithreading, in theory, we should read batches of 8 lines, while concurrently processing already-read batches and inserting them into our HLL.

8 lines, however, is a very small number; it probably takes our producer thread much less time to read 8 lines (especially on datasets with short lines, such as numbers.txt), than it takes the consumer to insert them into the HLL. This leads to an imbalance between the two threads: the producer thread gets blocked very often, waiting for the consumer thread to process the batches it has already sent.

In other words, we’re back to the original problem, but with the added overhead of managing multiple threads and a channel that communicates between them. Not very good. The solution, however, is quite simple - use a larger batch! We’ll now have two units of work:

- 8 lines, which is how many lines are actually inserted at a time to the HLL.

- A larger batch of, say, 4096 lines, which is the size read by the producer and sent to the consumer.

The consumer will now just iterate over the 4096-line batch in sub-batches of 8 lines, hopefully solving our problem. The code for the consumer thread now looks as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

while let Ok(batch) = rx.recv() {

if batch.is_empty() { break; }

for i in (0..batch.len()).step_by(8) {

hll.insert_batch::<8>(batch[i..i+8].iter()

.map(|s| s)

.collect::<Vec<&String>>()

.try_into()

.unwrap(),);

}

}

Benchmarking

| Estimated Runtime (ms) - SIMD v2 | Std. Deviation (ms) - SIMD v2 | Estimated Runtime (ms) - Multithreading | Std. Deviation (ms) - Multithreading | Estimated Runtime (ms) - Multithreading v2 | Std. Deviation (ms) - Multithreading v2 | Scalar Mean | Scalar Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers.txt | 720.79 | 1.18 | 3376 | 205.74 | 1002 | 47.56 | 639.92 | 62.478 |

| shakespeare.txt | 15.15 | 0.172 | 36.5 | 3.2906 | 16.23 | 0.4767 | 14.791 | 0.0009 |

| creditcard.csv | 123.92 | 0.844 | 155.37 | 9.939 | 98.41 | 3.376 | 201.22 | 8.7939 |

As we can see, using a larger batch has improved our performance by a massive factor on creditcard.csv, and we are now about 2x faster than scalar! On the other datasets, we are still slower than scalar, but these are, in any case, not the types of datasets we try to optimize for. I assume it is possible to get even better performance by tuning the batch size, or even updating the batch size dynamically during a run, but we won’t handle these types of optimizations in this post.

Comparing Against External Libraries

And that’s it for the implementation side of things! To see how well we did, in this section, we’ll benchmark other HLL libraries written in multiple languages on our 3 datasets, and see how well we fare against them. To keep things fair, I’ve only used libraries where the hash function can be configured to use MurmurHash3, since if we’d just insert a MurmurHash3 digest, only for it to be hashed further down the line with another hash function, it wouldn’t be an apples-to-apples comparison.

In each of the following sections, we’ll create a small benchmark setup around each library, and finally summarize our findings. With each of the libraries, to be consistent with our Rust benchmark setup, we’ll run 100 samples, and report the mean runtime. Each library will be run with p=14.

Datasketch (Python)

Datasketch is a probabilistic data structure library written in pure Python, with about (at the time of writing), 2.8k stars on GitHub. For running MurmurHash3, we’ll use the mmh3 package. By default, this package returns a signed integer, so we’ll need to AND it with 0xffffffff in our wrapper:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

from datasketch import HyperLogLog

import mmh3

from statistics import mean, stdev

def estimate_file(path):

hll = HyperLogLog(p=14, hashfunc=lambda x: mmh3.hash(x) & 0xffffffff)

# Process file line by line

with open(path, "r") as f:

for line in f.readlines():

hll.update(line.encode("utf-8"))

return hll.count()

Next, we’ll run the wrapper on our 3 files using timeit:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

if __name__ == "__main__":

import timeit

numbers_txt = timeit.repeat("estimate_file('../../data/numbers.txt')", number=1, repeat=100, globals=locals())

shakespeare_txt = timeit.repeat("estimate_file('../../data/shakespeare.txt')", number=1, repeat=100, globals=locals())

creditcard_csv = timeit.repeat("estimate_file('../../data/creditcard.csv')", number=1, repeat=100, globals=locals())

print(f"For numbers.txt: mean={mean(numbers_txt)} stdev={stdev(numbers_txt)}")

print(f"For shakespeare.txt: mean={mean(shakespeare_txt)} stdev={stdev(shakespeare_txt)}")

print(f"For creditcard.csv: mean={mean(creditcard_csv)} stdev={stdev(creditcard_csv)}")

Axiom (Go)

To benchmark with a lower-level library, we’ll go with Axiom’s hyperloglog library, which, as far as I can see, is the most popular HLL library for Go, coming in at about 1K GitHub stars. First, we’ll implement a function runOnce, which takes in a filename, and runs their HLL on each line. The MurmurHash3 implementation we use is spaolacci/murmur3. We use the InsertHash method to prevent the library from applying an additional hash:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

func runOnce(filename string) error {

hll := hyperloglog.New14()

file, err := os.Open(filename)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer file.Close()

hasher := murmur3.New32()

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(file)

for scanner.Scan() {

line := scanner.Text()

hasher.Reset()

hasher.Write([]byte(line))

hashValue := hasher.Sum32()

hll.InsertHash(uint64(hashValue))

}

_ = hll.Estimate()

return scanner.Err()

}

Next, we’ll add a BenchmarkFiles method, which iterates over a list of files, runs the wrapper on each of them 100 times, and reports the mean and standard deviation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

var files = []string{

"../../../data/numbers.txt",

"../../../data/shakespeare.txt",

"../../../data/creditcard.csv",

}

func BenchmarkFiles(b *testing.B) {

const samples = 100

for _, fname := range files {

b.Run(fname, func(b *testing.B) {

times := make([]float64, 0, samples)

for i := 0; i < samples; i++ {

b.StartTimer()

start := b.Elapsed()

if err := runOnce(fname); err != nil {

b.Fatalf("error on %s: %v", fname, err)

}

elapsed := b.Elapsed() - start

b.StopTimer()

// convert to milliseconds

ms := float64(elapsed.Nanoseconds()) / 1e6

times = append(times, ms)

}

// compute mean + stdev

var sum float64

for _, t := range times {

sum += t

}

mean := sum / float64(samples)

var variance float64

for _, t := range times {

diff := t - mean

variance += diff * diff

}

stdev := math.Sqrt(variance / float64(samples))

fmt.Printf("%s: mean=%.6f ms, stdev=%.6f ms (over %d runs)\n",

fname, mean, stdev, samples)

})

}

}

This can be run with go test -bench ..

Datadog (Go)

Another Go library! This time, runOnce looks as follows (BenchmarkFiles is pretty much identical):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

func runOnce(filename string) error {

hll, err := hyperloglog.New(1 << 14)

file, err := os.Open(filename)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer file.Close()

hasher := murmur3.New32()

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(file)

for scanner.Scan() {

line := scanner.Text()

hasher.Reset()

hasher.Write([]byte(line))

hashValue := hasher.Sum32()

hll.Add(hashValue)

}

_ = hll.Count()

return scanner.Err()

}

Hyperloglogplus (Rust)

Finally, we’ll compare against another Rust implementation: hyperloglogplus, which appears to be the most popular implementation in Rust, with about 1.5M downloads on crates.io. We’ll also benchmark this library with criterion. First, we’ll need to implement the BuildHasher trait for Murmur3 to allow hyperloglogplus to use it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

use std::hash::{BuildHasher, Hasher};

use murmur3::murmur3_32;

use std::io::Cursor;

pub struct Murmur3Hasher {

state: u32,

}

impl Murmur3Hasher {

pub fn new() -> Self {

Self { state: 0 }

}

}

impl Hasher for Murmur3Hasher {

fn finish(&self) -> u64 {

// Just return lower 64 bits (you can choose upper if you want)

self.state as u64

}

fn write(&mut self, bytes: &[u8]) {

let mut cursor = Cursor::new(bytes);

self.state = murmur3_32(&mut cursor, 0).unwrap();

}

}

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct Murmur3BuildHasher;

impl BuildHasher for Murmur3BuildHasher {

type Hasher = Murmur3Hasher;

fn build_hasher(&self) -> Self::Hasher {

Murmur3Hasher::new()

}

}

And we’ll implement a criterion benchmark similar to ours (hppplus is the name of my custom crate I’m using to benchmark, to not add a dependency for hyperloglogplus in our SIMD implementation):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

use criterion::{Criterion, criterion_group, criterion_main};

use hppplus::Murmur3BuildHasher;

use std::{

fs::File,

io::{self, BufRead, BufReader},

};

use hyperloglogplus::{HyperLogLog, HyperLogLogPF};

fn estimate_file_external(path: &str) -> f64 {

let file = File::open(path).unwrap();

let reader = BufReader::new(file);

let mut hll: HyperLogLogPF<String, _> = HyperLogLogPF::new(14, Murmur3BuildHasher).unwrap();

for line in reader.lines() {

let line_raw = line.unwrap();

hll.insert(&line_raw);

}

hll.count()

}

fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

c.bench_function("numbers.txt", |b| {

b.iter(|| estimate_file_external("../../../data/numbers.txt"))

});

c.bench_function("shakespeare.txt", |b| {

b.iter(|| estimate_file_external("../../../data/shakespeare.txt"))

});

c.bench_function("creditcard.csv", |b| {

b.iter(|| estimate_file_external("../../../data/creditcard.csv"))

});

}

criterion_group! {

name = benches;

config = Criterion::default().sample_size(100);

targets = criterion_benchmark

}

criterion_main!(benches);

Results

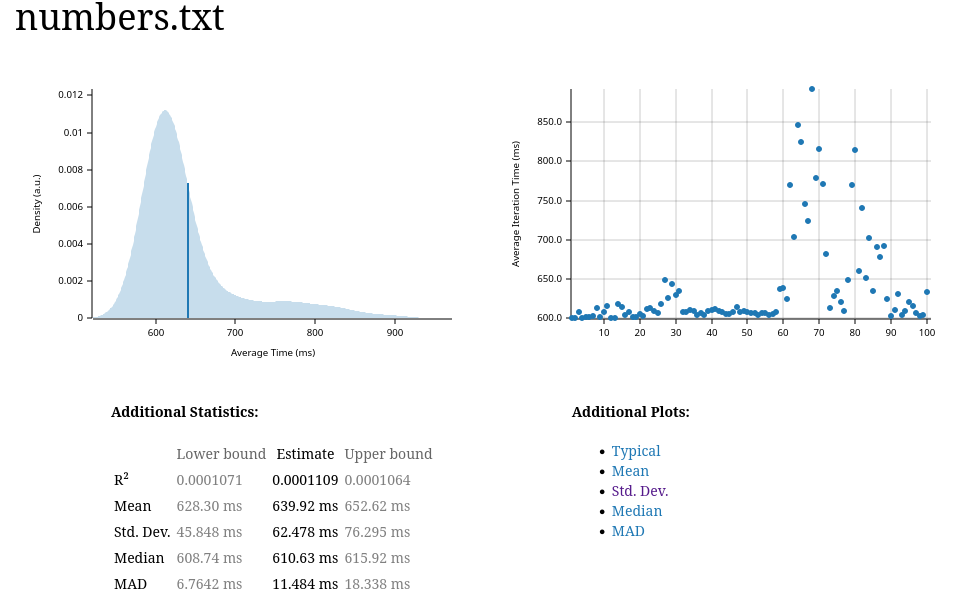

Below, we show the benchmark results:

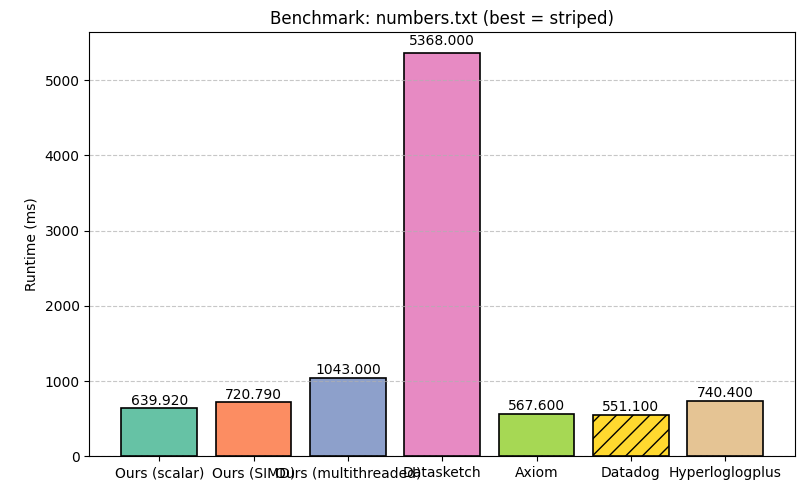

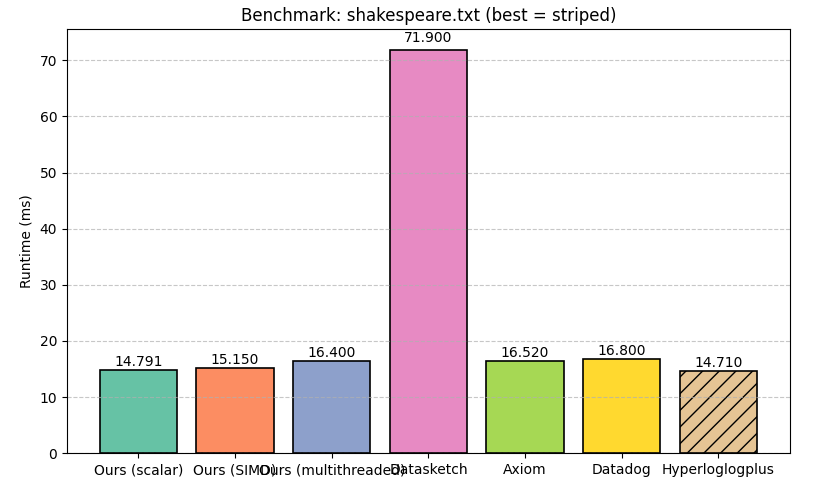

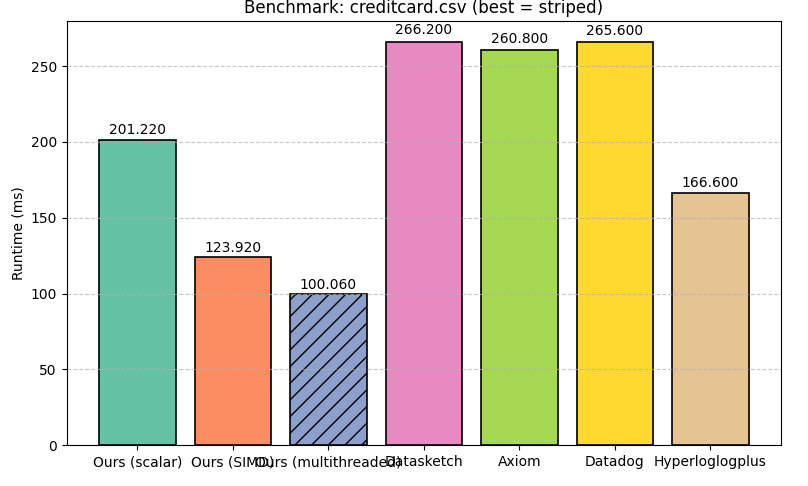

In each benchmark, the most performant implementation is highlighted. As we can see, on numbers.txt, the Go implementations perform the best, followed by our scalar Rust implementation, then our SIMD implementation, and then hyperloglogplus. On shakespeare.txt, all implementations perform similarly, with hyperloglogplus winning, and on creditcard.csv, our multithreaded implementation performs the best.

Conclusion

Let’s recap what we did:

- Understood how HyperLogLog works and how we could’ve come up with it.

- Implemented a basic version in Rust.

- Used the

criterioncrate to benchmark our implementation. - Learned how SIMD works, down to the assembly level, and how to use it in Rust.

- Optimized our implementation using SIMD.

- Added multithreading to improve performance.

- Benchmarked our implementation against other HyperLogLog libraries written in multiple languages.

I’ve known about HyperLogLog for quite a long time now, first seeing them in this YouTube video), but always felt like I needed to work on a project involving it to understand it better. A couple of weeks ago, this Computerphile video popped up in my Recommended videos, and I knew this was a sign :)

This was also my first time developing with SIMD, and it is definitely not an easy cheat that can accelerate programs in seconds - as you’ve seen, most of the optimizations are very algorithm specific, and you need to think about them to implement them correctly. Long optimization, while exhausting at some points, is very satisfying, and seeing all the millisecond-level improvements cumulate in our implementation being faster than multiple existing libraries was very fun.

Another important lesson we can learn is that some optimizations are data-specific - as we’ve seen, our implementations work especially well on data with long lines, while in some cases being even worse than scalar on data with very short lines, or when standard deviation is very high.

That’s also part of the fun, and at some point I’d like to adapt this implementation to handle these cases more smartly, using solutions such as fallback to scalar, or a smart online statistical analysis of the data to determine optimal batch sizes. Another optimization we could’ve done is to represent each register using less than a byte, which would use even less memory. As these suggest, this is definitely not the end of this rabbit hole, and there is a lot more work to be done.

Additionally, at some point I’d like to implement an optimized implementation on a GPU, using CUDA or Metal. The architecture there is entirely different, which leads to other interesting design choices and optimizations. That, though, will also be left for another post :).

Thank you for reading! The code is available here.

Yoray

Enjoyed this post? Consider buying me a coffee!