Solving The Millionaires' Problem in Rust

Introduction

Can two millionaires, Alice and Bob, compare their wealth privately (i.e. without learning anything about each other’s wealth)? This is one of the most fundamental problems in the field of Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC), and though it might seem impossible at first glance, many solutions have been proposed to this problem since it was posed in 1982 by Andrew Yao in his seminal paper Protocols for Secure Computation. In this post, we implement a protocol to solve this problem from scratch in Rust, using some fascinating cryptographic tools: Oblivious Transfer and Garbled Circuit. Prior knowledge of basic cryptography (e.g. the differences between symmetric/asymmetric cryptography) is assumed, but all of the SMPC algorithms are explained in the post. We also assume knowledge of basic boolean algebra.

Note: throughout the code, we’ll use some APIs (RSA and AES-CTR) I wrote in previous posts ([1], [2]). Using the APIs is pretty simple, but if you want to understand how they work, check out those posts! The code for this post is available here.

Formalizing The Problem

The problem presented in the previous section (2-party private comparison) is a special case of the following, general problem:

Given N parties, where each party i has a value x_i, and a function f that takes in N inputs, Evaluate f(x_1, …, x_N) without any party learning anything about the values of the other parties

In our case, N=2, and the function implements a boolean comparison: f(x_1, x_2) = x_1 < x_2 ? 1 : 0. When discussing an SMPC problem, as usual in crypto, we need to define the threat model. In SMPC, there are two main models, differentiated by the honesty of the parties:

- In the Semi-Honest Model, the participants in the protocol have to follow the protocol, and do not deviate from it in an attempt to “cheat” and change the protocol’s outcome. This model is called “semi-honest” rather than “completely-honest” since the parties can still passively analyze the messages exchanged.

- In the Active Model, the participants are allowed to arbitrarily deviate from the protocol and send incorrect data. For example, Alice may try to lie to Bob and convince him that she is richer than him (despite this being false).

Protocols secure under the active model are more complicated, and hence are out-of-scope for this post. The protocol we’ll construct in this post is only secure under the semi-honest model; we assume the participants follow the protocol without trying to manipulate the outcome. In the next section, we’ll discuss the first part of the protocol, which consists of converting the function we want to evaluate (in our case comparison) into a form that is easier to work with.

Boolean Circuits

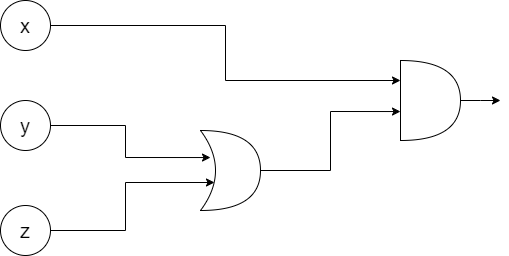

You’re probably already familiar with boolean functions – functions that take in N boolean inputs and return M boolean outputs. For example, F(x, y, z) = x(y + z) is a boolean function that takes in 3 boolean values and returns a single value. Such functions can be represented graphically using a DAG, where the nodes represent gates and inputs, and the edges (called wires) represent inputs to gates. For example, the previous function can be represented as follows:

The outgoing edge from the last AND gate contains the output of the circuit. This graphical model is called a boolean circuit. Since most things that can be done on a computer can be done using boolean algebra, we can represent an incredibly wide family of functions using circuits, including our comparison function.

Implementing Circuits in Rust

Circuits are DAGs, and the circuit only has a single output (x > y), so the most natural representation would ae a binary tree. In addition to the tree’s root, we store the number of inputs the circuit takes in. Doing so allows us to index the circuit’s inputs correctly later on when we’ll evaluate the circuit.

1

2

3

4

5

6

/// The circuit is represented as a binary tree

pub struct Circuit {

out: Node,

/// Number of inputs to the circuit

n: usize,

}

When evaluating a circuit, we have to pass in a boolean value for each input node. Therefore, we’ll define Node as an enum with two variants:

Input, in which case we store the index of their input value (when evaluating the circuits, we’ll pass in the inputs as aVec<bool>)- Or

Gate, in which case we store the left child, right child, and the gate’s operation

In Rust, we represent this as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

/// A node in the circuit

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub enum Node {

/// An input node through which the inputs to the circuit are passed; the usize indicates the input id

Input(usize),

/// A logic gate represented with a 4-bit integer

Gate(u8, Box<Node>, Box<Node>),

}

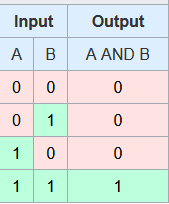

You might wonder how the operation of the gate is represented using a u8. To answer this, we have to think of the gate as a truth table. AND, for example, is represented as follows:

We can think of evaluating the gate’s output on two inputs A and B as performing a lookup in the truth table’s output column. If we store the output column as a 4-bit integer (e.g. AND is represented as 0b1000), we could perform the lookup using bitwise operations. For example, on input A=0 and B=1, we can calculate A && B = 0b1000 & (1 << 0b01) = 0, and similarily on inputs A=1 and B=1, we’ll calculate A && B = 0b1000 & (1 << 0b11) = 1. As is common when working with binary trees, we’ll use recursion to evaluate the circuit on a given input. We define a function eval on Circuit that wraps an eval function defined on the circuit’s output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

impl Node {

pub fn eval(&self, input: &Vec<bool>) -> bool {

match self {

Node::Input(idx) => input[*idx],

Node::Gate(op, left, right) => {

// Index into the gate's operation based on the inputs

let (left_val, right_val) = (left.eval(input), right.eval(input));

(op & (1 << (2

* left_val as usize + right_val as usize))) != 0

}

}

}

...

}

impl Circuit {

...

pub fn eval(&self, input: &Vec<bool>) -> bool {

self.out.eval(input)

}

}

If the current Node is an Input, the eval function simply looks up its value in the vector of inputs that was passed to eval. Otherwise, the function evaluates the values of its left and right children, and looks up the corresponding value in the gate’s operation (2 * left_val as usize + right_val as usize converts the values to the index).

Cool! Let’s test our code on a small circuit:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

const AND_GATE: u16 = 0b1000u16;

const OR_GATE: u16 = 0b1110u16;

const XOR_GATE: u16 = 0b0110u16;

#[test]

pub fn complex_circuit_test() {

// x & ((x | y) ^ z)

let x = Node::Input(0);

let y = Node::Input(1);

let z = Node::Input(2);

let or = Node::Gate(OR_GATE, Box::new(x.clone()), Box::new(y));

let xor = Node::Gate(XOR_GATE, Box::new(or), Box::new(z));

let out = Node::Gate(AND_GATE, Box::new(x), Box::new(xor));

let circuit = Circuit::new(out);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![false, false, false]), false);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![false, false, true]), false);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![false, true, false]), false);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![false, true, true]), false);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![true, false, false]), true);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![true, false, true]), false);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![true, true, false]), true);

assert_eq!(circuit.eval(&vec![true, true, true]), false);

}

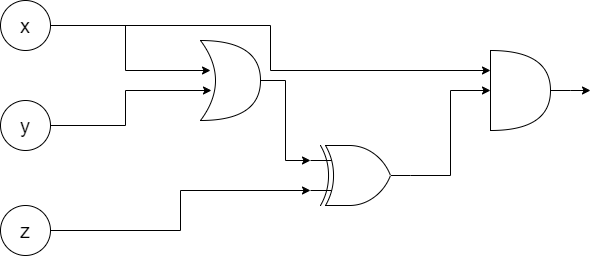

Or, represented graphically:

The test passes, so let’s move on to the next section, where we’ll implement the cryptographical algorithms.

Oblivious Transfer

The Protocol

The algorithm we’ll implement in the next section relies on a cryptographic primitive called Oblivious Transfer (OT). Classic 1-2 OT concerns two parties: the Sender and the Receiver. The sender holds two messages (hence the “1-2” in the name) m_0 and m_1. The receiver wants to get one of the sender’s messages (i.e. m_i where 0 <= i <= 1), but without the sender knowing which message they sent (i.e. without learning i). This is crucial for privacy-critical applications, like SMPC problems.

To solve this problem, we’ll use an RSA-based protocol proposed by Even, Goldreich, and Lempel. The protocol works as follows:

- The sender starts by generating an RSA keypair and sending the public key

(e, N)to the receiver (in practice the public key should be authenticated somehow, but in our toy implementation we won’t handle this). - In addition, the sender generates two messages x_0 and x_1, and sends them to the receiver.

- The receiver chooses the desired message index b, and a random number k.

- The receiver then computes

v = (x_b + k ** e) % N, and sends the result to the sender. Note that because the sender doesn’t know k, it cannot extract the value of x_b In other words, computing $v$ blinds the value of x_b. - Using v, the sender now computes

k_0 = (v - x_0) ** d % Nandk_1 = (v - x_1) ** d % N. Note that for index b, we havek_b = (v - x_b) ** d % N = (x_b + k ** e - x_b) ** d % N = (k ** e) ** d % N = k. - Using k_0 and k_1, the sender then computes

m'_0 = (m_0 + k) % Nandm'_1 = (m_1 + k) % N, and sends both of these to the receiver. - Because

k_b = k, the receiver can now computem_b = (m'_b - k) mod Nand getm_b.

Note that nowhere in this protocol does the sender learn anything about the index the client chose!

The Implementation

As mentioned in the intro, we’ll use the RSA code I wrote in a previous post about making a secure chat in Rust to implement this. We’ll begin by defining a struct ObTransferSender that holds the sender’s information:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

/// Oblivious transfer

/// Alice (the Sender) has two messages m_0 and m_

1. Bob (the Receiver) wants to receive

/// message m_b, without Alice finding out which message he received

pub struct ObTransferSender {

msgs: (BigUint, BigUint),

/// RSA keypair

keypair: Keypair,

/// Random messages

xs: (BigUint, BigUint),

}

When initializing a new ObTransferSender from two messages and a keypair, we generate x_0 and x_1:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

impl ObTransferSender {

/// Generate a new sender

pub fn new(msgs: (BigUint, BigUint), keypair: Keypair) -> ObTransferSender {

// The x's are two random messages smaller than the RSA modulus

let xs = (

thread_rng().gen_biguint_below(&keypair.public.n),

thread_rng().gen_biguint_below(&keypair.public.n),

);

ObTransferSender {

msgs,

keypair,

xs,

}

}

...

}

Similarily, we’ll define a struct called ObTransferReceiver that handles the receiver’s side of things. As input to its new function, it takes in the sender’s public key, x_0, and x_1, and generates k randomly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

/// OT from the receiver's POV

pub struct ObTransferReceiver {

/// The xs sent by the sender

xs: (BigUint, BigUint),

/// Used to blind the message index

k: BigUint,

/// Sender's pubkey

sender_pubkey: PublicKey,

}

impl ObTransferReceiver {

pub fn new(sender_pubkey: PublicKey, xs: (BigUint, BigUint)) -> ObTransferReceiver {

let k = thread_rng().gen_biguint_below(&sender_pubkey.n);

ObTransferReceiver {

xs,

k,

sender_pubkey,

}

}

...

}

Next, we’ll define the function that blinds x_b given the index b:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

impl ObTransferReceiver {

...

/// Generate the blinded x_b given the index b

pub fn blind_idx(&self, b: usize) -> BigUint {

((if b == 0 {

&self.xs.0

} else {

&self.xs.1

}) + self.k.modpow(&self.sender_pubkey.e, &self.sender_pubkey.n))

% &self.sender_pubkey.n

}

}

Given the output v from this function, the sender computes the combined messages m’_0 and m’_1:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

impl ObTransferSender {

...

/// Generate the combined messages that allow the receiver to derive the message they want

/// v is the blinded x the receiver wants

pub fn gen_combined(&self, v: BigUint) -> (BigUint, BigUint) {

let n = &self.keypair.public.n;

let (x_0, x_1) = &self.xs;

let (k_0, k_1) = (

self.keypair.private.decrypt(&((&v + (n - x_0)) % n)),

self.keypair.private.decrypt(&((&v + (n - x_1)) % n)),

);

// Combine with the secret messages

let (m_0, m_1) = &self.msgs;

((m_0 + k_0) % n, (m_1 + k_1) % n)

}

}

Finally, the receiver extracts the desired message from those outputted by gen_combined as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

impl ObTransferReceiver {

...

/// Derive the selected message from the sender's reply

pub fn derive_msg(&self, m_primes: (BigUint, BigUint), b: usize) -> BigUint {

((if b == 0 { m_primes.0 } else { m_primes.1 }) + (&self.sender_pubkey.n - &self.k))

% &self.sender_pubkey.n

}

}

Let’s test everything to make sure it works (in the real implementation, of course, we’ll have to transfer the structures over the network and not locally):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

#[test]

fn oblivious_transfer_test() {

let sender_pubkey = Keypair::new(None, None);

let sender = ObTransferSender::new((123u64.into(), 456u64.into()), sender_pubkey.clone());

let xs = sender.xs();

let receiver = ObTransferReceiver::new(sender_pubkey.public, xs);

let v = receiver.blind_idx(0);

let m_primes = sender.gen_combined(v);

let extracted_msg = receiver.derive_msg(m_primes, 0);

assert_eq!(extracted_msg, sender.msgs().0);

}

Awesome! Now with the OT building block ready, we can start implementing the Garbled Circuit protocol.

Garbled Circuits

The Simple Case

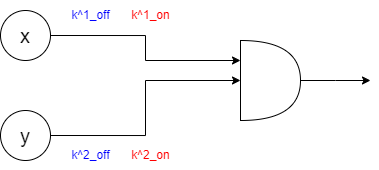

Throughout this section, we’ll assume that instead of privately evaluating an arbitrary circuit, the two parties each have one bit (Alice has bit x and Bob has bit y), and they want to compute x AND y privately. This will make understanding the algorithm simpler, and later on we’ll see how to transfer what we’ve learned to arbitrary circuits. We begin by looking at our circuit graphically:

One agreed-upon party, called the garbler, assigns two keys to each wire (wires are edges connecting two components) in the circuit: the on key and the off key, resulting in the following setup:

Now, for each gate in our circuit (in our simplified case there’s only one gate – the AND gate), the garbler computes 4 ciphertexts; one for each possible pair of inputs:

- c_00 = E(k^1_off, E(k^2_off, 0 AND 0)) = E(k^1_off, E(k^2_off, 0))

- c_01 = E(k^1_off, E(k^2_on, 0 AND 1)) = E(k^1_off, E(k^2_on, 0))

- c_10 = E(k^1_on, E(k^2_off, 1 AND 0)) = E(k^1_on, E(k^2_off, 0))

- c_11 = E(k^1_on, E(k^2_on, 1 AND 1)) = E(k^1_on, E(k^2_off, 1))

Where E is some encryption function (we’ll use AES in CTR mode). What we’re essentially doing is encrypting all possible outputs of the gate based on the input keys. This operation is called garbling, and hence the name “Garbled Circuits”. In the next step, the garbler sends the other party (called the receiver) the 4 ciphertexts. In addition, the garbler sends the key for the wire through which the garbler’s bit is sent based on the garbler’s bit (so if the garbler’s bit x is 0, the garbler sends k^1_off, and if the garbler’s bit is 1, it sends k^1_on). Note that knowing this key doesn’t tell the receiver anything about the garbler’s bit, since the key is just that: a key. In the next step, using the OT primitive we’ve built earlier, the receiver gets the matching key for the wire through which y is sent (wire 2) based on the receiver’s bit. Suppose the garbler’s bit is 1 and the receiver’s bit is 0. Then at this point, the receiver has the following information:

- c_00

- c_01

- c_10

- c_11

- k\^1_on

- k\^0_off

Using these, the receiver can try to decrypt each of the 4 ciphertexts using the keys it has. Since only one of the ciphertexts was encrypted using these exact two keys, only one ciphertext will decrypt to a number, and the others will decrypt to gibberish! In this case, only c_10 will decrypt to 0, and so the receiver learns that the output of the circuit, when evaluated with these two inputs, is 0. Finally, the receiver sends this value to the garbler. Throughout the entire process, the receiver didn’t learn anything about the garbler’s bit (and vice versa), since all of the computations were performed on encrypted values! In the next section, we’ll see how to generalize this principle to privately evaluate arbitrary circuits.

Arbitrary Circuits

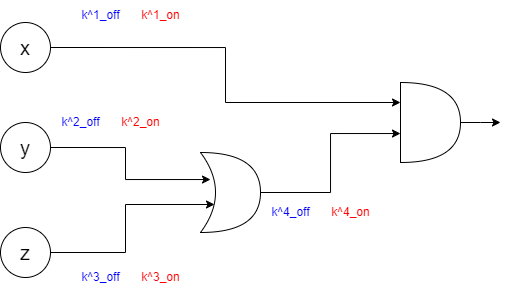

While taking this principle and applying it to arbitrary circuits might seem complicated, there’s actually not a whole lot to it. Consider the following circuit (we’ve already seen it in the “Boolean Circuits” section):

As before, we assign a key to each wire in the circuit:

This time, for each gate (except for the output gate), instead of encrypting either a 0 or a 1, we encrypt the gate’s output wire’s keys. In the output gate, we encrypt a 0 or a 1 as before. For example, for the OR gate in the above circuit, we compute the ciphertexts as follows:

- c_00 = E(k^2_off, E(k^3_off, k^4_off)) (we encrypt k^4_off since 0 OR 0 = 0)

- c_01 = E(k^2_off, E(k^3_on, k^4_on)) (we encrypt k^4_on since 0 OR 1 = 1)

- c_10 = E(k^2_on, E(k^3_off, k^4_on))

- c_11 = E(k^2_on, E(k^3_on, k^4_on))

The receiver can then use the previously discussed principle to evaluate all gates in the circuit, eventually leading to the output gate, which will output either a 0 or a 1.

The astute among you might’ve noticed that with the introduction of keys as gate outputs, the receiver cannot distinguish between the random gibberish resulting from incorrect decryptions, and the correct keys, since after all keys are just random data. To solve this problem, we append a constant amount of zeros to each plaintext prior to encryption so that the receiver will be able to understand which of the keys is correct.

The Implementation

Garbling

As with OT, we’ll need to implement both the garbler’s and the receiver’s side of things. For the garbler, we define a struct GarbledCircuit in a very similar manner to Circuit:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

/// A garbled circuit from the garbler's POV

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct GarbledCircuit {

out: GarbledNode,

input_wires: HashMap<usize, GarbledWire>,

n: usize,

}

For now, ignore the input_wires field. Just like a Node, a GarbledNode is an enum with two variants: Input and GarbledGate:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

/// Possible nodes in a GarbledCircuit (analogous to `Node` in a regular Circuit)

pub enum GarbledNode {

Input(usize),

Gate(Rc<RefCell<GarbledGate>>),

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

/// A garbled gate (from the garbler's POV, i.e. we know the gate's keys and operation unlike the receiver)

pub struct GarbledGate {

c_00: Option<Vec<u8>>,

c_01: Option<Vec<u8>>,

c_10: Option<Vec<u8>>,

c_11: Option<Vec<u8>>,

pub left: Option<Rc<RefCell<GarbledNode>>>,

pub right: Option<Rc<RefCell<GarbledNode>>>,

left_wire: Option<GarbledWire>,

right_wire: Option<GarbledWire>,

parent_wire: Option<GarbledWire>,

op: Option<u8>,

}

impl GarbledGate {

/// Generate a new gate from the gate's parent, and the new gate's operation

fn new(parent_wire: Option<GarbledWire>, op: u8) -> Self {

GarbledGate {

c_00: None,

c_01: None,

c_10: None,

c_11: None,

left: None,

right: None,

left_wire: None,

right_wire: None,

parent_wire,

op: Some(op),

}

}

...

}

The role of the Input variant is identical to the Input variant in Node. In GarbledGate, we store the ciphertexts, the left and right children, the operation, and 3 wires – the wires connecting the gate to its children, and the one connecting the gate to its parent (the output wire). Each GarbledWire stores its on key and its off key:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

const KEY_SIZE: usize = 32;

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct GarbledWire {

on_key: [u8; KEY_SIZE],

off_key: [u8; KEY_SIZE],

}

Now, let’s write the garbling algorithm (i.e. converting from a Circuit to a GarbledCircuit):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

impl From<Circuit> for GarbledCircuit {

/// Garble a circuit

fn from(value: Circuit) -> Self {

// Generate the input wire keys

let n = value.n();

let mut input_wires = HashMap::new();

for i in 0..n {

input_wires.insert(i, GarbledWire::new());

}

// Garble the output node (this garbled the entire circuit)

let garbled_out =

GarbledNode::garble(value.out(), Some(GarbledWire::out_wire()), &input_wires);

let garbled_out = garbled_out.as_ref().unwrap().borrow();

GarbledCircuit::new(garbled_out.clone(), input_wires, n)

}

}

In the input_wires HashMap, we map input indices to the wires connecting them to other gates in the circuit. This is done to prevent a situation where an input is connected to multiple gates with multiple wires, but each wire has different keys. After constructing the HashMap, we call the actual garbling function, garble on the circuit’s output node. As the other parameters, we pass GarbledWire::out_wire() (a wire whose on key and off key are only 1s and only 0s, respectively), and the input_wires HashMap. After this, we construct a new GarbledCircuit with the garbled output. The garble function begins by matching on its input node. If the input node is of type Node::Input, we simply construct a GarbledNode::Input with the same index:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

impl GarbledNode {

/// Recursively garble a circuit

fn garble(

node: Node,

parent_wire: Option<GarbledWire>,

input_wires: &HashMap<usize, GarbledWire>,

) -> Option<Rc<RefCell<GarbledNode>>> {

match node {

// If this node is an input node, just transform it to a `GarbledInput::Input`

// with the same input index

Node::Input(idx) => Some(Rc::new(RefCell::new(GarbledNode::Input(idx)))),

Node::Gate(op, left, right) => {

...

}

}

}

}

If the input node is a gate, we start by constructing a new GarbledGate whose parent wire is the parent wire passed to garble:

1

2

3

4

5

6

Node::Gate(op, left, right) => {

// Construct the gate we'll output

let out_node = Rc::new(RefCell::new(GarbledGate::new(parent_wire, op)));

...

}

Then, we generate the wires connecting the current node to its left and right children. If a child is an input, this amounts to performing a lookup in the input_wires HashMap. Otherwise, we generate new wires with random keys:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

// If our left child is an Input node, get the wire connecting us to the left child

// by looking up the input node's index in the input wires

// Otherwise, create a new wire

let left_wire = if let Node::Input(idx) = *left {

input_wires.get(&idx).unwrap().clone()

} else {

GarbledWire::new()

};

// Same goes for the right child

let right_wire = if let Node::Input(idx) = *right {

input_wires.get(&idx).unwrap().clone()

} else {

GarbledWire::new()

};

We then recursively call garble on our left and right children, passing as parameters the newly computed wires (since the parent wires of a node’s children are those connecting the children to the node):

1

2

3

4

// Call recursively on our children; the left and right children's parent wires are

// left_wire and right_wire, respectively

let left_child = GarbledNode::garble(*left, Some(left_wire.clone()), input_wires);

let right_child = GarbledNode::garble(*right, Some(right_wire.clone()), input_wires);

We then set the new node’s children to be the newly constructed children:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Set our children to the left and right children we just created

if let Some(ref left_c) = left_child {

out_node.borrow_mut().left = Some(left_c.clone());

out_node.borrow_mut().left_wire = Some(left_wire);

}

if let Some(ref right_c) = right_child {

out_node.borrow_mut().right = Some(right_c.clone());

out_node.borrow_mut().right_wire = Some(right_wire);

}

Finally, we call the assign_ciphertexts function on the new node, and output it:

1

2

3

4

// Create the ciphertexts for this node

out_node.borrow_mut().assign_ciphertexts();

Some(Rc::new(RefCell::new(GarbledNode::Gate(out_node))))

The assign_ciphertexts function assigns the gate its ciphertexts based on the wires connected to it. It starts by computing which of the output wire’s keys correspond to which bits in the operation (recall that gates’ operations are represented as 4-bit integers, which are the values in the gate’s truth table output read from bottom to top):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

impl GarbledGate {

/// Assign ciphertexts to this gate based on its encrypted inputs

fn assign_ciphertexts(&mut self) {

let op = self.op.unwrap();

// Get the bits of the operation

let vals = ((op & 1) != 0, (op & 2) != 0, (op & 4) != 0, (op & 8) != 0);

// Encrypt the output wire's keys

let out_on_key = self.parent_wire.as_ref().unwrap().on_key;

let out_off_key = self.parent_wire.as_ref().unwrap().off_key;

// Each bit in the operation determines whether we encrypt the output wire's on key or off key

let (out_00, out_01, out_10, out_11) = (

if vals.0 { out_on_key } else { out_off_key },

if vals.1 { out_on_key } else { out_off_key },

if vals.2 { out_on_key } else { out_off_key },

if vals.3 { out_on_key } else { out_off_key },

);

...

}

...

}

For example, if vals.2 is true, the gate outputs true if the left input is true and the right input is false (index 0b10=2), and so we’ll need to encrypt the on key of the output wire. Afterwards, we construct 4 ciphers based on the keys of the left and right children:

1

2

3

4

let left_off_cipher = AesCtr::new(&self.left_wire.as_ref().unwrap().off_key);

let left_on_cipher = AesCtr::new(&self.left_wire.as_ref().unwrap().on_key);

let right_off_cipher = AesCtr::new(&self.right_wire.as_ref().unwrap().off_key);

let right_on_cipher = AesCtr::new(&self.right_wire.as_ref().unwrap().on_key);

With each (left_X, right_Y) pair of the ciphers, we encrypt the corresponding output wire key (before the encryption we append zeros to allow the receiver to distinguish correctly decrypted ciphertexts, as mentioned earlier):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

// We append zeros to the ciphertexts so that the receiver will be able

// to distinguish between valid decryptions and gibberish

// (since the decrypted keys are, by definition, random sequences of bytes, indistinguishable from gibberish)

let zeros = [0u8; KEY_SIZE];

self.c_00 = Some(left_off_cipher.encrypt(

&right_off_cipher.encrypt([out_00, zeros].as_flattened(), 0),

0,

));

self.c_01 = Some(left_off_cipher.encrypt(

&right_on_cipher.encrypt([out_01, zeros].as_flattened(), 0),

0,

));

self.c_10 = Some(left_on_cipher.encrypt(

&right_off_cipher.encrypt([out_10, zeros].as_flattened(), 0),

0,

));

self.c_11 = Some(left_on_cipher.encrypt(

&right_on_cipher.encrypt([out_11, zeros].as_flattened(), 0),

0,

));

That’s it for the garbling algorithm! Now, let’s write the code for the garbler and the receiver. To allow them to exchange serialized structs over the network, we’ll use the protobuf API we developed in my previous post about writing an elliptic curve-based secure chat.

Garbler & Receiver

The garbler begins by asking for an input net worth (the argument to the circuit), and starting a TcpListener on a host and port specified in the command line arguments:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

fn get_net_worth() -> usize {

let mut input = String::new();

print!("How much $ do you have? (in millions): ");

stdout().flush().unwrap();

stdin().read_line(&mut input).expect("Failed to read line");

input = input.trim().to_lowercase();

input.parse::<usize>().unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let net_worth = get_net_worth();

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

let (ip, port) = (

args.get(1).unwrap(),

args.get(2).unwrap().parse::<u16>().unwrap(),

);

// Start the garbling server

listen(net_worth, (ip.to_string(), port)).unwrap();

}

Most of the interesting stuff is in the listen function. The receiver’s side is mostly the same, except it connects to the garbler instead of starting a server:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

fn get_net_worth() -> usize {

let mut input = String::new();

print!("How much $ do you have? (in millions): ");

stdout().flush().unwrap();

stdin().read_line(&mut input).expect("Failed to read line");

input = input.trim().to_lowercase();

input.parse::<usize>().unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let net_worth = get_net_worth();

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

let (ip, port) = (

args.get(1).unwrap(),

args.get(2).unwrap().parse::<u16>().unwrap(),

);

connect(net_worth, (ip.to_string(), port)).unwrap();

}

In the listen function, the garbler starts by calling the function construct_circuit to construct the comparator circuit:

1

2

3

4

5

fn listen(net_worth: usize, params: (String, u16)) -> Result<bool, io::Error> {

let listener = TcpListener::bind(format!("{}:{}", params.0, params.1)).unwrap();

let circuit = construct_circuit(10);

...

This function takes in a number n, and constructs a comparator circuit that, given the bits of two n-bit numbers x and y returns true if and only if x > y. In the next section, we’ll take a detour and such a circuit is constructed.

Constructing a Digital Comparator

The circuit is based on comparing the bits of the inputs one by one, starting from the MSB. For example, if the input size is 4 bits, given the inputs A = 0b1010 and B = 0b1011, we’ll want our circuit to do something like the following:

- Compare the MSBs: 1=1, and so we continue to the next bit

- Compare the second-most-significant bits: 0=0, so continue to the next bit

- Compare the third-most-significant bits: 1=1, so continue

- Compare the LSBs: 1 > 0, so B is greater than A

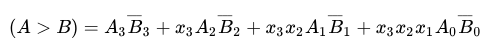

But how do we actually implement this using circuits? Well, for starters, we’ll need some way to check equality. To construct this, we’ll use XOR – since the XOR gate outputs true if and only if its two inputs are different, by negating XOR (i.e. XNOR), we can create a gate that outputs true if and only if its inputs are equal. For each index 0 <= i < n, we’ll denote with x_i the result of A_i XNOR B_i. Now, to check whether a single bit A_i is greater than another bit B_i, we can simply compute A_i AND (NOT B_i), since the only configuration in which A_i > B_i is when A_i = 1 and B_i = 0. Piecing together these two components, we can compare the two 4-bit numbers by first comparing the MSBs (A_3 AND (NOT B_3)), then checking whether the MSBs are equal and the second-most-significant bit of A is greater than that of B (x_3 AND A_2 AND (NOT B_2)), and so on, resulting in the following formula (taken from Wikipedia):

Implementing this in Rust is pretty straightforward, but one point we need to pay attention to is to correctly represent the gates as 4-bit numbers:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

const AND_GATE: u8 = 0b1000u8;

const OR_GATE: u8 = 0b1110u8;

const XNOR_GATE: u8 = 0b1001u8;

/// $x \wedge \neg y$

/// Truth table (top to bottom):

/// F F T F

const MY_GATE: u8 = 0b0100u8;

/// Construct a digital comparison circuit

/// where each input is of size n bits

pub fn construct_circuit(n: usize) -> GarbledCircuit {

let a_vals: Vec<circuit::Node> = (0..n).map(circuit::Node::Input).collect();

let b_vals: Vec<circuit::Node> = (0..n).map(|i| circuit::Node::Input(n + i)).collect();

let xs: Vec<circuit::Node> = (0..n).map(|i| circuit::Node::Gate(XNOR_GATE, Box::new(a_vals[i].clone()), Box::new(b_vals[i].clone()))).collect();

let mut out: Option<circuit::Node> = None;

for i in (0..n).rev() {

let mut cmp_hat = circuit::Node::Gate(MY_GATE, Box::new(a_vals[i].clone()), Box::new(b_vals[i].clone()));

for x in xs.iter().take(n).skip(i+1) {

cmp_hat = circuit::Node::Gate(AND_GATE, Box::new(cmp_hat.clone()), Box::new(x.clone()));

}

if out.is_some() {

out = Some(circuit::Node::Gate(OR_GATE, Box::new(out.unwrap().clone()), Box::new(cmp_hat.clone())));

} else {

out = Some(cmp_hat);

}

}

let circuit = Circuit::new(out.unwrap());

circuit.into()

}

In the outer for loop, we construct the individual conjugations seen in the formula, and then we set out to be a disjunction of the current value of out and the newly-constructed conjunction.

Key Exchange

Given the garbled circuit we constructed in the previous step, for the receiver to be able to evaluate the circuit, we need to do three things:

- Send the receiver the circuit

- Send the receiver our keys

- Send the receiver its keys using OT

Sending The Circuit

Let’s start with step 1 (this code is from the listen function in the garbler):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

let input_keys = circuit.input_keys();

if let Some(stream) = listener.incoming().next() {

let mut stream = stream.unwrap();

// Send the client the circuit

send_garbled_circuit(&mut stream, circuit.clone())?;

...

}

The send_garbled_circuit function needs to send the receiver the circuit’s structure and ciphertexts for each gate, but discard the keys. To do so, we introduce a new struct GarbledCircuitRecv:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

/// From the receiver's POV, a gate is defined by its ciphertexts and its children

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct GarbledGateRecv {

c_00: Option<Vec<u8>>,

c_01: Option<Vec<u8>>,

c_10: Option<Vec<u8>>,

c_11: Option<Vec<u8>>,

pub left: Option<Rc<RefCell<GarbledNodeRecv>>>,

pub right: Option<Rc<RefCell<GarbledNodeRecv>>>,

}

/// A node in the circuit can be either an input or a gate (like `Circuit` and `GarbledCircuit`)

#[derive(Clone)]

pub enum GarbledNodeRecv {

Input(usize),

Gate(GarbledGateRecv),

}

/// A garbled circuit from the receiver's POV

pub struct GarbledCircuitRecv {

pub(crate) out: GarbledNodeRecv,

pub(crate) n: usize,

}

This struct is very similar to GarbledCircuit, except it doesn’t store information about the keys. Converting from a GarbledCircuit to a GarbledCircuitRecv is trivial, since the only thing we need to do is discard some of the fields:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

impl From<GarbledCircuitSend> for GarbledCircuitRecv {

fn from(value: GarbledCircuitSend) -> Self {

let n = value.n as usize;

let out = value.out.unwrap().into();

GarbledCircuitRecv { out, n }

}

}

// Used by the garbler to "dumb down" garbled nodes into a form the receiver can understand

impl From<GarbledNode> for GarbledNodeRecv {

fn from(value: GarbledNode) -> Self {

match value {

GarbledNode::Input(idx) => GarbledNodeRecv::Input(idx),

GarbledNode::Gate(gate) => {

let gate = gate.borrow().clone();

GarbledNodeRecv::Gate(GarbledGateRecv {

c_00: Some(gate.c_00()),

c_01: Some(gate.c_01()),

c_10: Some(gate.c_10()),

c_11: Some(gate.c_11()),

left: Some(Rc::new(RefCell::new(

gate.left.clone().unwrap().borrow().clone().into(),

))),

right: Some(Rc::new(RefCell::new(

gate.right.clone().unwrap().borrow().clone().into(),

))),

})

}

}

}

}

impl From<GarbledCircuit> for GarbledCircuitRecv {

fn from(value: GarbledCircuit) -> Self {

GarbledCircuitRecv {

out: value.out().into(),

n: value.n(),

}

}

}

Then, in send_garbled_circuit, we simply convert our garbled circuit into a GarbledCircuitRecv and serialize it using the GarbledCircuitSend and GarbledNodeSend protobufs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

/// Send the garbled circuit to the receiver

pub fn send_garbled_circuit(

stream: &mut TcpStream,

garbled_circuit: GarbledCircuit,

) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

let n = garbled_circuit.n();

// "dumb down" the circuit to a form the receiver can understand

let recv_circuit: GarbledCircuitRecv = garbled_circuit.into();

let out_msg: GarbledNodeSend = recv_circuit.out.into();

// Send the garbled circuit to the receiver

let mut garbled_circuit_msg = GarbledCircuitSend::new();

garbled_circuit_msg.n = n as i64;

garbled_circuit_msg.out = MessageField::some(out_msg);

MessageStream::<GarbledCircuitSend>::send_msg(stream, garbled_circuit_msg)?;

Ok(())

}

These protobufs are defined as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

message Input {

// The input's index

int64 idx = 1;

}

message Gate {

// The gate's ciphertexts

bytes c_00 = 1;

bytes c_01 = 2;

bytes c_10 = 3;

bytes c_11 = 4;

// The gate's children

GarbledNodeSend left = 5;

GarbledNodeSend right = 6;

}

message GarbledNodeSend {

// An input node

optional Input input = 1;

// A gate

optional Gate gate = 2;

}

message GarbledCircuitSend {

// The output gate

GarbledNodeSend out = 1;

// The number of inputs to the circuit

int64 n = 2;

}

Converting from a GarbledCircuitRecv to a GarbledCircuitSend is a pretty menial task and not that interesting (the gist of it is that we copy the corresponding fields and recursively call the conversion function on the children, until we get to an Input node), so I won’t list the code here. On the receiver’s side, we parse the circuit as follows:

1

2

3

4

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(format!("{}:{}", params.0, params.1))?;

// The garbler should have sent us the garbled circuit

let circuit = MessageStream::<GarbledCircuitSend>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

let circuit_recv: GarbledCircuitRecv = circuit.into();

Sending The Receiver The Garbler’s Keys

The next thing we need to do is send the receiver the garbler’s keys. These are the keys of the first n input wires (the other n correspond to the receiver’s keys). This is done using the send_input_keys function (called from the garbler’s listen function):

1

2

3

4

let input_keys = circuit.input_keys();

// Send the receiver our input keys

send_input_keys(&mut stream, &circuit, net_worth)?;

The send_input_keys function iterates over the bits of the garbler’s net worth, and, based on the value of the bit, appends the corresponding key to the vector keys:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

pub fn send_input_keys(

stream: &mut TcpStream,

circuit: &GarbledCircuit,

net_worth: usize,

) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

// Extract the keys we need to send based on the garbler's net worth

let mut keys = vec![];

let key_map = circuit.input_keys();

for key_idx in 0..circuit.n() / 2 {

let wire = key_map.get(&key_idx).unwrap();

keys.push(

// Is the current bit set or not?

if (net_worth & (1 << key_idx)) != 0 {

wire.on_key().to_vec()

} else {

wire.off_key().to_vec()

},

);

}

...

}

We then send these keys to the receiver using the GarblerKeys protobuf:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let mut keys_msg = GarblerKeys::new();

keys_msg.keys = keys;

MessageStream::<GarblerKeys>::send_msg(stream, keys_msg)?;

Ok(())

This protobuf is defined as follows:

1

2

3

4

// The garbler sends the receiver the garbler's input keys

message GarblerKeys {

repeated bytes keys = 1;

}

Parsing this on the receiver’s side is very simple:

1

2

3

// What are the garbler's keys in the circuit?

let keys_msg = MessageStream::<GarblerKeys>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

let mut circuit_inputs = keys_msg.keys;

Sending The Receiver The Receiver’s Keys

Next, we need to send the receiver the keys corresponding to its net worth using OT (so that the garbler won’t find out the bits of the receiver’s net worth). To do so, the garbler first generates an RSA keypair, and sends the public key over to the receiver using the RsaPubkey protobuf:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

let keypair = Keypair::new(None, None);

println!("Keypair generated");

...

if let Some(stream) = listener.incoming().next() {

...

// Send the receiver our RSA public key

let mut pubkey_msg = RsaPubkey::new();

pubkey_msg.e = keypair.public.e.to_bytes_be();

pubkey_msg.n = keypair.public.n.to_bytes_be();

MessageStream::<RsaPubkey>::send_msg(&mut stream, pubkey_msg)?;

...

}

...

The RsaPubkey protobuf contains the public key’s modulus and exponent:

1

2

3

4

5

// An RSA public key; needed for the oblivious transfer

message RsaPubkey {

bytes n = 1;

bytes e = 2;

}

The receiver parses this as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

let garbler_pubkey = MessageStream::<RsaPubkey>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

let pubkey = PublicKey {

e: BigUint::from_bytes_be(&garbler_pubkey.e),

n: BigUint::from_bytes_be(&garbler_pubkey.n),

};

The garbler and the receiver then engage in n rounds of OT, where in each round one key is transmitted to the receiver. Each round starts with the garbler constructing a new ObTransferSender based on the keys of the current wire:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

for i in circuit.n() / 2..circuit.n() {

let wire = input_keys.get(&i).unwrap();

let msgs = (

BigUint::from_bytes_be(&wire.off_key()),

BigUint::from_bytes_be(&wire.on_key()),

);

let sender = ObTransferSender::new(msgs, keypair.clone());

...

}

The garbler sends the x values of the ObTransferSender to the receiver:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

/

*

Xs is defined as follows:

message Xs {

bytes x_0 = 1;

bytes x_1 = 2;

}

*/

let mut xs = Xs::new();

let xs_bigints = sender.xs();

xs.x_0 = xs_bigints.0.to_bytes_be();

xs.x_1 = xs_bigints.1.to_bytes_be();

MessageStream::<Xs>::send_msg(&mut stream, xs)?;

The receiver parses this and constructs an ObTransferReceiver as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

for i in 0..n / 2 {

let xs = MessageStream::<Xs>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

let (x_0, x_1) = (

BigUint::from_bytes_be(&xs.x_0),

BigUint::from_bytes_be(&xs.x_1),

);

let receiver = ObTransferReceiver::new(pubkey.clone(), (x_0, x_1));

...

}

Next, the receiver chooses the current bit of the receiver’s net worth as the message index, blinds it, and sends the result to the sender:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

/

* OtBlindedIdx is defined as follows:

message OtBlindedIdx {

bytes v = 1;

}

*/

let curr_bit = ((net_worth & (1 << i)) != 0) as usize;

// Blind the index we want & send it to the garbler

let v = receiver.blind_idx(curr_bit);

let mut blinded_idx = OtBlindedIdx::new();

blinded_idx.v = v.to_bytes_be();

MessageStream::<OtBlindedIdx>::send_msg(&mut stream, blinded_idx)?;

The garbler parses this, generates the combined messages (m’_0 and m’_1), and sends them to the receiver:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

/

* OtEncMessages:

message OtEncMessages {

bytes m_prime_0 = 1;

bytes m_prime_1 = 2;

}

*/

// Receive the blinded index from the message

let blinded_idx = MessageStream::<OtBlindedIdx>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

// Respond with the m_primes

let m_primes = sender.gen_combined(BigUint::from_bytes_be(&blinded_idx.v));

let mut m_primes_msg = OtEncMessages::new();

m_primes_msg.m_prime_0 = m_primes.0.to_bytes_be();

m_primes_msg.m_prime_1 = m_primes.1.to_bytes_be();

MessageStream::<OtEncMessages>::send_msg(&mut stream, m_primes_msg)?;

Finally, the receiver derives the desired key from these two messages, and appends it to the circuit_inputs vector (which previously contained only the garbler’s keys):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

let m_primes_msg = MessageStream::<OtEncMessages>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

let (m_prime_0, m_prime_1) = (

BigUint::from_bytes_be(&m_primes_msg.m_prime_0),

BigUint::from_bytes_be(&m_primes_msg.m_prime_1),

);

// Get our key

circuit_inputs.push(

receiver

.derive_msg((m_prime_0, m_prime_1), curr_bit)

.to_bytes_be(),

);

Awesome! At this point, the receiver has all of the keys needed to evaluate the circuit.

Evaluating The Circuit

To evaluate the circuit, we implement the eval function on GarbledCircuitRecv. This function starts by matching on the type of node – if the node is an Input node, it simply returns the input at the corresponding index:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

impl GarbledNodeRecv {

/// Evaluate the garbled circuit based on a vector of input keys

pub fn eval(&self, inputs: &Vec<[u8; KEY_SIZE]>) -> [u8; KEY_SIZE] {

match self {

Self::Input(idx) => inputs[*idx],

...

}

}

}

Otherwise, if the node is a gate, we recursively call eval on the gate’s left and right children, and construct two ciphers from their outputs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Self::Gate(gate) => {

// Construct ciphers based on the keys coming from our left and right children

// (this is done by recursively calling `eval` on our children)

let left_out = gate.left.as_ref().unwrap().borrow().eval(inputs);

let right_out = gate.right.as_ref().unwrap().borrow().eval(inputs);

let left_cipher = AesCtr::new(&left_out);

let right_cipher = AesCtr::new(&right_out);

...

}

We then decrypt all of the gate’s 4 ciphertexts, returning the one that ends with the zero suffix:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

// The correct key is appended with 32 zeros

let suffix = [0u8; KEY_SIZE];

// Decrypt each of this gate's ciphertexts based on the two ciphers we constructed

// Only one decryption will be valid

let d_00 =

right_cipher.decrypt(&left_cipher.decrypt(gate.c_00.as_ref().unwrap(), 0), 0);

let d_01 =

right_cipher.decrypt(&left_cipher.decrypt(gate.c_01.as_ref().unwrap(), 0), 0);

let d_10 =

right_cipher.decrypt(&left_cipher.decrypt(gate.c_10.as_ref().unwrap(), 0), 0);

let d_11 =

right_cipher.decrypt(&left_cipher.decrypt(gate.c_11.as_ref().unwrap(), 0), 0);

// Get this gate's output key by checking which decryption ends with the correct suffix

if d_00.ends_with(&suffix) {

d_00[0..KEY_SIZE].try_into().unwrap()

} else if d_01.ends_with(&suffix) {

d_01[0..KEY_SIZE].try_into().unwrap()

} else if d_10.ends_with(&suffix) {

d_10[0..KEY_SIZE].try_into().unwrap()

} else {

d_11[0..KEY_SIZE].try_into().unwrap()

}

On the receiver’s side, evaluating the garbled circuit with the input keys looks as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// Evaluate the garbled circuit

let circuit_inputs: Vec<[u8; 32]> = circuit_inputs

.iter()

.map(|x| x.as_slice().try_into().unwrap())

.collect();

let result = circuit_recv.eval(&circuit_inputs);

The receiver then constructs a final protobuf, EvalResult, that contains whether the gate returned true or false, and sends it to the garbler (also printing the result):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

/

* EvalResult:

message EvalResult {

bool result = 1;

}

*/

// Evaluate the garbled circuit

// Send the result to the garbler

let mut msg = EvalResult::new();

msg.result = result[0] != 0;

MessageStream::<EvalResult>::send_msg(&mut stream, msg)?;

// Print the result

if result[0] != 0 {

println!("The garbler is richer!");

} else {

println!("The receiver is richer!");

}

Ok(true)

The garbler parses this as follows, and also prints the result:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let result = MessageStream::<EvalResult>::receive_msg(&mut stream)?;

if result.result {

println!("The garbler is richer!");

} else {

println!("The receiver is richer!");

}

That’s it! We finished implementing a garbled circuits-based solution to the millionaires’ problem from scratch! In the next section, we’ll do a short demo, and then conclude.

Demo

For the demo, we’ll run the algorithm a few times with varying wealth:

Cool! As we can see, the correct answer is printed for each pair of wealths, both on the garbler’s and the receiver’s side.

Conclusion

In this post, we solved the Millionaires’ problem in Rust. To do this, we had to construct a digital comparison circuit using a boolean circuit API, and then garble it using the circuit garbling algorithm. Along the way, to perform key exchange, we also learned about Oblivious Transfer, how it works, and its applications. I find it incredible that such a seemingly-impossible problem has a solution. What’s more, due to the expressivity of boolean circuits, we can evaluate much more complex functions. An interesting direction for a future post would be privately evaluating a neural network that takes in inputs for two parties (e.g. in a federated learning setup). To do this, we’d have to extend our existing algorithm to handle floating-point values and evaluate the nonlinearities in the network (e.g. ReLUs). Since the resulting circuit scales very fast with the size of the model, we’d also need to find ways to optimize the circuit. Another interesting topic for a future post would be evaluating functions that take in inputs from more than 2 parties (e.g. compute max(x_1, …, x_N) for N > 2). The algorithms in that case would be more complicated – for one party to be able to evaluate the circuit, it would need to get the keys of all parties, which can’t be done with the 1-2 OT algorithm used in this post. All of these directions may be covered in a future post. The code for this post is available here.

Thanks for reading! Yoray