Making a Secure Chat in Rust

Prelude

Hello! Today, we are going to make a secure chat in Rust. “Secure” means that we don’t want attackers/eavesdroppers to be able to find out the contents of our messages (privacy), and we also want to make sure that we know who we’re talking to on the other side (authentication). To do this, we are going to use some common cryptographical concepts. I’ll explain all the cryptographical concepts we’ll use, so you don’t have to know anything about crypto before reading this. The only math prerequisite is Finite Fields. Note: This project came out quite long (~1200 LOC), so not all of the code is included in the post. For the full project, you can check out the git repo: https://github.com/vaktibabat/securechat

Warning

For a post about implementing crypto from scratch, this might seem like a weird start, but you should never roll your own crypto! There are several reasons for this:

- When writing crypto code, a LOT of things, some of which are very subtle, can go wrong. For example, custom implementations can be vulnerable to side-channel attacks, such as timing attacks or power analysis, which make theoretically secure schemes insecure.

- It is very easy to fall into a false sense of security

- Unlike popular libraries such as OpenSSL, homebrew crypto isn’t time-tested (OpenSSL for example exists for 26 years at the time of writing), and hasn’t been reviewed by many people and experts Despite the previous reasons, the reason I’m working on this project is because I wanted to learn more about crypto, and I believe that implementing stuff is a very very good way to learn. This project really forced me to understand all the different algorithms, and also how to implement a custom (although fairly basic) protocol on top of TCP.

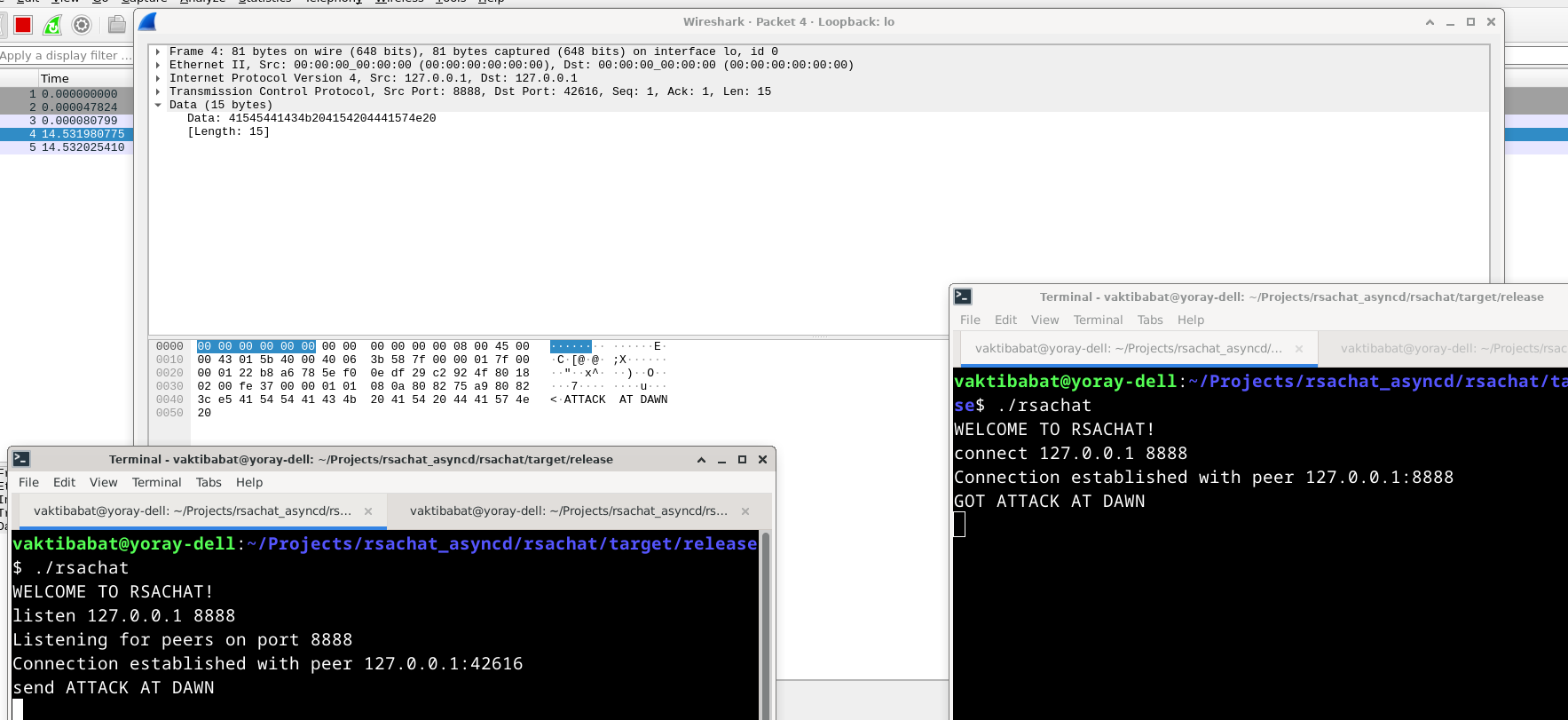

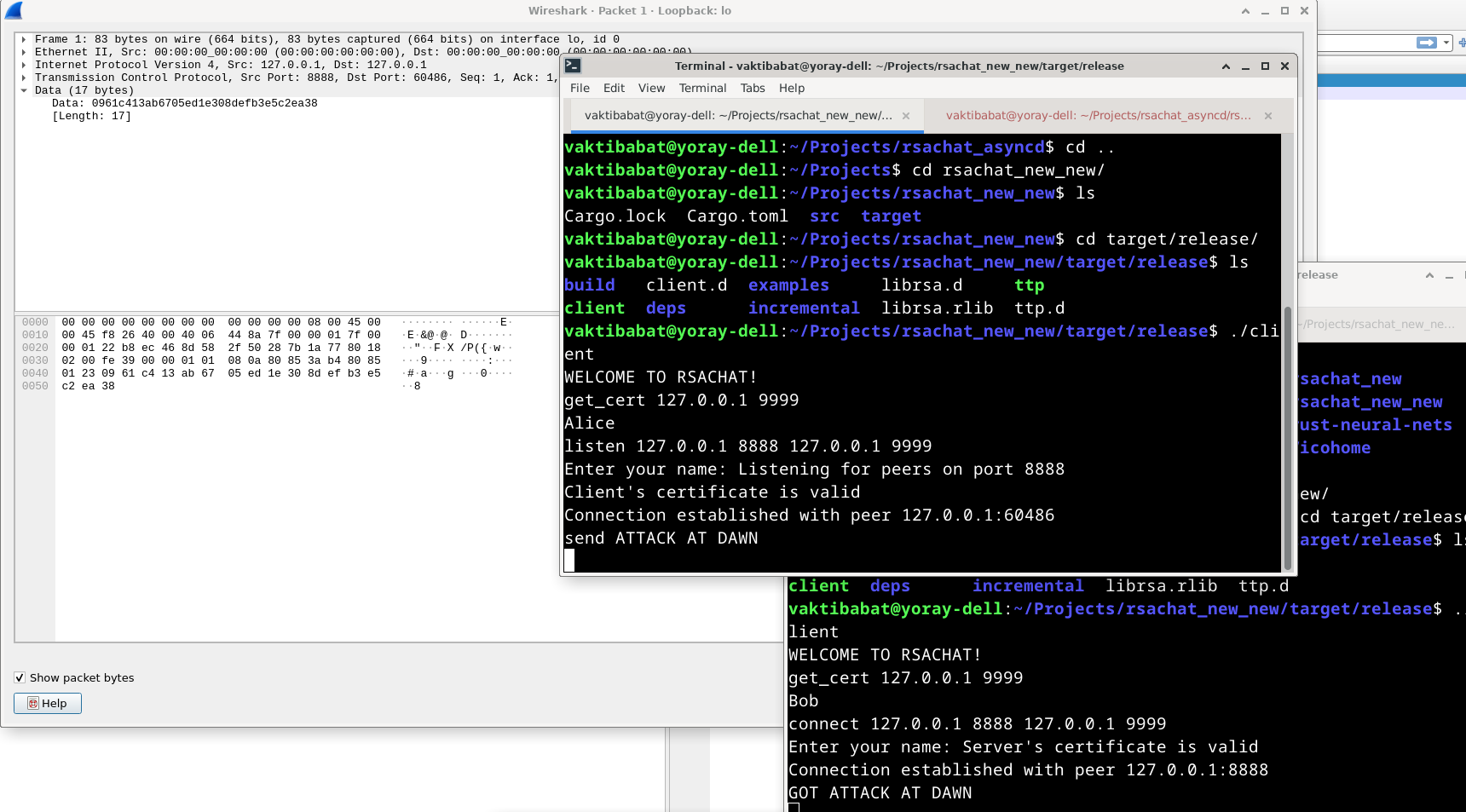

A simple client/server chat

Before implementing the “secure” part, we need to have the “chat” part. To do this, I wrote a very basic TCP chat using Rust and the tokio library: One side listens, the other side connects, messages are exchanged between the two sides using write() and read(), and everyone’s happy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

async fn peer_loop(stream: &mut TcpStream) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

println!("Connection established with peer {}", stream.peer_addr().unwrap());

let (mut reader, mut writer) = stream.split();

loop {

let stdin = io::stdin();

let br = BufReader::new(stdin);

let mut lines = br.lines();

let mut msg = [0u8; 100];

select! {

line = lines.next_line() => {

if let Some(cmd_str) = line.unwrap() {

let cmd = parse_cmd(cmd_str.split(' ').map(|s| s.trim()).collect());

match cmd.op {

Opcode::Help => help(),

Opcode::Connect => println!("Please leave your current connection before connecting to another peer."),

Opcode::Send => handle_send(cmd, &mut writer).await?,

Opcode::Leave => break,

Opcode::Quit => std::process::exit(0),

Opcode::Listen => println!("Please leave your current connecting before listening for a new peer."),

Opcode::Unknown => println!("Unknown opcode. Please use help."),

}

}

}

_ = reader.read(&mut msg) => {

println!("GOT {}", String::from_utf8(msg.to_vec()).unwrap());

}

}

}

Ok(())

}

async fn handle_connect(cmd: Command) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

let host = &cmd.args[0];

let port = cmd.args[1].parse::<u16>().expect("Invalid Port");

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(format!("{}:{}", host, port)).await?;

peer_loop(&mut stream).await?;

Ok(())

}

async fn handle_send(cmd: Command, writer: &mut WriteHalf<'_>) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

// To reduce the amount of TCP stream writes, we first concatanate the arguments to a new string

let mut final_str = String::new();

// Each argument is considered a word. We seperate them with spaces

for word in cmd.args {

final_str.push_str(&word);

final_str.push(' ');

}

writer.write(final_str.as_bytes()).await?;

Ok(())

}

async fn handle_listen(cmd: Command) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

let host = &cmd.args[0]

let port = cmd.args[1].parse::<u16>().expect("Not a valid port");

println!("Listening for peers on port {}", port);

let listener = TcpListener::bind(format!("{}:{}", host, port))

.await?;

let (mut stream, _) = listener.accept().await?;

peer_loop(&mut stream).await?;

Ok(())

}

The Command type is used to parse incoming commands from stdin, and is not shown here to keep the code short. This chat is insecure because attackers can see all of the messages in plaintext using a MITM attack, such as ARP poisoning. Let’s demonstrate this by inspecting the network traffic with Wireshark:  We can entirely see the message (“ATTACK AT DAWN”) in the data of the TCP packet!

We can entirely see the message (“ATTACK AT DAWN”) in the data of the TCP packet!

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Cryptography

Cryptographic systems can be divided into two main classes: Symmetric Cryptography and Asymmetric Cryptography.

Symmetric Cryptography

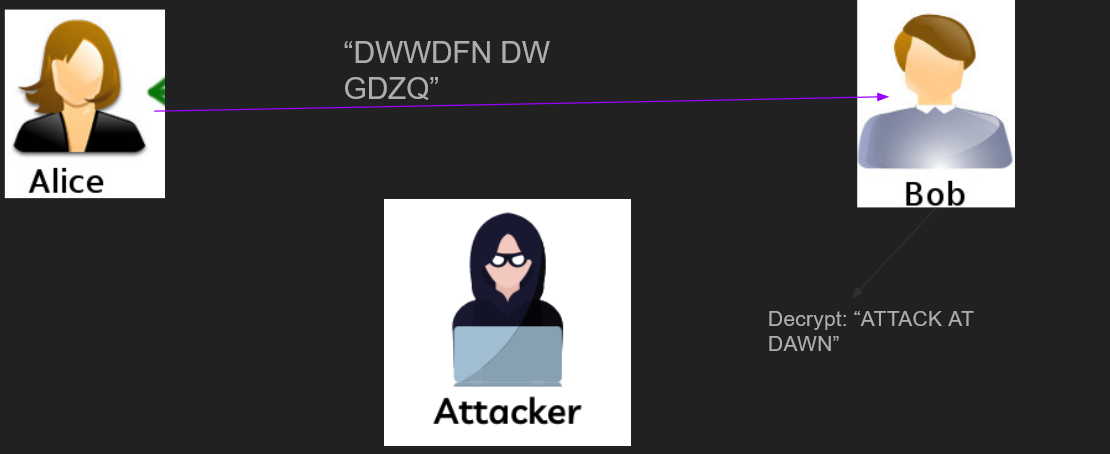

In symmetric systems, two users who want to talk to each other, call them Alice and Bob, have a shared symmetric key, which they use to encrypt and decrypt messages. Decryption is the inverse operation to encryption: It takes in a ciphertext (the encrypted message) and returns the original message (also referred to as the plaintext). Symmetric Cryptography presents a challenge: How do we transmit the symmetric key? After all, we can’t transmit it over the insecure channel, because then the attacker will also get the key. There are several solutions to this problem:

- Transmit the symmetric key through some secure OOB (out-of-band) channel, such as carrier mail. After this, Alice and Bob can talk over the insecure channel using the key.

- Use asymmetric cryptography (see the next section) An example of a symmetric system is a shift cipher (such as Ceaser’s cipher): the shift amount is the secret key. In the following figure, the shift amount is 3.

Of course, the shift cipher is very insecure, since the space of all possible keys is extremely small: 25 (because there are 26 letters in the English alphabet). The most common symmetric encryption algorithm today is AES, which is also used in the secure chat. The key sizes of AES are 128 bit, 192 bit, and 256 bit, which is much more secure than the key size of the shift cipher. The number of possible keys (the keyspace) is so big large 2^256, the number of possible keys in 256-bit AES is almost the number of atoms in the observable universe.

Of course, the shift cipher is very insecure, since the space of all possible keys is extremely small: 25 (because there are 26 letters in the English alphabet). The most common symmetric encryption algorithm today is AES, which is also used in the secure chat. The key sizes of AES are 128 bit, 192 bit, and 256 bit, which is much more secure than the key size of the shift cipher. The number of possible keys (the keyspace) is so big large 2^256, the number of possible keys in 256-bit AES is almost the number of atoms in the observable universe.Asymmetric Cryptography

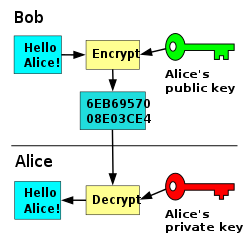

As we saw earlier, a central problem in symmetric systems is that in order to encrypt messages to a some, you need to somehow send a secret symmetric key to them. This key must be transmitted using a secure channel (otherwise it will not be secret), which takes more time, if it even is possible. The idea of asymmetric crypto was suggested by mathematicians Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman in a 1976 paper called “New Directions in Cryptography”. The main concept is this: Each person holds a public key, known to everyone, and a private key, which, as the name implies, is kept secret. Anyone can encrypt messages to you using your public key, but only you can decrypt them using your private key. This is similar to the concept of a mailbox: anyone can slide letters into your mailbox, but only you can open the mailbox with your key and read the letters. Most asymmetric algorithms are based on the concept of one-way functions: functions that are computationally easy to compute in one direction, but are computationally infeasible to compute in the other direction. The most commonly used asymmetric cryptosystems are RSA (based on the integer factoring problem. This is the algorithm used in the chat), Diffie-Hellman (based on the discrete log problem), and elliptic curve discrete logarithm (ECDL). An example is shown in the following figure:

Photo Taken from Wikipedia Public key algorithms are usually much slower than their symmetric counterparts, so we usually only encrypt a symmetric key using the public key algorithm, and then encrypt all the following messages using the symmetric key:

Photo Taken from Wikipedia Public key algorithms are usually much slower than their symmetric counterparts, so we usually only encrypt a symmetric key using the public key algorithm, and then encrypt all the following messages using the symmetric key:- Bob generates some symmetric key K

- Bob encrypts K using Alice’s public key PUB_A and gets the result K1

- Bob sends K1 to Alice

- Alice decrypts K1 using her private key PRI_A, and gets K

- Alice and Bob exchange messages using K Another important capability of asymmetric cryptography is signing messages. For example, consider a bank that processes transactions of the form “transfer $X from person A to person B”. If the bank doesn’t validate the identity of the users, Bob could send a transaction of the form “transfer $10000 from Alice to Bob”, and the bank wouldn’t have any way to validate that this transaction is from Bob and not from Alice. With signatures, Alice and Bob could sign their transactions using their private keys. The bank can then validate the signatures using the public keys, and accept/reject the transactions based on the validity of the signature

The Architecture of Our Chat

Now, let’s make the chat. Because we do not have a secure channel to use, we will use asymmetric cryptography.

- Each user has a keypair (a public key and a private key)

- The algorithm used is RSA

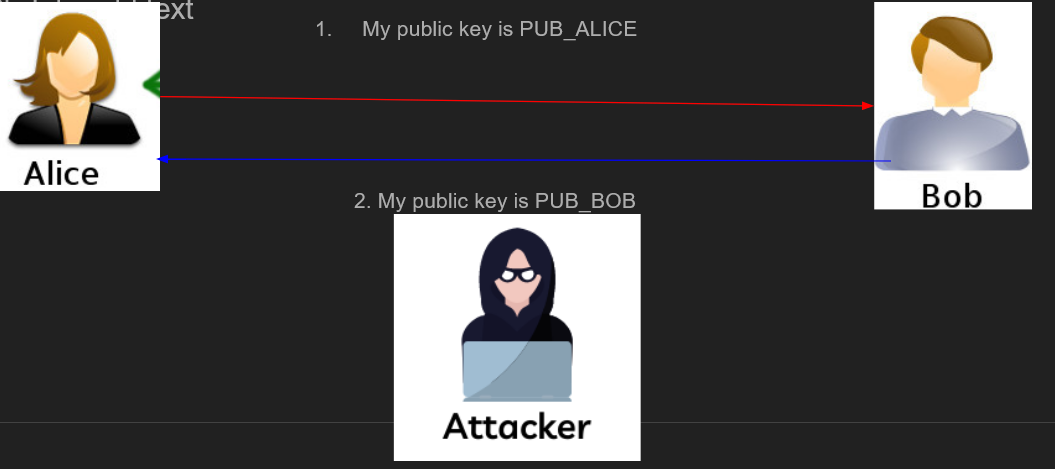

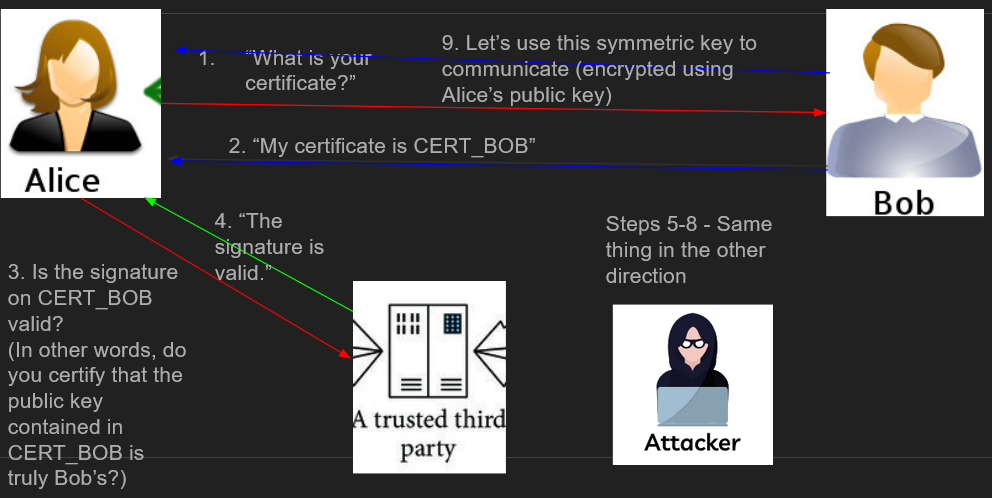

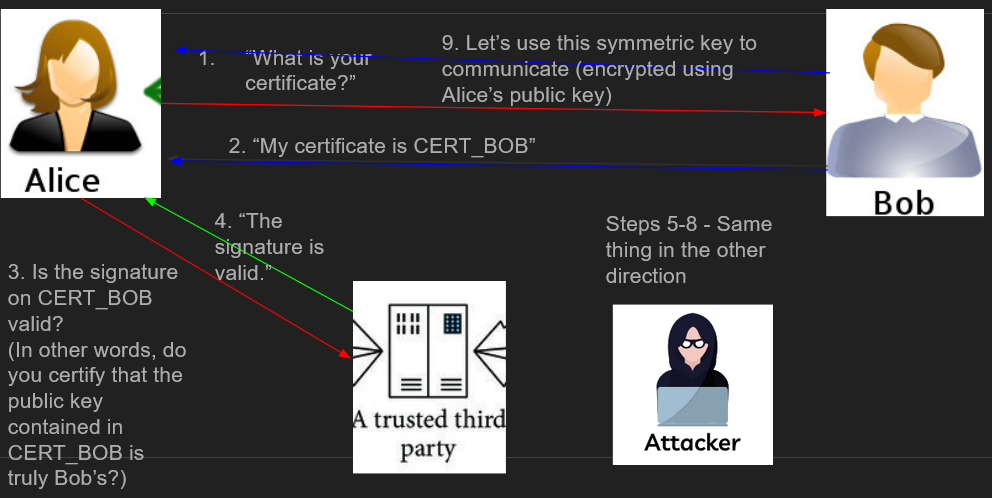

- In order to get better performance, we encrypt a symmetric key for 128-bit AES using RSA, and then encrypt/decrypt messages using the symmetric key, as discussed earlier We also need to exchange public keys between Alice and Bob somehow. A naïve approach would be to have Alice send her public key to Bob, and then have Bob send his public key to Alice:

Do you spot the problem here? The attacker can replace Alice’s public key PUB_ALICE with their own public key PUB_ATTACKER. The users are anonymous (Bob doesn’t know who he’s talking to on the other side), so from Bob’s perspective he got a perfectly valid public key, which he can use to encrypt messages to Alice. But once Bob will encrypt his secret message using the attacker’s public key and send it to Alice, the attacker will be able to decrypt the message using their private key. To solve this issue, we have several approaches:

Do you spot the problem here? The attacker can replace Alice’s public key PUB_ALICE with their own public key PUB_ATTACKER. The users are anonymous (Bob doesn’t know who he’s talking to on the other side), so from Bob’s perspective he got a perfectly valid public key, which he can use to encrypt messages to Alice. But once Bob will encrypt his secret message using the attacker’s public key and send it to Alice, the attacker will be able to decrypt the message using their private key. To solve this issue, we have several approaches: - Transmit the public keys over a secure channel (we don’t have one here, this is why we used asymmetric cryptography in the first place)

- Use a central key server that holds the public keys of all users along with their more information about them

- Use a Trusted Third Party (TTP) that users can use in order to validate the authenticity of the public keys they receive We’ll go with the third option. The TTP accomplishes its goal by signing the digest (output of a hash algorithm) of the public key and some information about the user, such as their name, address, etc. The public key, along with the extra information, is called the certificate. Other users can then verify the certificate against the TTP:

If the attacker were to perform a MITM attack and present his own certificate as Bob’s, the TTP would say that the signature is not valid (since the certificate is signed to the attacker and not to Bob), and so Alice would know not to transmit sensitive data to Bob. In our chat, we will only use the name as an extra identity, and the TTP will also sign all certificates, but in real applications, much more information will be used. The code for the TTP server is shown in the following listing:

If the attacker were to perform a MITM attack and present his own certificate as Bob’s, the TTP would say that the signature is not valid (since the certificate is signed to the attacker and not to Bob), and so Alice would know not to transmit sensitive data to Bob. In our chat, we will only use the name as an extra identity, and the TTP will also sign all certificates, but in real applications, much more information will be used. The code for the TTP server is shown in the following listing:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

struct Message {

op: MessageOpcode,

payload: Vec<u8>,

}

#[derive(Copy, Clone, PartialEq)]

enum MessageOpcode {

HandshakeStart,

CertificateShow,

RequestCertificate,

CertSigned,

ValidateCertificate,

ValidationResponse,

CertificateAccepted,

CertificateRejected,

Other,

}

/// Listen for connections

async fn ttp_server(ip: String, port: u16) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

let listener = TcpListener::bind(format!("{}:{}", ip, port)).await?;

// Create a keypair for the TTP

let ttp_keypair = Keypair::new(None, None);

let ttp_keypair_clone = ttp_keypair.clone();

println!("TTP Listening on {}:{}", ip, port);

loop {

let (mut socket, _) = listener.accept().await?;

let keypair_clone = ttp_keypair_clone.clone();

// Spawn an async task for each new connection

tokio::spawn(async move {

// receive_message() is a custom function used

// to receive Messages

let msg = socket

.receive_message()

.await

.expect("Failed to receive message");

// Get the payload

let payload = msg.payload;

match msg.op {

MessageOpcode::RequestCertificate => {

// Get the name length: 4 BE bytes

let name_length = u32::from_be_bytes(payload[0..4].try_into().unwrap());

// The name + the public key's n

let to_sign = &payload[4..4 + name_length as usize + 256];

// Calculate the MD5 digest

let digest = md5::compute(to_sign);

// Convert it to a BigUint and sign it using our private key

let signature = keypair_clone.sign(&BigUint::from_bytes_be(&digest.to_vec()));

// Respond to the client

let mut resp = Message {

op: MessageOpcode::CertSigned,

payload: signature.to_bytes_be(),

};

socket

.send_message(&mut resp)

.await

.expect("Failed to send response to client");

socket.shutdown().await.expect("Failed to shutdown socket");

}

MessageOpcode::ValidateCertificate => {

let name_length = u32::from_be_bytes(payload[0..4].try_into().unwrap());

// The signature is for the digest of this part

let signed_part = &payload[4..4 + name_length as usize + 256];

// The signature claimed by the certificate

let signature = &payload

[4 + name_length as usize + 256..4 + name_length as usize + 256 + 256];

// Calculate the MD5 digest

let digest = md5::compute(signed_part);

// Convert it to a BigUint and sign it using our private key

let is_signature_valid = keypair_clone.validate(

&BigUint::from_bytes_be(&digest.to_vec()),

&BigUint::from_bytes_be(signature),

);

// Respond to the client

// 1 means that the signature

// is valid, and 0 means that its not

let mut payload = vec![];

if is_signature_valid {

payload.push(1);

} else {

payload.push(0);

}

let mut resp = Message {

op: MessageOpcode::CertSigned,

payload,

};

socket

.send_message(&mut resp)

.await

.expect("Failed to send response to client");

socket.shutdown().await.expect("Failed to shutdown socket");

}

_ => println!("Unimplemented"),

}

});

}

}

To summarize the code:

- We define a custom Message type that represents custom messages

- If the server gets a message of type RequestCertificate, it parses the certificate according to the following format:

- First 4 bytes - Represent the name in big endian

- Next bytes represent the name

- Next, we have the public key (we’ll look at it more in detail later), which is 2048 bits

- The trusted third party signs the digest using MD5 (not a secure hashing algorithm), and responds with the signature

- To validate a certificate, the trusted third party parses the certificate, computes the digest, and then checks if the signature is authentic The client asks for a certificate using the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

// Represents a connection

pub struct Peer {

keypair: Keypair,

pub cert: Option<Certificate>,

pub stream: Option<TcpStream>,

pub cipher: Option<Aes128>, // The symmetric key

}

impl Peer {

...

/// Ask the TTP for a certificate

pub async fn get_cert(

&mut self,

host: &String,

port: u16,

name: String,

) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

// Connect to the TTP

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(format!("{}:{}", host, port)).await?;

let mut payload = vec![];

let name_len = name.len() as u32;

// Name Length: 4 BE bytes

payload.append(&mut name_len.to_be_bytes().to_vec());

// The name

payload.append(&mut name.as_bytes().to_vec());

// Public key's n

payload.append(&mut self.keypair.public.n.to_bytes_be());

// Construct a message

let mut msg = Message {

op: MessageOpcode::RequestCertificate,

payload,

};

// Send it

stream.send_message(&mut msg).await?;

// Read the response

let resp = stream.receive_message().await?;

// Cert has been succesfully signed

if resp.op == MessageOpcode::CertSigned {

self.cert = Some(Certificate {

name,

public: self.keypair.public.clone(),

signature: resp.payload,

})

} else {

return Err(io::Error::other("The TTP didn\'t sign the certificate"));

}

// Shutdown the stream

stream.shutdown().await?;

Ok(())

}

...

}

Certificates are used to secure nearly all of the traffic on the internet, using a protocol called TLS (Transport Layer Security). In order to use TLS, websites need to apply for a Certificate Signing Request (CSR) to a trusted third party, called a Certificate Authority. Many such CAs exist, and the public keys for the CAs are stored offline in many browsers and devices. This lets us validate certificates. When an attacker performs a MITM attack and impersonates a website, the browser lets us know that the certificate is invalid, and doesn’t let us connect unless we make an exception. If the CA were to be hacked (this has happened before: see https://www.enisa.europa.eu/media/news-items/operation-black-tulip/), an attacker could sign certificates of their own in order to impersonate websites, and browsers wouldn’t warn the user because the CAs are trusted. We now have the complete architecture of the chat:

- Each user has a keypair

- Users can ask the TTP to sign them a certificate

- When two users want to talk to each other, they validate the certificate of each other against the TTP

- RSA is used to exchange a symmetric key secretly

- The symmetric key is used to encrypt all actual messages using AES Now, let’s talk about the algorithms themselves

RSA

In 1977 (A year after Diffie and Hellman’s paper, which we talked about earlier), computer scientists Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman invented RSA (the algorithm is named after the surnames of its three inventors). RSA is based on the complexity of factoring large (very large: 2048 bits is the size recommended by NIST, the National Institute of Standards and Technology) integers into their prime factors. This is the one-way function: Multiplying two prime numbers to get a new composite number is computationally easy, but factoring the resulting composite number into the two original prime factors takes a long time if the numbers are sufficiently large. RSA works as follows:

- Pick two large primes p and q (for example 1024 bits long)

- Multiply p and q to get n = pq

- Compute Euler’s totient of n: phi(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1)

- Pick a public exponent e such that 1 < e < phi(n)

- Compute the modular inverse of e modulo phi(n) (this can be done efficiently using the Euclidean algorithm): this value is called d The public key is comprised of n and e, and the private key is comprised of p, q, and d.

- In order to encrypt a message m, we compute c = (m^e) mod n (Remember that e and n are public, so any user can do this)

- In order to decrypt the ciphertext c, we compute m = c^(d) mod n.

- To sign a message m, we calculate s = (m^d) mod n

- To verify a signature s for a message m, we check whether s^e mod n == m Why is decryption the inverse of encryption? Remember that d is chosen to be the modular inverse of e modulo phi(n), so by definition d * e = 1. If so, m = (c^e)^d mod n = c^(ed) mod n = c. p and q are kept secret because they can be used to compute phi(n), which in turn lets us compute d. That’s it! A question that might arise is “Didn’t we learn an algorithm in school for computing the prime factors of any number? Doesn’t this mean we can find p and q given n?”. The answer is yes, but the naïve algorithm (divide by prime numbers until you get to a prime) is only pseudopolynomial in the input number, and not polynomial. A pseudopolynomial algorithm is dependent on the numeric value of the number, but not in its number of bits. So if you use a pseudopolynomial algorithm for factoring n, you’ll have to go through the order of 2^2048 numbers. An important note: The algorithm described above is called textbook RSA, and it is vulnerable to many attacks (for example, it is deterministic, so ciphertexts can be distinguished). In real RSA implementations, we also apply PKCS#1 padding, which pads the message with extra data and randomness. In step 1, we need to generate two large random prime numbers, but how can we do that? Obviously trial division won’t work when working with numbers of such size.

Generating Large Prime Numbers

According to the Prime Number Theorem, the n-th prime number p_n satisfies p_n ~ n log(n). This means that prime numbers are quite common, and so given a fast primality test, we can find primes efficiently by generating random numbers until we find a prime. The most common primality tests are probabilistic: they trade off some accuracy for efficiency. We will talk about the two very common primality tests: The Fermat test, and the Miller-Rabin test.

The Fermat Test

Fermat’s Little Theorem states that if p is prime, then for any a < p, we have a^(p - 1) = 1 (mod p). This gives us a fast method to check for primality: Just generate a random a < p, and check whether a^(p - 1) = 1 (mod p). If the equality is satisfied, we say that p is probably prime, and otherwise, p is composite. Here is the algorithm implemented in Rust:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

use num_bigint::{BigUint, RandBigInt};

/// Fermat's primality test

/// If n is prime, then for any a we have a^{n - 1} = 1 (mod n)

/// We pick a random a \in [1, .., n-1], and see whether a^{n - 1} = 1 (mod n)

/// If not, then n is composite

/// This test can fail, for example for n = 561

fn fermat_test(n: &BigUint) -> bool {

let a = rand::thread_rng().gen_biguint_range(&BigUint::from(1 as usize), &(n - 1u64));

let modpow_res = a.modpow(&(n.clone() - 1 as usize), n);

if modpow_res == BigUint::from(1 as usize) {

true

} else {

false

}

}

Why do we say that p is only probably prime and not prime? There exist numbers (infinitely many, actually), that can bypass the Fermat test. These numbers are called Carmichael numbers, and have many uses in Number Theory

The Miller-Rabin Test

The Miller-Rabin Test uses a stronger condition to check for primality: If n is a prime, then it has to satisfy 1 and 2 for all a < n:

- a^d = 1 (mod n)

- a^(2^r d) = -1 (mod n) for all 0 <= r < s Where n - 1 = 2^s * d. This is based on Fermat’s little theorem, and the fact that if n is prime, then the only square roots of 1 modulo n are 1 and -1 (this is not true in general; for example if n = 4, then 3 is also a square root of 1: 3^2 = 9 mod 4 = 1). To make the test more accurate, we repeat it for different values of a. Here is my implementation in Rust:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

/// Factor n into the form n = 2^{s} * d, where d is odd

/// Used in Rabin-Miller

fn factor(n: &BigUint) -> (BigUint, BigUint) {

let mut s: BigUint = BigUint::from(0u64);

let mut d = n.clone();

// While d is even, we can keep dividing it by 2

while &d % BigUint::from(2u64) == BigUint::from(0u64) {

// Amt. of 2's in factorization increased by 1

s += BigUint::from(1u64);

d /= BigUint::from(2u64);

}

(s, d)

}

/// The Miller-Rabin primality test

/// We know that n is prime if and only if the solutions of x^2 = 1 (mod n) are x = plus minus 1

/// So we can check whether a^2 = 1 (mod n) for random a, k times.

fn miller_rabin_test(n: &BigUint, k: usize) -> bool {

if n % (2 as usize) == BigUint::from(0u64) {

return false;

}

// Factor n-1 = 2^s * d

let (s, d) = factor(&(n - BigUint::from(1 as usize)));

// Try k different values of a

for _ in 0..k {

let a = thread_rng().gen_biguint_range(&BigUint::from(2u64), &(n - 2u64));

// Calculate x = a^d mod n

let mut x = a.modpow(&d, &n);

for _ in num_iter::range(BigUint::from(0u64), s.clone()) {

// Square x

let y = x.modpow(&BigUint::from(2u64), &n);

// We found a nontrivial root

if y == BigUint::from(1u64) && x != BigUint::from(1u64) && x != BigUint::from(n - 1u64) {

return false;

}

x = y;

}

// Fermat test: at this point x = a^{n - 1} mod n

if x != BigUint::from(1u64) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

Now that we have a way to generate prime numbers, we can implement RSA:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

const RSA_EXP: u64 = 65537u64;

const N_SIZE: usize = 256;

/// RSA Public Key

pub struct PublicKey {

/// Exponent

pub e: BigUint,

/// n = p*q

pub n: BigUint,

}

/// RSA Private Key

pub struct PrivateKey {

/// First prime factor: p

p: BigUint,

/// Second prime factor: q

q: BigUint,

/// d - multiplicative inverse of e mod n

d: BigUint,

/// phi(n) - (p - 1)(q - 1) - euler's totient of n

phi_n: BigUint,

}

/// An RSA keypair

pub struct Keypair {

pub public: PublicKey,

pub private: PrivateKey,

}

/// Generate a random prime with specified number of bits

pub fn gen_prime(bits: u64) -> BigUint {

// Chacha20 is a cryptographically secure PRNG (CSPRNG)

// Using regular PRNGs in crypto applications is a recipe for disaster :)

let mut rng = ChaCha20Rng::from_entropy();

// Primes are pretty common: The prime-counting function (number of primes smaller than some real number x)

// is approximately x / log x, which means that we have p_n ~ n * log(n), where p_n is the n-th -prime

// Therefore, the method we use to generate prime numbers is to generate random numbers with the specified number of bits

// until we hit a prime number.

loop {

// p and q are each half of the size of n

let mut bytes = [0u8; N_SIZE / 2];

rng.fill_bytes(&mut bytes);

let candidate = BigUint::from_bytes_be(&bytes);

if miller_rabin_test(&candidate, 12) {

return candidate;

}

}

}

impl Keypair {

// p and q can be provided if we have a predefined p and q,

/// Generate a new Keypair

pub fn new(p: Option<BigUint>, q: Option<BigUint>) -> Keypair {

let p = if let Some(p) = p { p } else { gen_prime(1024) };

let q = if let Some(q) = q { q } else { gen_prime(1024) };

let e = BigUint::from(RSA_EXP);

let n = &p * &q;

let phi_n = (&p - 1u64) * (&q - 1u64);

let d = e.modinv(&phi_n).unwrap();

let public = PublicKey { e, n };

let private = PrivateKey { p, q, d, phi_n };

Keypair { public, private }

}

/// Encrypt a message under the public key

fn encrypt(&self, m: &BigUint) -> BigUint {

m.modpow(&self.public.e, &self.public.n)

}

/// Validate a signature on a message

fn validate(&self, m: &BigUint, s: &BigUint) -> bool {

s.modpow(&self.public.e, &self.public.n) == *m

}

/// Decrypt a message under this private key

fn decrypt(&self, c: &BigUint) -> BigUint {

c.modpow(&self.private.d, &self.public.n)

}

/// Sign a message using the private key

pub fn sign(&self, m: &BigUint) -> BigUint {

m.modpow(&self.private.d, &self.public.n)

}

}

AES

As mentioned before, to encrypt the actual messages we’re going to use AES. AES stands for Advanced Encryption Standard, and was developed in 1998 by two Belgian cryptographers: Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen. In 1997, NIST started a competition for selecting a new Advanced Encryption Standard to replace the previous standard, DES. The competition lasted 3 years, and in the end Rijndael (the original name of what’s known today as AES) won the competition. AES is a block cipher: it operates on blocks of data instead of bit-by-bit (ciphers that operate bit-by-bit are called stream ciphers). The block size in AES is 128-bit (16 bytes) Block ciphers consist of rounds: each round is a small sequence of operations that is weak on its own but strong in number. Each round has a round key that determines how the round will behave. The round keys are derived from the main symmetric key K using an algorithm called the key schedule. The possible key sizes for AES are 128-bits, 192-bits, and 256-bits. The choice of key size dictates the amount of rounds performed:

- 128-bit corresponds to 10 rounds

- 192-bit to 12 rounds

- and 256-bit to 14 rounds Each round is characterized by a state. The state is a 4x4 array, which in the first round is set to the input block. The state of the final round is the resulting ciphertext block.

_Round_Function.png) In each round, we perform the following operations in the order they are listed:

In each round, we perform the following operations in the order they are listed: - ByteSub: Apply an S-box (Substitution box) to the current state. The S-box is a lookup table that replaces bytes with other bytes (for example replace 0x37 with 0xf3, replace 0x55 with 0xa8 etc.)

- ShiftRows: This step cyclically shifts the rows in the state. The second row is shifted left by 1, the third is shifted left by 2, and the fourth is shifted left by 3. The first row is left unchanged

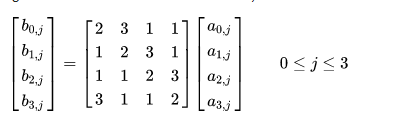

- MixColumns: Each columns is transformed using a linear transformation of the corresponding columns in the original state:

- AddRoundKey: The round key of the current round is added to the state using bitwise XOR. To use AES, we need to define the mode of operation. Some common modes are:

- ECB (Electronic CodeBook): This is the simplest mode - The message is divided into blocks, and all blocks are encrypted separately. The problem with this mode is that a small change in the input doesn’t correspond to a large change in the output (this property is called diffusion). ECB Also fails to hide data patterns (Identical plaintext blocks are encrypted into identical ciphertext blocks). The most common example is encrypting an image of Tux, the mascot of Linux using AES-ECB:

The result is:

The result is:  For a practical example of how we can find out the plaintext from the ciphertext when ECB is used, check out this cryptopals challenge: https://cryptopals.com/sets/2/challenges/12 Although the colors are changed, the overall pattern can still be seen.

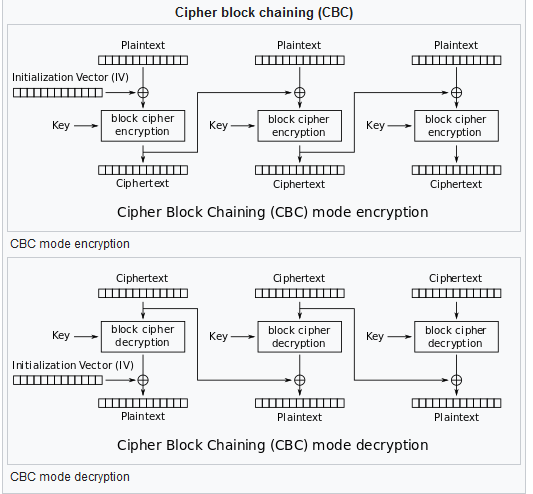

For a practical example of how we can find out the plaintext from the ciphertext when ECB is used, check out this cryptopals challenge: https://cryptopals.com/sets/2/challenges/12 Although the colors are changed, the overall pattern can still be seen. - CBC (Cipher Block Chaining): In this mode, every ciphertext block is XORed with the previous block. The first block is XORed with a block called the IV (initialization vector). The following figure shows encryption and decryption is CBC mode:

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation - CBC adds more diffusion than ECB, so it’s better to use In the chat, we will use CBC mode with a constant IV (in general the IV should be random and transmitted with the key, but I didn’t want to make it more complicated). To do this, I used the aes crate. This crate only provides the low-level AES operations (i.e. encrypting/decrypting a single block), so I implemented CBC on top of it: (note that AES requires the 16-byte blocks, so we need to pad the message)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

/// Encrypt AES in CBC mode with a constant IV

fn aes_cbc_encrypt(m: &mut [u8], cipher: &Aes128) -> Vec<[u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE]> {

// Calculate the number of padding bytes

let bytes_padding = if m.len() % AES_BLOCK_SIZE != 0 {

AES_BLOCK_SIZE - (m.len() % AES_BLOCK_SIZE)

} else {

0

};

// Pad the message using PKCS#7 Padding

let mut m_padded = m.to_owned();

m_padded.append(&mut [bytes_padding.try_into().unwrap()].repeat(bytes_padding));

// Split the plaintext into blocks, each of size 16 bytes

let mut plaintext_blocks = m_padded.chunks_exact(AES_BLOCK_SIZE);

// Construct the first ciphertext block, which we get by XORing the first plaintext block with the IV and then encrypting

let iv = b"YELLOW SUBMARINE";

let mut ciphertext_blocks: Vec<[u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE]> = vec![];

let first_block_slice = plaintext_blocks.next().unwrap();

// XOR with the IV

let first_block_vec: Vec<u8> = first_block_slice

.iter()

.zip(iv.iter())

.map(|(x, y)| x ^ y)

.collect();

let first_block: [u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE] = first_block_vec.try_into().unwrap();

let mut first_block_arr = GenericArray::from(first_block);

cipher.encrypt_block(&mut first_block_arr);

// Push it to the list of blocks

ciphertext_blocks.push(first_block_arr.into());

// Iterate over every plaintext block

for block in plaintext_blocks {

// XOR with the last ciphertext block

let last_c_block = ciphertext_blocks.last().unwrap();

let block_xored_vec: Vec<u8> = block

.iter()

.zip(last_c_block.iter())

.map(|(x, y)| x ^ y)

.collect();

let xored_block: [u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE] = block_xored_vec.try_into().unwrap();

// Convert to a GenericArray and encrypt

let mut xored_block_arr = GenericArray::from(xored_block);

cipher.encrypt_block(&mut xored_block_arr);

// Push to the list of ciphertext blocks

ciphertext_blocks.push(xored_block_arr.into());

}

ciphertext_blocks

}

/// Decrypt AES in CBC moed with a constant IV

fn aes_cbc_decrypt(m: &mut [u8], cipher: &Aes128) -> Vec<[u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE]> {

// These are the blocks we XOR each decrypted cipher block with

let mut xor_with = vec![*b"YELLOW SUBMARINE"];

// Split the ciphertext into blocks

let ciphertext_blocks: Vec<[u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE]> = m

.chunks_exact(AES_BLOCK_SIZE)

.map(|chunk| chunk.try_into().unwrap())

.collect();

xor_with.append(&mut ciphertext_blocks.clone());

// The first ciphertext block is XORed with the IV, the second is XORed with the

// First ciphertext block, etc. so we need to reverse the xor_with vector

xor_with.reverse();

// Plaintext blocks

let mut plaintext_blocks = vec![];

for block in ciphertext_blocks {

let to_xor = xor_with.pop().unwrap();

let mut block_arr = GenericArray::from(block);

// Decrypt

cipher.decrypt_block(&mut block_arr);

// XOR

let plain_block_vec: Vec<u8> = to_xor

.iter()

.zip(block_arr.iter())

.map(|(x, y)| x ^ y)

.collect();

let plain_block: [u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE] = plain_block_vec.try_into().unwrap();

plaintext_blocks.push(plain_block);

}

// Number of bytes of padding

let last_char = plaintext_blocks.last().unwrap()[AES_BLOCK_SIZE - 1];

// If the message is padded

if 0 < last_char && last_char < AES_BLOCK_SIZE as u8 {

let mut last_block = plaintext_blocks.pop().unwrap();

// Change all padding bytes to 0

for i in AES_BLOCK_SIZE as u8 - last_char..AES_BLOCK_SIZE as u8 {

last_block[i as usize] = 0;

}

plaintext_blocks.push(last_block);

}

plaintext_blocks

}

Putting It All Together

Now, let’s put it all together to create the handshake:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

pub struct Peer {

keypair: Keypair,

pub cert: Option<Certificate>,

pub stream: Option<TcpStream>,

pub cipher: Option<Aes128>, // The symmetric key

}

impl Peer {

...

/// Connect to the server, and perform the handshake

pub async fn connect(

&mut self,

host: &String,

port: u16,

ttp_host: &String,

ttp_port: u16,

) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

// Connect to the server

let mut stream = TcpStream::connect(format!("{}:{}", host, port)).await?;

// Connect to the TTP

let mut ttp_stream = TcpStream::connect(format!("{}:{}", ttp_host, ttp_port)).await?;

// Ask for the server's certificate

let mut cert_req = Message::new(MessageOpcode::HandshakeStart, vec![]);

stream.send_message(&mut cert_req).await?;

// We expect this to be the certificate from the server

let response = stream.receive_message().await?;

// Parse it into the actual certificate

let server_cert = Certificate::from_message(response).unwrap();

// Validate the certificate against the TTP

let is_cert_valid = server_cert.validate_certificate(&mut ttp_stream).await?;

// Close the TTP stream

ttp_stream.shutdown().await?;

// If the signature is not valid, exit

if !is_cert_valid {

stream

.send_message(&mut Message {

op: MessageOpcode::CertificateRejected,

payload: vec![],

})

.await?;

stream.shutdown().await?;

return Err(io::Error::other("Certificate is not valid"));

}

println!("Server\'s certificate is valid");

// Otherwise, send a message to the server

// To indicate that its certificate is valid

// And we can continue to the next part of the handshake

stream

.send_message(&mut Message {

op: MessageOpcode::CertificateAccepted,

payload: vec![],

})

.await?;

// Send the client's certificate to the server

// We expect this to be a request for our certificate

let request = stream.receive_message().await?;

// Respond to it with our cert

self.cert

.as_mut()

.unwrap()

.display_cert(request, &mut stream)

.await?;

// Check if the server accepted our certificate

let server_resp = stream.receive_message().await?;

if server_resp.op != MessageOpcode::CertificateAccepted {

stream.shutdown().await?;

ttp_stream.shutdown().await?;

return Err(io::Error::other("Handshake error"));

}

// At this point, we know the server's cert, and the server knows our cert.

// The server is supposed to send a message containing

// The symmetric key (bytes 0-15), and the IV for CBC (bytes 16-31)

let symmetric_key_msg = stream.receive_message().await?;

// The key we got is encrypted under our public key, so we need to decrypt it

let encrypted_symmetric_key = symmetric_key_msg.payload;

let symmetric_key = self

.keypair

.private

.decrypt(&BigUint::from_bytes_be(&encrypted_symmetric_key));

// Convert it into a GenericArray, to create a cipher

let symmetric_key_bytes: [u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE] =

symmetric_key.to_bytes_be().try_into().unwrap();

let symmetric_key_arr = GenericArray::from(symmetric_key_bytes);

// Create a cipher from the symmetric key

let cipher = Aes128::new(&symmetric_key_arr);

// We now have a stream with the server, and a cipher under which to encrypt & decrypt messages

self.stream = Some(stream);

self.cipher = Some(cipher);

Ok(())

}

/// Listen for another peer

pub async fn listen(

&mut self,

host: &String,

port: u16,

ttp_host: &String,

ttp_port: u16,

) -> Result<(), io::Error> {

// Listen for clients

let listener = TcpListener::bind(format!("{}:{}", host, port)).await?;

// Wait for a client

let (mut stream, _) = listener.accept().await?;

// Connect to the TTP

let mut ttp_stream = TcpStream::connect(format!("{}:{}", ttp_host, ttp_port)).await?;

// We expect this to be a request for our certificate

let request = stream.receive_message().await?;

// Respond to it with our cert

self.cert

.as_mut()

.unwrap()

.display_cert(request, &mut stream)

.await?;

// The client's response

let client_resp = stream.receive_message().await?;

// If the client didn't accept our cert, some error happened

if client_resp.op != MessageOpcode::CertificateAccepted {

stream.shutdown().await?;

ttp_stream.shutdown().await?;

return Err(io::Error::other("Handshake error"));

}

// Ask for the client's certificate

let mut cert_req = Message::new(MessageOpcode::HandshakeStart, vec![]);

stream.send_message(&mut cert_req).await?;

// The certificate of the client in bytes

let response = stream.receive_message().await?;

// Parse it into the actual certificate

let client_cert = Certificate::from_message(response).unwrap();

// Validate the certificate against the TTP

let is_cert_valid = client_cert.validate_certificate(&mut ttp_stream).await?;

// Close the TTP stream

ttp_stream.shutdown().await?;

// If the cert is not valid, exit

if !is_cert_valid {

// Indicate to the client that its cert is not valid

stream

.send_message(&mut Message {

op: MessageOpcode::CertificateRejected,

payload: vec![],

})

.await?;

stream.shutdown().await?;

return Err(io::Error::other("Certificate is not valid"));

}

// Otherwise, tell the client that its cert is valid

stream

.send_message(&mut Message {

op: MessageOpcode::CertificateAccepted,

payload: vec![],

})

.await?;

// At this point, we know the client's cert and vice versa

println!("Client\'s certificate is valid");

// Generate a symmetric key

let mut rng = ChaCha20Rng::from_entropy();

let mut key = [0u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE];

rng.fill_bytes(&mut key);

// Generate an IV

let mut iv = [0u8; AES_BLOCK_SIZE];

rng.fill_bytes(&mut iv);

// Encrypt the symmetric key under the client's public key

let client_public = client_cert.public;

let encrypted_key = client_public.encrypt(&BigUint::from_bytes_be(&key));

// Send it to the client

let mut msg = Message {

op: MessageOpcode::SymmetricKey,

payload: encrypted_key.to_bytes_be(),

};

stream.send_message(&mut msg).await?;

self.stream = Some(stream);

// Create a GenericArray of the key

let symmetric_key_arr = GenericArray::from(key);

// Create a cipher to use to encrypt/decrypt messages

let cipher = Aes128::new(&symmetric_key_arr);

self.cipher = Some(cipher);

Ok(())

}

...

}

This is exactly what we saw in the handshake figure:

- The client asks the server for its certificate

- The server responds with its certificate

- The client validates the certificate against the TTP, and tells the server of the result

- Same thing in the other direction (server asks for the client’s certificate, etc.)

- The server encrypts the symmetric key using the client’s public key, and sends it over the network

- The client and the server now have a shared symmetric key, which they use to encrypt messages Let’s test it:

Now, the message is encrypted!

Now, the message is encrypted!Summary

This was a very fun, difficult, and interesting project to work on, and I feel like I learned a lot both about Rust and Crypto from doing this. If you found any mistakes in the post, let me know :)

As always, thanks for reading❤️!!!!!!! Yoray :)